Through death, breathe life

tan ning-sang explores the complexities of mental health, academic attainment and recovery through floral parallels

Content note: this article contains detailed mention of severe mental health issues, abuse, paralysis and psychotic episodes

Having just arrived back to Cambridge from Hong Kong, I walked into Mainsbury’s on a mission – equipped with shopping list in hand – to achieve that arduous student task of feeding oneself. Beyond being welcomed back by the familiar Sains bustle and pre-term “How was your break?” banter, I found myself distracted by bright red stickers on bouquets of alstroemeria reading “2 stems free!”

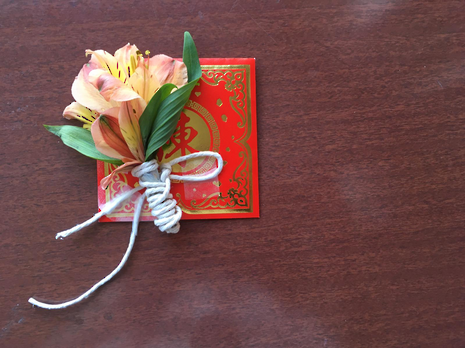

I love alstroemeria. Not only because they’re economically efficient, lasting several weeks, but because they were the flowers that my best friend and I used to leave at each other’s door on stressful weeks; they were the flowers that my mother purchased ahead of the new year. For me, alstroemeria carry memory, carry stories. And this year, it being the first that I live in a home away from the one I was born and raised in, I want to continue investing memories and stories into alstroemeria. Having just decorated our kitchen with red paper lanterns, I picked up a yellow-orangeish bouquet with dark red tips ahead of the Lunar New Year.

Returning home, I found a small vase, but accidentally cut the stems too short. Instead of finding a different vase or arrangement, I just stuffed as many stems as I could into that vase. But after several days, although all the flowers bloomed beautifully, there were a few drooping flowerheads. Upon closer inspection, I realised that the stems were malnourished and therefore unable to hold the weight of the flowerhead. Spindly, flimsy, discolored, the stems paled in comparison to the beauty they supported.

“Tripos’ stringent form of exam assessment is that broken system, a ‘stem’ failing to supply my ‘flower’ of intellectual and creative potential”

Examining those drooping flowerheads, I was momentarily confused about how to proceed. An unrelentingly neoliberal maximalist voice began coaxing me in a forget-me-not whisper: “Look, the flowers are still beautiful. They’re vibrant, full of life! If you cut them now, you won’t receive your money’s worth.” At the same time, another, bolder voice assured me of what I already intuitively knew: that the only way to save the bouquet was to cut off the flowerhead and stem.

At that moment, my mind turned to a conversation with a family friend from some years ago. This friend is the principal at one of the best primary schools in Hong Kong, which unlike other schools of the concrete jungle, operates a community rooftop garden maintained by students, staff, parents, and local farmers. I remember him telling me, “All the secrets in life are contained within the DNA of soil.” We stroll through endless rows of corn reaching for the stars. “At first, all you see are containers with dirt. But depending on the particular type of soil, the particular size of container, the particular angle at which the container receives light – all these factors determine how many of what type of seed should be planted in each container.” We stop in front of a malnourished stalk of corn. “I planted this,” he remarks, “intentionally, to remind students and parents that a living thing’s ability to thrive depends on external factors that must be considered when measuring that thing’s growth or success. A plant will try to grow regardless of its external environment. In a competitive city like Hong Kong, gardening therefore teaches children and parents that life is not only about achieving goals; it is also about cultivating the correct external environment for a child’s growth potential.”

My attention is brought back to the drooping flower, as I more clearly articulate my mistake to myself; that putting too many stems into one vase is the same problem as putting too many seeds into one container of soil: too much of a thing, when placed in too-close proximity to other things, leads to suffocation, unnecessary competition, toxicity, and ultimately death. It is exactly what happened during Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, during which increasingly absurd quotas set by the Communist Party led to peasants planting too many seeds in each lot, which became one of the causes of the widespread famine, responsible for the deaths of millions of innocents.

But it also made me think of the absurdly intense Cambridge terms, during which we all stuff ourselves silly with tasks and responsibilities. To the point where we drive ourselves into the ground, not understanding why we can’t get up when we’ve done everything that everyone taught us would lead to success. To the point where we drive ourselves into addiction and abuse – with alcohol, social media, shopping, sex, work, relationships – lying to ourselves as friends caught up in the same lies affirm us that such toxic habits are appropriate coping mechanisms. To the point where we no longer recognise ourselves, when we are unwittingly dispossessed of a self.

