Mental health: it’s not all ‘in your head’

The binary opposition drawn between mental and physical health is harming productive conversations about mental illness, argues Martha Saunders

When I was very depressed one of the hardest things was explaining that I didn’t feel sad. My illness was poorly understood by even the most well-intentioned of friends and welfare staff; I was offered counselling, cups of tea, and kindness. When I missed deadlines or appointments any compassion I received was under the assumption I had been in too much of an emotional state to manage, as though a personal tragedy had occurred. In fact, my problems were significantly more physical; the fatigue and aching was so bad I could barely get out of bed, and my depressed brain was unable to hold the time of an appointment in my mind. Even tweets were swimming around on my phone like hieroglyphs, refusing to form coherent sentences. I couldn’t read 140 characters, let alone the dense academic texts on my reading list.

“Putting mental health in opposition to physical health explicitly implies mental illness is not a physical thing – that it isn’t really ‘real’”

I expected little more from an illness which is literally metonymic for ‘sad,’ but the proximity of mental illness rhetoric to the way in which we describe normal emotional states is symptomatic of a wider problem. We stubbornly reinforce the ‘physical’ versus ‘mental’ illness binary in spite of mounting evidence that it has no social or scientific legitimacy.

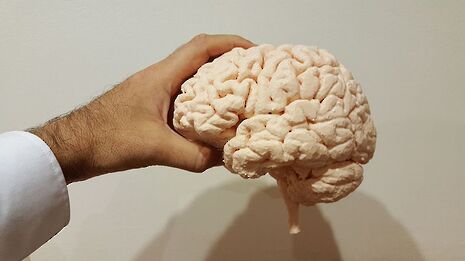

Putting mental health in opposition to physical health explicitly implies mental illness is not a physical thing – that it isn’t really ‘real.’ From depression and anxiety to personality disorders, tangible chemical dysfunctions in our brains which are just as biologically ‘real’ as tonsillitis or Parkinson’s are reduced to an abstract – seen as character defects, mental weaknesses or just very strong emotions.

Switching courses to Psychology transformed my ability to talk about my mental health. I learned that my memory problems, low attention span and exhaustion had been real, tangible, physical effects of depression caused by chemical imbalances in my brain. This effect is well documented – comedian Ruby Wax, who spent decades struggling with depression, wrote about how her Master’s in neuroscience at Oxford transformed her ability to manage her illness. In her book Sane New World she explains the workings of the brain and its neuroplasticity in an accessible format, lamenting the public’s appalling lack of knowledge about how our own minds work and condemning the mental-physical binary, asking: “why, when you have a mental disease, is it always considered an act of imagination? Why is it that every organ in your body can get sick, and you get sympathy, except the brain?”

Her accessible, frank insight into the science behind mental illness was applauded but drew criticism for insufficient focus on how individual traumatic or negative life experiences shape mental health. This is often the argument used to support the difference between mental and physical health. But this is unhelpful in multiple ways. Traumatic experiences don’t just make you feel sad, they shape your chemistry, especially in early childhood when your brain is still growing. Childhood trauma, for example, has a drastic long term impact on the levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) in the brain, flooding survivors’ bodies with stress and leaving them vulnerable to an array of mental illnesses. Recent studies in epigenetics suggest that these vulnerabilities can even be passed down to your children.

But associating mental health with bad experiences or emotions and physical health with biological accident is just as damaging for how we perceive physical health. The groundbreaking Adverse Childhood Experiences study found that children experiencing serious stressors such as abuse, neglect or parents with mental or substance abuse disorders were not only more likely to develop “mental” illnesses, but also “physical” ones such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and autoimmune conditions such as fibromyalgia.

The insistence by even progressive health advocates on sticking to the language of ‘mental’ versus ‘physical’ health harms sufferers of both, and also prevents us from examining the intersection of social issues such as poverty and inequality on public health. We have no hope of reducing the stigma around ‘mental’ illness or effectively preventing ‘physical’ illness until we conceive of the brain as an organ just as physical as any other part of our body, accepting that every part of our bodies from our brain to our gut are maps of our life stories, carved out in flesh and chemicals

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026 News / Cambridge ranks in the top ten for every subject area in 202623 January 2026

News / Cambridge ranks in the top ten for every subject area in 202623 January 2026 Comment / Cambridge has already become complacent on class23 January 2026

Comment / Cambridge has already become complacent on class23 January 2026 News / Palestine activists project slogans onto John’s24 January 2026

News / Palestine activists project slogans onto John’s24 January 2026