Lucy Worsley: a Janeite crusader?

Josh Kimblin meets the renowned historian to discuss the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death

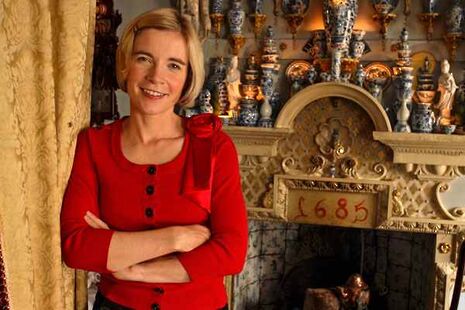

Lucy Worsley is Chief Curator at History Royal Palaces and a household name in BBC history broadcasting. When not looking after the Tower of London and Hampton Court (among others) or filming her latest series, she is a prolific author. She came to the Wimpole History Festival – an event organised by the Cambridge Literary Festival just outside Cambridge – to discuss her recent publications about Jane Austen and children’s books, in which she fictionalises the true stories of young girls in extraordinary historical situations. I met her to discuss Austen in the bicentenary year of the author’s death.

JK: Two hundred years after her death, Austen is at once very familiar – the bonnet, the cottages, the occasionally acerbic wit – but also very distant to modern audiences. What underpins our fascination with her?

Worsley: It’s partly the mystery element about her life. I’m always asked: “How did she die, then?” Nobody knows! So there is a wonderful ‘mystery adventure’ to undertake in working out who she was.

The other element is the fact that she can exist in so many ways in the popular imagination. That’s a function of the evidence about her life, which is so fragmentary that it can be read in different ways. In the same way, her books are true works of art because, like Shakespeare, you can read them in different ways. You can have multiple readings of the same text; like her work, Austen has a kaleidoscopic aspect to her biography.

JK: Having now examined her life – and especially the places where she lived – has your interpretation of the books changed?

Worsley: I read all of the books and then came to her life-story as sort of a seventh novel. That added to my enjoyment of what had come before because I discovered the echoes, parallels and shadows in her own life. It only functions like that up to a point, though. I don’t think she put her life into her work in a straightforward manner. In fact, she laughed at the critics who believed she had done that! She was far too clever to think that a novel worked simply by taking “Life” and writing it down.

JK: So she mocked those who failed to appreciate her own artistry?

Worsley: Oh yes! One of the great things about her is the way that she laughs routinely at stupid people: it’s not necessarily a likeable characteristic but an enjoyable one for a biographer. You become familiar with her sense of humour, which is often the most intimate part of an individual.

“I’m a signed, sealed and delivered Janeite.”

JK: Partly as a result of the intimacy readers feel with Austen, her position in today’s cultural life is quite exalted –

Worsley: Is it?

JK: Yes, I think it is. There are generations of schoolchildren, who read Pride and Prejudice for their GCSEs or equivalent, who immediately associate the words “novel” and “author” with Austen – or perhaps Brontë.

Worsley: True. That used to be a film: “Austen vs. Brontë”. Like “Monster vs. Predator”.

JK: But perhaps with more bonnets! Nevertheless, related to the comparatively high esteem in which Austen is held, your book suggests that you admire her. Do you?

Worsley: I love her! I’m a signed, sealed and delivered Janeite.

JK: So are you out to convert those who aren’t Janeites?

Worsley: Absolutely. I think that all historians have their prejudices and those who claim to be impartial are really just in denial. I feel it’s better to simply put them out on the table and say: “Deal with it; this is my side of the story.”

JK: And, I suppose, being prejudiced about the author of Pride and Prejudice is paradoxically forgivable.

Worsley: [Laughing] Yes, I would hope so!

“For romance to be truly romantic, it needs to work against something.”

JK: There is a stranger element to Austen, though, in that she’s become an icon for the conservative Alt-Right in America.

Worsley: Yes. [She pauses] I don’t really understand that – and yet, I do. You can read her as a profoundly conservative writer, who is interested in the good stewardship of an estate, who is against the nouveau riche. I suppose the rightful ordering of society is a valid concern.

JK: There is still a romanticism in Austen’s work – a buttoned-down, prim and proper romance, but a romance nonetheless.

Worsley: Certainly. And it’s all the more romantic for being prim and proper. For romance to be truly romantic, it needs to work against something: there must be constraints. If you can have unrestrained sex with whoever you like, then there’s no romance. In this case, social mores and money are the great constraints.

The interesting thing is that, although those constraints create the romance in Austen’s work, she was also subtly, minutely but devastatingly attacking them. She was part of that society but knew how rubbish it was – that women had to marry for money.

JK: Do you see that as a proto-feminist interpretation?

Worsley: Yes. Absolutely. I’m not alone in reading the works in that way: many other scholars are feminists and share that view. It was the Victorians who suggested the “Saint, Aunt Jane” image: Miss Marple-like, living in a country village, not really knowing what a good writer she was. It’s a deeply patronising image.

Neil Macgregor: History, Faith, and Dürer's Rhinoceros

JK: On the subject of female writers and writing for girls, what were your motives for writing your latest children’s books?

Worsley: It’s about making history accessible and fun. I got to where I am by reading historical children’s books: Jean Plaidy was my writer of choice when I was an eleven-year-old girl. I am very self-indulgently writing for my eleven-year-old self – whom I hope would be in the queue for book signings outside!

I like having young, female protagonists – and telling a good story. Stories are what makes history fun: it is basically a soap opera. Then they have to move onto analysis, judgement, and historiography – all the other tools in the tool box. But the reason we go on endlessly about Henry VIII and the Tudors is because they are entry-level: he gets people over the threshold in terms of engagement with history.

Judging by the length of the book queues snaking out of the signing-tent, it seems that Worsley has more than succeeded in her aim

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026