Invisibility or political rebellion: fashion in the GDR

In an interview with her mother, Fashion Editor Isabel Sebode questions the role of fashion in the socialist regime of the GDR – an investigation into political conformity or non-conformity through clothing.

The world on lockdown, supermarkets emptying and spreading fear – history is being written as we speak. But someone who has already lived through history and come out on the other side is my mother. Growing up in Dresden and Berlin, my mother Franziska lived in the GDR for the first 25 years of her life, making her a valuable witness of changing times and, albeit a cliché, one of the main reasons for my interest in fashion.

The German Democratic Republic was, unlike West Germany, a socialist state, influenced by the Soviet Union. Rather than embracing the capitalism of the West, East Germany operated under a centrally planned economy: state-owned businesses, minimised consumerism and limited availability of goods. As a result, fashion was not dominated by large corporations or independent designers but was primarily state-controlled, or sold by individuals.

Nowadays, aesthetics, self-expression and an ‘anything goes’ attitude define our clothing experience. However, Franziska identifies a fundamental difference in attitude that distinguishes life in the GDR from today. The GDR celebrated the “hard-working, dapper woman”, who would emphasise simplicity in style and focus her attention on “raising her children whilst working fulltime”, she says. Functionality was key, so was conformity. The socialist society valued productivity, community and similarity. “The classic picture would be of the Stasi-workers”, Franziska remembers distinctly, “who would wear beige trousers and a grey jacket. Inconspicuous to the point of invisibility.”

Yet, a forced focus on functionality does not equate with an total disregard for fashion. The popularity of magazines such as the ‘Sybille’ showed that women, in particular, were concerned with their appearance. Instead, the main problem was access. Being interested in fashion as well as having time to engage with it was one thing – actually gaining access to the clothing items often proved to be the real obstacle. Franziska defines three key conditions: “to identify yourself with the West, to have the money for the scarce West-clothing and to have the opportunities to actually buy it.“ Instead of free choice between various brands, in the socialist regime, only a limited variety of shops was available: “there were the controversial ‘Intershops‘ for people that had 'West-money' (either from relatives or the black-market) and then there were the ‘Exquisite-shops’. In these, luxury West-oriented fashion was sold for very high prices.”

Evidently, the desire for fashion in a time of need and restriction was primarily based on what consumers didn’t have. Instead of buying clothing according to what is popular at the moment, people yearned for variety in clothing, which was only available in the West or in pseudo-West stores. Alternatively, “if you were creative, you’d just sew yourself”.

Occasionally, this was what Franziska opted for to free herself from the limitations. In a country of conformity, clothing was not aimed at self-expression but subjugation. To escape the white blouse and red or blue scarf of the ‘young-pioneers’, one would try their best at fleeing into the world of the ‘other’ or attempt to recreate this world with textile, yarn and a sewing machine.

Franziska was aware of the implications of her behaviour: “Individualism was not wanted, as an individual style promotes autonomous thought. In this way, any deviation from the norm was critically examined.” Regardless, taking fashion into her own hands she attempted to recreate the things that remained scarce. Whether or not this was always successful didn’t matter: “the old would not be discarded, it would be reworked and used in a new way”. Evidently, sustainability has its origins in the society of need, rather than in that of excess and privilege. As a result, Franziska highlights two behaviours that were customary in the GDR: creativity and sustainability. Sounds ideal? Franziska laughs. “Nowadays everyone is commended when they make sustainable choices or deviate from fast fashion. But we didn’t have that choice!”

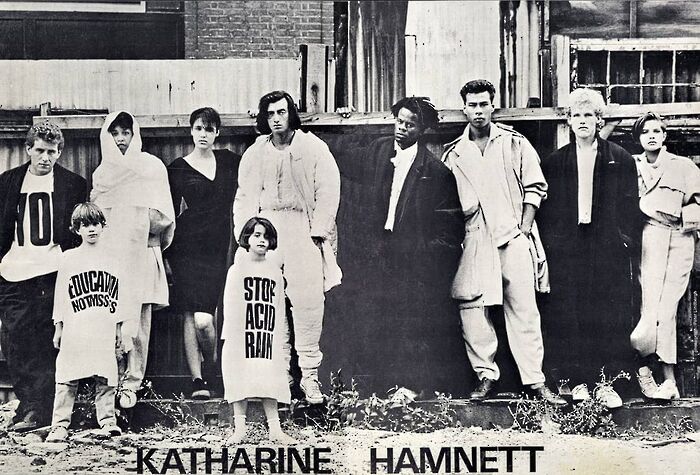

“We did not consciously decide to engage in a sustainable lifestyle. Instead many of us longed for the consumerist dream of the West.” Yet, in a socialist society “being chic with a sense of fashion was associated with decadence and a distance from the socio-political system”. Although politically questionable, this is what many people secretly wanted, for example in the form of the ‘blue-jeans’, a product of the West that is now a staple in everyone’s closet.

My mother remembers: “my father strictly forbade me to wear the ‘West-Jeans’, so on some days I used to wait in line for hours in front of the state-owned ‘youth fashion’ store, in case they sold jeans that day. Sometimes the queues in front of these stores were hundreds of meters long.” Like nowadays, people wanted that which they had the least, the things that were somewhat provocative, or communicated a political message. “One day, my mother asked a dressmaker to sew me a pair of jeans, to do me a favour. Yet, the result was not like real jeans and they looked rather ugly to me. I never wore them.” She smiles. Even in times of need and restriction, fashion was a form of self-expression and with that comes the liberty of deciding what to wear, and what not to.

Art, fashion, music – culture is unarguably the key influence on our national and individual identity. Fashion, in particular, offers individuals a private form of rebellion and expression, especially when one would rather distinguish oneself from the national identity than embrace it. Sitting down with my mother makes me think about her influence on me. I tell her how I remember cutting out a huge picture of red lipstick and sticking it on A4 white paper, pasting some stilettos next to it and a picture of Miranda Kerr. Franziska leans back and thinks about my grandmother. “My mother was never very close to her state.” She was a hairdresser in a privately-owned shop in Berlin, and came out of a creative and artistically engaged household with a classical education and a key interest in fashion. “Because she had contacts in West Germany, she would occasionally receive clothes from the West. From her, I learned to be aware of my outfits and appearance at all times. For myself, not for others”

She takes the last sip of her coffee and opens the German Vogue she has open in front of her. The GDR woman that works hard and cares for her family is still present in the person sitting in front of me, yet the world she lives in is detached, through time and change. Functionality has been replaced with provocation, expression and redundancy. Expressing ourselves through fashion is no longer a political feat but the norm, facilitated by availability, if not excess, of clothing. Sustainability and creativity are personal decisions to distinguish ourselves from fast-fashion and consumerism, rather than the only way to wear something that doesn’t force us into the grey-beige-blue box of a dwindling identity. “Have you seen the Vogue Interview with Isabel Marant?” she asks, and momentarily I see the young woman that would have queued for these magazines in front of my eyes.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025