David Bailey CBE: ‘Is photography art? Of course it’s fucking art’

Elizabeth Howcroft talks to photographer, filmmaker and artist David Bailey

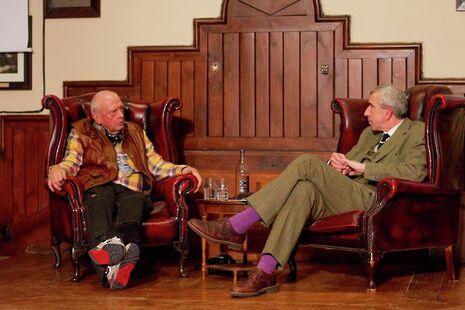

There’s something pleasing about watching a slideshow projection, in the Union’s main chamber, cover the old framed portraits of stern Union hacks with the bold, sexy and instantly-recognisable monochrome images of Mick Jagger, The Beatles, Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and Kate Moss. The 78-year-old photographer and filmmaker David Bailey sits on a platform in the middle, his sleeveless brown leather jacket not quite matching the Union’s armchairs, looks around the chamber, amused, and comments in his unmistakable Cockney accent: “it’s nice here, innit”.

Later I ask if him he minds the fact that interviewers inevitably question about his childhood, growing up in East London during the Blitz. “Whatever you start with, that’s what you have to live with for the rest of your life,” he says, shrugging it off. “That’s sort of the capital letter of your life, in a way.”

It is perhaps ironic that, for a photographer so central to the forward momentum of the world of fashion and celebrity, conversation seems to return so often to the themes of his childhood and past. Born in 1938, Bailey suffers from severe dyslexia and dyspraxia, as a result of which, he claims, he left school almost illiterate. He links this directly to his visual talents and explains that his mother thought he might become a commercial painter when he won a prize for a painting of Bambi. Instead, however, he became an assistant to the photographer John French until, in one of the most significant moves the institution would ever make, British Vogue gave Bailey his first contract. He was aged 21 and the year was 1960.

In Bailey’s 60s – and they really were Bailey’s 60s – the concept of the celebrity was at its most explosive and, as a fashion photographer, he found himself at the centre of this. Bailey dated Jean Shrimpton, photographed Andy Warhol and created the album art for the Rolling Stones. When he married Catherine Deneuve in 1965, Mick Jagger was his best man. During our interview, I struggle not to fall over the names he unashamedly drops. For example, an attempt to convey that he does more than take photos turns into: “I still make film – I made a film last week – I made a video for Valentino.” He’s nonchalant as he explains: “A punk rock and roll video, it’s quite good.”

“Is photography art? Of course it’s fucking art.”

If this is affectation, it’s pretty good. He forgets – or feigns to forget – Alice Cooper’s name, but remembers that the rockstar, whom Bailey photographed wearing nothing but a live snake, played a lot of golf. Returning to more recent times, he describes Katie Price as “kind of frightful” and admits to having called the Queen ‘girl’ (“yeah, but not on purpose”). But contrary to his reputation, I don’t see Bailey’s scathing wit stray into hostility – in fact, his manner seems at times almost Wildean, as he speaks in brilliantly-crafted epigrams. Regarding Diana Vreeland, the 1996 Editor-in-Chief of Vogue, for example, he accompanies his unforgiving impersonation of her with the remark: “She was clever, too. If we were talking about something she didn’t know about, she’d change the subject.”

More jaded than especially anti-establishment, Bailey is strangely dismissive of the sensational world of which he is part – the world which, from an outsider’s perspective, appears to have created him as much as he created it. I tell him that this is a world I’ve only experienced through the glossy pages of magazines and he laughs, unpatronisingly: “no, I don’t see anything like that. It’s just the world, it’s just part of the world.” In what I come to appreciate is typical Bailey, he takes the question away from fashion and into perhaps an under-represented area of his work: “I mean, remember I’m in touch with all the other things in the world as well. Did you see my book on the East End? – no,” he answers his own questions before I can, “it’s big, it was three volumes.” He often speaks of Vogue in terms of “selling frocks” and seems equally bored by his own art: “I don’t like photography. I’m not interested. I don’t like it when people say what kind of camera that is, like, ooh, I dunno.”

