Orlando Figes: The Memory of Revolutionary Russia

In the centenary year of the Russian Revolution, Josh Kimblin speaks to acclaimed historian Orlando Figes about the long shadow of 1917 and the regime it created

One cannot move for ‘revolutions’ these days. Everything from Trump, to Brexit, to the latest anti-ageing product is described in revolutionary terms. However, this verbal inflation is put into perspective when we consider the events in Russia in 1917.

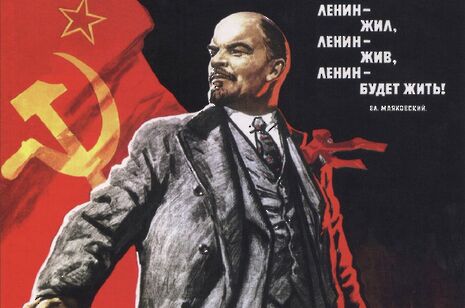

The Romanov dynasty, which had ruled over a sixth of the planet's surface for three centuries, lost power in February. By October, the Bolsheviks had seized it. Within 50 years of the establishment of Soviet power, a third of the world’s population lived under regimes modelled upon it. Yet, a century later, humanity’s greatest experiment in social engineering has been firmly consigned to the history books.

The revolutionary legacy lives on, though, shaping both international politics and the domestic Russian psyche. Few people know this better than Orlando Figes, Professor of History at Birkbeck and author of A People’s Tragedy – a definitive chronicle of revolutionary Russia.

For Figes, the tragedy of the Revolution lay not only its human cost but in Russia’s failure to realise a national democracy. This is a tragedy which has never ended: Freedom House, a pro-democracy think-tank, has categorised Russia as “Not Free” since 2005. So was there ever realistic hope for a democratic Russia?

“Yes,” Figes replies. “There was an opportunity after 1991, which was missed. To have been successful, it would have required a much more concerted effort to democratise institutions, reform school curricula and to encourage debate about history.”

“The problem with [that attempted debate] was that most Russians were uncomfortable with the collapse of the USSR. It focussed on all the blank-spots of history which they didn’t want to examine. Ordinary people didn’t feel comfortable speaking about the recent past.”

“The myth of 1917 is so powerful and so central to the idea of Russia’s statehood and its future, irrespective of its violent aftermath.”

Orlando Figes

Figes suggests that an unwillingness to confront the difficult aspects of Russia’s past was exacerbated by a more serious inability to place individual stories in a wider context. “Many people didn’t just suppress the memories of Stalin and Brezhnev. Rather, they didn’t have a conceptual apparatus to help them understand what had happened to their families.”

This “conceptual apparatus” is ‘collective memory’ – a term sociologists use to describe shared sets of information and experiences, which are passed down generations and inform our contemporary reactions to historical events.

“For collective memory to operate properly, as it does in free societies, you need a framework – a narrative of your society’s history,” Figes explains. “In Russia, that narrative has never been allowed to exist independently; collective memory has always been suppressed by Soviet ‘official memory’.”

“When I did the oral history project for The Whisperers, people would repeatedly say in a confused way: ‘This happened, and this happened.’ All terrible things. But they didn't understand why it happened. And they continued to advocate ideas taken from the ‘official memory’ of the event: that collectivisation was necessary; that Stalin’s Purges were essential for victory in the Second World War; or that Stalin was great, despite all.”

The terrible irony is that these ideas are contradictory. “People can quite easily accept that the Cheka killed between ten and twenty million people in the 1930s but [believe] that it was nonetheless doing a good thing defending society.” As a result, Figes argues, Russian families can tell individual tales of horror but continue to believe a state-endorsed narrative of terrible necessity.

Is there any chance of such a collective memory apparatus developing under Putin? I ask this half-expecting the answer: predictably, Figes declares there is none. Rather than address traumas, Putin has routinely tried to restore pride in Russia’s Soviet past. Indeed, he declared to the Russian Federal Assembly in 2005 that “the breakup of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century.”

