Nicola Sturgeon will find Indy Ref two harder than expected

The ‘unassailable’ position of the Scottish Nationalists does not mean that a second independence referendum is a foregone conclusion, argues Jake Dyble

At a time of political vexation, the SNP would appear to be sitting pretty. A Tory government in Westminster provides Nicola Sturgeon with the perfect bogeyman, and with Labour in total disarray the party looks unassailable in Scotland. They are blessed with well-marshalled grassroots support and canny operators at the helm. Governing in Holyrood is proving to be the electoral equivalent of having one’s cake and eating it. The party enjoys the benefits of government but can still blame Westminster when something goes wrong. In London, Sturgeon’s able lieutenant Angus Robertson occupies a secure position. Free from scrutiny himself, he peppers the flanks of Labour and Conservatives alike, scoring many rhetorical hits.

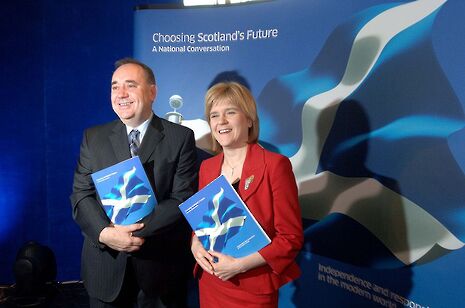

Best of all, ‘clean Brexit’ provides the SNP with the excuse it needs for a second referendum in 2018. If losing EU membership doesn’t constitute a ‘substantive change in circumstances’, it’s difficult to see what does. Theresa May must err on the side of hard Brexit or risk alienating the right of her party. Here, too, the SNP can have the best of both worlds. Sturgeon can appear balanced and reasonable for a time, seeking a seat at the Brexit negotiating table. When May inevitably rejects her demands, she will have her casus belli. For the party faithful, nothing less is enough. When Nicola Sturgeon announced the publication of a new independence referendum consultation in October, the conference room in Glasgow went crazy. This hotly-anticipated franchise reboot even comes with a catchy title: ‘IndyRef 2’ (This time, it’s personal!). And given the way Scotland voted in the EU referendum, IndyRef 2’s success seems a foregone conclusion to many.

But sequels don’t always capture the magic of the first movie – just ask Danny Boyle. It’s even rarer that they surpass the original. And the latest YouGov poll suggests that independence is no closer than it was first time around. Only 46 per cent said that they would vote for independence in a second referendum – an increase of just one percentage point since the 2014 vote. This apparently static figure conceals the fact that many voters have swapped sides since the EU referendum. A small number of people who voted to remain in both referendums now want to leave the UK, presumably to stay in the EU, but an almost equal number who voted to leave in both referendums now want to stay in the UK for the opposite reason.

“IndyRef 2 is more likely to be 2018’s summer flop than a blockbuster smash.”

It’s a complicated scenario, far more complicated than the SNP would have us believe, but it makes sense when you think about it. Some of those voted to remain in the 2014 referendum did so not out of deep conviction, but because they thought that the status quo represented the safer option. Now, an independent Scotland inside in the EU seems like the more certain path. Conversely, a number of those who rejected rule from Westminster are, understandably, even less keen on rule from Brussels. After all, the ideology of nationalism, even the civic nationalism of the SNP, doesn’t sit comfortably with the European project: if you believe that it is those who live in your country that are best placed to understand its needs, it makes little sense to seek oversight from a supra-national body. Nicola Sturgeon’s anti-Brexit rhetoric risks alienating those voters for whom the issue of sovereignty is paramount. On this issue at least, she can’t have it both ways.

This is not the only reason why Scottish independence is a more remote outcome than many expect: referendum fatigue will play a part. The people of Scotland have endured three referendums in the last six years. A recent Sunday Times poll found that 51 per cent do not want another vote on independence in the foreseeable future – only 27 per cent are in favour. When Alex Salmond billed 2014 as a ‘once-in-a-generation opportunity’ he didn’t add any caveats about changes of circumstance. How many wavering swing voters will choose to punish the SNP for dragging them back to polls? The SNP is surely right, at least in political terms, to leap at this second chance of independence, but they should not be surprised to find the opinions of moderate have hardened against them.

Then there is the recurrent question of finance which has dogged advocates of Scottish independence since the beginning: ‘The English steel we could disdain/ Secure in valour’s station/ But English gold has been our bane/ Such a parcel of rogues in a nation!’, as Robbie Burns put it. On this point the SNP may have some counter-arguments: post-Brexit, the prospects for ‘English gold’ appear rather uncertain and if the EU referendum showed anything, it was that economics isn’t everything when it comes to constitutional issues. With oil prices collapsing, however, the Scottish government budget deficit now stands at £14.8 billion a year. An independent Scotland would have a higher deficit as a percentage of GDP than any other nation in Europe, Greece included. To make a success of IndyRef 2, Sturgeon needs to convince a significant number of moderate remain voters to overlook that fact. In the event that she succeeds, she would then need to petition the EU for membership, which would surely demand that Scotland engage in significant ‘fiscal contraction’, reducing its deficit from eight to 10 per cent of GDP to a more manageable five per cent. Good luck selling that to the electorate.

The SNP may be running rings around the Westminster parties, but the latest figures are not encouraging as far as independence is concerned. IndyRef 2 is more likely to be 2018’s summer flop than a blockbuster smash

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025