“I don’t like photography. I’m not interested. I don’t like it when people say what kind of camera that is, like, ooh, I dunno.”

Bailey is notoriously difficult to interview. He has a habit of rejecting whatever conclusions are suggested, almost as though out of principle, and his default answer is ‘no’. Yet for all his glamour, crudely disguised by a thick accent and a tendency towards the expletive, he doesn’t strike me as a diva. Not so much impatient as somewhere between baffled and amused, it occurs to me that he’d be more likely to stick around and give one-word answers than storm out of an uncomfortable interview in a rage. At the end of our interview he calls me a “sweet thing” and then asks me my age, which alters the tone of the compliment somewhat.

Bailey can’t quite shake off his bad-boy reputation with the same ease as he does journalists’ questions. The fashion world talks, a lot. Grace Coddington, the former model and now creative director of American Vogue writes in her memoir, Grace: “he had a harem of pretty girls available to him and a wildly promiscuous reputation. ‘David Bailey makes love daily’ was the famously racy saying of the day, which gave us all fair warning. And yet he was so skinny and undeniably attractive, even better-looking at the time than the Beatles.” Editor-in-chief of British Vogue, Alexandra Schulman, seems to have been somewhat less impressed, as she recently caused a stir by writing in her published diary of “David Bailey comparing himself to Picasso and then asking Vogue’s fashion director, Lucinda Chambers, why she hasn’t had Botox.”

The Picasso remark is interesting; Bailey often talks about art. He’ll refer to Picasso, Michelangelo and Caravaggio as though they are old friends he encountered somewhere between the Kray Twins and Freddie Mercury. After telling me “I never thought of myself as a photographer – it’s just something you do,” he adds, “I don’t mind. I could have carried on painting.”

It is when talking about painting that he is at his most charismatic. Somewhere between a rant about a film he once made and an anecdote about John Lennon, he answers a question that I certainly hadn’t asked: “Leonardo [Da Vinci] wrote a manifesto to all the poets ’cause they said painting can’t possibly be art because you need mechanical things, you need paint and pigment, and paintbrush and a canvas. And he said, ‘You poets are wrong, there can be poetry in painting.’ So it’s the same argument about photography – is photography art? Of course it’s fucking art.”

He regularly contradicts himself, yet still manages to impress me with his apparent authority and insight. “Painting isn’t art,” he tells me, and “anyone can be a fucking photographer. Easier to be a painter, I’ll show you, look,” – he grabs a leaflet off the table and scribbles me a drawing of a stick man in a top hat – “how quickly can you do that, and people think photography’s…” – he breaks off as he hands the doodle back to me. “Anyone can draw or paint or do anything!” he concludes triumphantly. I look at the picture and wish I had the gall to ask him to sign it.

“Meat robots,” he adds, as I find myself rapidly losing my faculty of speech. “I always thought we were meat robots, ever since I was able to think, in some kind of video game for aliens.”

If ‘meat robots’ is an apt image for the world of fashion, the idea of a ‘video game for aliens’ is even more evocative of the strange cosmos from which Bailey has descended. I recall that his major exhibition – at the National Portrait Gallery in London, the National Gallery in Edinburgh and Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan – was called ‘Stardust’, a name which stuck in my head as an impressionable teenager at the time.

Our interview ends just as he gets started on the sculptures he wants to start making. They’re going to be about Hitler killing a duck, which brings us back to where we started – with the boy who grew up during the Blitz with a vivid imagination. Bailey’s a genius and he’s mad as a hatter. But he’s not lost up in the clouds; he’s among the stars

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026