For people of colour, Britain’s colonial past is alive in our present

“When so much of your place in this world has already been decided by events of the past, it’s not long before you begin to question how in control you are of your future,” writes columnist Inaya Mohmood

It’s so easy for people to say that the past is the past and that we should move on and live solely in the present. For people of colour like myself, this is easier said than done. So many aspects of our identities have been and continue to be constructed by the past. British history, but more specifically its history as a colonising and imperialist power, continues to shape the interactions we have and witness. When so much of your place in this world has already been decided by events of the past, it’s not long before you begin to question how in control you are of your future.

Examples of the continuing effects of colonialism on the everyday lives of people of colour aren’t always as obvious as people using racist slurs or openly discriminating against us based on our skin colour. Instead there are much more subtle examples of interactions where race isn’t explicitly acknowledged but the power dynamic between white people and people of colour is still firmly in place.

I still feel very deeply the suffering of my ancestors and I often feel helpless, since I obviously can’t undo what’s happened in the past

An example of this dates back to a couple of years ago, when I was at my grandparents’ house. They had called the plumber in and my grandfather, who would’ve been around 70 at this point, kept referring to the young white man as ‘sir.’ Perhaps to some people this means nothing and is just an example of his impeccable manners. But I know that in some way my grandfather, a man whose parents lived through the British colonisation of the Indian subcontinent and who was himself born during the time of Partition, has somehow internalised the colonial ideologies of the past. They had instilled in him the racial hierarchies of colonialism, and for that reason he believed that in this situation he had a duty to display respect. Whether conscious or not, the power dynamics of the past were affecting the interactions he was having today.

The remnants of the power dynamics instilled by colonialism have also meant that there’s this universal idea that people of colour have to always be more accommodating during our interactions with white people. There are a lot of everyday examples of this: for instance, when walking on the same pavement, people of colour are expected to move aside to let white people pass. It’s not as explicit as ‘There comes a white person. Now we have to move.’ It’s instead a subconscious reaction to internalised racial power dynamics that have existed unchallenged in British society for decades.

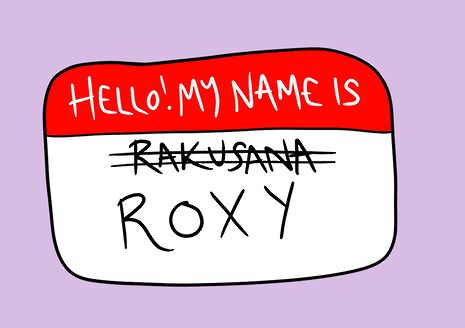

The same expectation for us to be accommodating is seen when people of colour are asked to make their names easier to pronounce or instead to adopt a ‘white name’. Take my mother for example. Her birth name is Rakusana but during her entire adult life she’s been called ‘Roxy.’ It’s not a difficult name to pronounce, but again the historically unequal balance of power between people of colour and white people has meant that my mother felt obliged to accommodate British society’s cultural illiteracy and go by a name that her parents did not choose and also has zero religious or cultural significance for her.

Beauty standards are another aspect of life that has once again been twisted to exclude people of colour and our own racial features. Small noses are preferred to big ones, straight hair over curly hair, and of course light skin over dark skin. The beauty industry is so Eurocentric that it feeds into the colonial mind set of racial hierarchies and physical differences as determinants of an individual’s worth. I’ve spent so much of my life feeling insecure about the features that I have inherited as a Pakistani woman, that I never questioned who set these ‘standards’ in the first place.

Maybe I’m wrong for spending so much time thinking about events that happened decades ago, and maybe people are right when they say that I’d be so much happier if I ‘got over it’ and ‘moved on.’ But I still feel very deeply the suffering of my ancestors during times like Partition, and I often feel helpless, since I obviously can’t undo what’s happened in the past. We live in a society that refuses to acknowledge the mistakes of the past, and would rather it be kept as a secret shame, never to be spoken about. I’d like to live in a society that recognises how its colonial history continues to shape the experiences of people of colour today, a society that actively works to undo some of these imbalanced power dynamics. A society where my grandfather recognises that, at the age of 70, and having lived through Partition and worked in Britain for decades, simultaneously providing for his family both here and in Pakistan, it is him who deserves to be called ‘sir.’

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026