This initiative commands broad support. Polls show some Russians harbour a nostalgic yearning for a mythic Soviet past: in a 2005 survey, 60% of respondents aged over 60 explicitly wanted the return of a ‘leader like Stalin’. Figes relates the findings of a TV series which asked an audience for opinions on historical issues: “uniformly, over 90% of the audience believed that collectivisation was necessary, even after they’d assimilated the fact that millions were killed.”

“Ukraine is another good example,” he suggests, pointing to Putin’s success in generating nationalist capital out of his annexation of Crimea. Once again, the public response to that revanchist manoeuvre was related to an issue of collective memory.

“The state’s ability to gain popular legitimacy through the use of violence is rooted in Russia’s inability to come to terms with her revolutionary legacy,” Figes explains. “The myth of 1917 is so powerful and so central to the idea of Russia’s statehood and its future, irrespective of its violent aftermath.”

Can Russia’s apparent penchant for strong, autocratic leaders – from the Tsars to Putin – also be explained in the same way?

“I certainly don’t think it can be explained in terms of the DNA of Russians, which is how it often gets explained,” Figes says quickly. “There isn’t even anything ingrained in Russia’s political culture, in terms of a love of monarchical power.”

“It’s about institutions. If you think about Russia’s history post-1991, where are the genuinely free institutions? Where are the institutions of civil society: the charities, the consumer societies, the trade unions, the political parties? They don’t exist. And that’s because, once again, people don’t have the institutional experience of those organisations. So, yes, it goes back to a memory issue. If a nation doesn’t have a historical culture of democratic institutions, then it is unlikely to manifest them successfully in the present.”

He suggests Eastern Europe, after its liberation from Soviet control, as a counter-example. “They [Eastern European states] had the Church; they had a memory of civic institutions which had regularly asserted themselves in resistance. They had trade unions – Solidarność in Poland, for example. They were also given the base of being anti-Russian; they could define themselves in opposition.” These institutions, Figes argues, helped Eastern European states develop more successful democracies after the Iron Curtain fell.

“We’re in a situation which has, if not revolutionary potential, then at least radicalising potential.”

We turn from the past to the present. A few months ago, I spoke to China Miéville – another historian of the Russian Revolution and Communist activist – who suggested that today’s febrile political climate offered “opportunities” for the left not dissimilar to those of pre-revolutionary Russia.

I put it to Figes that, much like 1917, we have a delegitimised centre ground, a collective discontent with an elite, and a strong movement in favour of social justice and wealth redistribution.

Figes’ reaction to these comparisons is predictable. “I don’t think we’re in a revolutionary situation. That’s stuff of nonsense,” he says flatly. “Those comparisons forget that we don’t have a world war going on; we haven’t had three years of mass slaughter and economic dislocation.”

“However,” he continues, “we’re in a situation which has, if not revolutionary potential, then at least radicalising potential, which is what we’re seeing operate politically. A really key change has occurred in the transmission of information. In a revolutionary situation, like 1917, the power of rumour and word is enormous; their equivalents of social media and fake news defined actions and political events. The rumours around Rasputin are a good example. It’s what people believe in a revolutionary situation that matters – not what’s true or not.”

“Today, the breakdown of trusted sources of information is a radicalising process, because when you get angry people, desperate people, frustrated people, who can be quickly mobilised to believe things – irrespective of the truth – and mobilised to act on those beliefs, that is a radicalising tendency.”

“That’s the force of action which we’ve seen in the Arab Spring and the recent election. Social media can be very effective in mobilising ‘revolutionary’ action. The state is now, vis-à-vis that societal organising power, much weaker.”

But has that change created a revolutionary situation? “Not in itself,” Figes believes. “Britain is not a revolutionary society and never really has been. What do the kids want? They want a job and security; they want the opportunity which their parents had, which is to own something. Those aren’t revolutionary ideas; they’re instinctively conservative.”

Read more: Neil MacGregor: History, Faith, and Dürer's Rhinoceros

For all the revolutionary rhetoric which pervades our current political discourse, our situation is less favourable towards insurrection than perhaps some would like.

The ghosts of 1917 may not be at rest, but they are unlikely to be resurrected here

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026