As someone who received positive academic feedback while experiencing severe mental health difficulties, I was particularly drawn to the observation that it was the stem and not the flower that was discolored, dysfunctional; that it was the support system that was supposed to nourish the flower, rather than the flower itself, that was clearly disfigured. In relation to my experience of last year’s exam term – when I had crippling depression and social anxiety, continuous insomnia and indigestion, various forms of paralysis, even psychotic episodes that rendered me literally unable to study for weeks – to me, Tripos’s stringent form of exam assessment is that broken system, a ‘stem’ failing to supply my ‘flower’ of intellectual and creative potential with the right nutrients to thrive. Yet, in miraculously scraping a First, I felt everyone’s gaze fixate on that supposedly bright flower of achievement, without any recompense to the disintegrating stem attached to it.

“I no longer want any part of such a narrow measurement of humanity.”

Because of that First, I have been given inconclusive diagnoses by psychiatrists and clinical psychologists regarding my learning difficulties, suggesting that because I continually perform well in my academics, I should not be given clinical ADHD treatment. Because of that First, my decision to change course and intended profession from Law to Theology was severely questioned because “you’re so good at Law,” forgetting that it was precisely the narrow nature of that academic discipline which triggered violent psychotic episodes. Because of that First, my decision to take time off was also severely questioned because “you did it before, you did so well, you can do it again,” forgetting how literally paralyzing and traumatizing academic work became for me. For whatever reason that our society privileges achievement in the form of two-digit numbers or single-lettered alphabets printed on pristine pieces of paper, I no longer want any part of such a narrow measurement of humanity. It is a broken, degrading system that diminishes entire, complex persons under a pretense of rigor. A*A*A. A*AA. AAA. AAB. Not good enough.

As a person of faith, I am reminded of the biblical metaphors concerning agriculture that I never understood or took seriously as someone raised in an urban metropolis. In particular, when Jesus says in John 15 that “every branch that bears fruit, [the Father] prunes it so that it may bear more fruit,” I never considered what is pruned to bear more fruit – that it is old fruit that gets cut off; beauty must die for beauty to survive. And if such fruit are not cut off, they will rot and infect the rest of the tree, bringing death and destruction to the whole. In my life, I am reminded that though the flowerhead of my academic ability appears to be in bloom, insofar as it’s attached to a toxic stem that measures a person’s worth strictly in terms of academic results – not even academic ability or potential – this flower will not only bring death to my nascent intellectual and creative potential, but to the whole bouquet of my being. It must be cut off.

“Taking time off has further enabled me to take a step back and realise that academic results are but one flower within a whole bouquet”

Taking time off has further enabled me to take a step back and realize that academic results are but one flower within a whole bouquet that’s increasingly growing, thriving, and being strengthened by non-neoliberal stems of love, community, and faith. These newer, ‘green’ stems consist of GPs, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists who take the symptoms of my manic and depressive episodes seriously; of therapists, counselors, advisors, and life coaches who listen carefully to my past and enable me to reach my fullest potential; of friends, cousins, aunties, and uncles who pick up my calls of panic at all hours of day, having chosen to be deeply committed to my wellbeing.

To continue with the metaphor, it is further understanding that there are various ways to deal with the fallen flower, once cut; the flowerhead is not completely devoid of value immediately upon separation. In this particular case, I taped the fallen flowers together and used them as ornamentation for a thank you card. Other times, I dry or press the flowers into books for memory and safekeeping. Far more often, I just throw them out. Life does not demand that we actively know which flowers need cutting off, which ones should be preserved, and which ones should get tossed out. In nature, such occurrences just happen, as the seasons come and go, year after year after year.

But what of our connection to ‘nature’, of our understanding of such basic rhythms in life? We live in a time in which we’ve forgotten how to listen, how to sit, how to speak, how to love, how to breathe, how to relax, how to see, how to be; where we turn to Marie Kondo to declutter our incessantly overflowing lives and illegal doses of Ritalin to momentarily enhance our weak muscles of concentration. Where is there space that is slow enough, open enough, in which we could collectively learn to hear again, to know our place in this world of flurry and flux? Is there a place to still hearts, to still minds, to know and remember beauty, love? A way to hear our own heartbeat, our own swan song?

“In the slowing down, in the learning to listen, I am finding a world open to my imagination, one that accepts and invites my fragmented being.”

I do not profess to know any secrets about the mysteries of life. All I know is that life demands to be lived, for us to be, to be free; that a necessary part of living is dying, and that indeed it is only through deaths of things and selves that true living, true freedom might chance an appearance.

In honor of the recently passed Mary Oliver, it seems apt to conclude with the ending lines of one of her most famous poems, Wild Geese:

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

Navigating a complex web of clinical diagnoses, cultural and personal trauma and abuse this past year has been incredibly difficult, to say the least. But I do think that I am slowly finding that place of rest, that place of being, my place in the family of things, within myself and in the world around me. In the slowing down, in the learning to listen, I am finding a world open to my imagination, one that accepts and invites my fragmented being. For no matter how difficult, no matter how lonely, I know that I am alive and living, free. And that is a beautiful thing.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026

News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 Features / Who gets to speak at the Cambridge Union?6 January 2026

Features / Who gets to speak at the Cambridge Union?6 January 2026