‘Now You See Us’ at the Tate: generations of female artistic genius

Loveday Cookson reviews Tate Britain’s new exhibition on the achievements of female artists spanning four centuries

The first time I stepped foot in Tate Britain, I was freshly spat out from my first Michaelmas term and had arranged to meet my new London-centric friends, my escape from the countryside cutting through the sprawling winter break. As we spun through the revolving doors, I was flooded with anticipation, knowing the infamous delights that lay ahead. But as I stand staring at the press release for ‘Now You See Us’, the Tate Britain’s latest exhibition of extraordinary female artists, the words only eddy and swirl as I seek some familiarity, a name, any name that I recognise among the hundred-plus – I find two. I know nothing: two artists, two women. It’s not for a lack of artistic interest, I can rattle off the name of every member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with ease – but that’s the problem, the art world is a brotherhood. In 2022, 25 out of the 2391 artworks displayed at the National Gallery were made by women, just scraping 1%, the same level of name recognition I have for those exhibited here. Tate Britain’s new exhibition ’Now You See Us’ describes itself as a “major survey of women… who worked as professional artists over the last 400 years” as it pays “tribute” to the “legacy of these extraordinary artists”. Women’s work is reframed as professional prowess compared to the perception of women as “genteel amateurs”, as curator Tabitha Barber describes.

“The art is not purely limited to the domestic sphere or feminine subjects, but is also not degraded for adhering to these subjects”

The ethereal Invention by Angelica Kauffman – one of only two female founding members of the Royal Academy – is a fitting confrontation upon entry. We may dip our toes in, acclimatising to her accomplishment, before a rich narrative of brilliance unfolds as we move through the rooms, simultaneously navigating the progressive investment and acknowledgement of female creativity. Kauffman’s prominence resulted in Mary Black’s exquisite portraiture being attributed to Kauffman, the frame even bearing the inscription of Kauffman’s name. The existence of two female artists was clearly too complex a concept for exhibitors to understand, instead finding an ease in the hegemonic identity of Kauffman, the (only) female painter. Black was similarly denied payment comparable to her male contemporaries and was expected to take the commission as reward enough, illustrating how female labour was repeatedly reglossed as a generous donation of liberty by men.

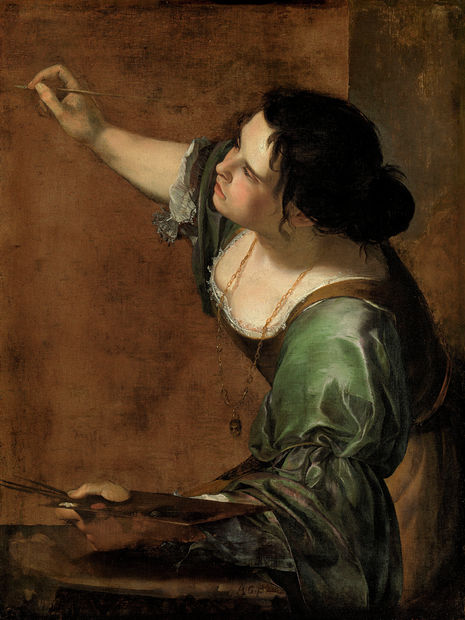

To omit Artemisia Gentileschi, who follows Kauffman in the display, is to deny the unfathomable strength of women. Having endured torture by testifying against her rapist, she proceeded to have an unparalleled level of success in her artistic career. This is not to let her biography dominate our objective appreciation of Gentileschi’s talent, but to comprehend the sheer resilience of female artists.

Moving through the exhibition, I am drawn to the quiet magnetism of Mary Beale’s oil paintings of her son. Beale’s brushstrokes radiate an innate tenderness, forging his luminous skin and golden locks with an inimitably maternal gaze. Joanna Mary Wells’ final painting, Thou Bird of God, with its gentle yet arresting outward glance, compels our attention; the sensitive ethereal backdrop is cut by the Pre-Raphaelite iconography of her striking red hair. The softness of style and sentimental subjects embrace typical aspersions of female art, revelling in their capacity for gentleness.

The art is not purely limited to the domestic sphere or feminine subjects, but is also not degraded for adhering to these subjects. ‘Just what ladies do for amusement’: Joshua Reynolds’ survey of ‘lesser’ art forms – embroidery, artificial flowers and anything considered inherently female – is emblazoned on the exhibition wall, offering an acute contextualisation of what Barber describes as the “hurdles” women had to overcome.

“They are women, but more significantly, they are artists”

Louise Jopling’s A Modern Cinderella casts off these limitations with the same ease with which we see the subject remove her evening gown. In an intimate invitation, the clock strikes midnight and a pink shoe is lost to the foreground. We are exposed to the vulnerability resting behind the facade of fairy tales and socially prescribed costumes. A mirror populates the background, staring out at us as the subject turns her gaze inward; we are left to confront suggestions, the objects that live only in the mirror and the narrative that lives in our imagination. While the subject’s face remains obscured, we are offered a glimpse into the real life of women, focusing on Jopling’s ability to render a history and geography of women and their spheres rather than an aesthetic survey of physical female beauty.

Standing on the cliff’s precipice, Laura Knight’s focal figure in The Dark Pool engages a similar facial indistinctness. The craggy rock face and sprawling horizon of blue, punctuated by the subject’s coral dress, is electric, foregoing the need for elucidation. Knight doesn’t painstakingly etch out every detail; instead, delicate white brush strokes flesh out the warmth of the rippling water. Deliciously vibrant, you can feel the waves enveloping your shoulders as you plunge yourself deeper into the painting.

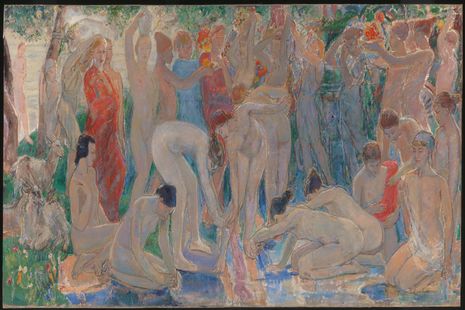

The exhibition aims to re-establish women’s place in our collective memories as “pioneers”, “professionals” and “highly productive artists”. But it does more than this. It does not implore an admiration for those it exhibits on the basis of sex alone, but allows their brilliance to shine irrespective of gender. It walks the difficult line between facilitating oppressed narratives without tipping into condescension, reducing the artists to simply female artists, or caveating their current success with exceptionalist narratives. They are women, but more significantly, they are artists, and thanks in part to the work of the Tate and this exhibition they may finally be seen. Not sequestered away in Royal Collections, or discarded to the footnotes of history, they are seen in conversation with one another, rather than peppering male achievements. “Despite being told they wouldn’t and they shouldn’t, they actually did it”; ‘Now You See Us’ surveys an entire horizon of female artists, traversing the oceanic divisions of media and time period with ease, as we navigate chronologically through a shared history, charting a course of hope for the next generation. It commemorates those who perpetually took the leap of the cliff into “the dark pool”.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025