Ignore the tabloids’ clickbait, Trinity’s Dean never said Jesus was transgender

A controversial service at Trinity College chapel was reported to have left worshippers ‘in tears’ after so-called ‘heretical’ claims that Jesus had a trans body – but the tabloids seem to have purposefully gotten the wrong end of the stick

When you think of Bridgemas, you often think of peaceful film nights with friends as work winds down, festive formals, and joyful choir services with mulled wine. Seldom, however, does the word Bridgemas conjure up the term culture war. That is, of course, unless you were attending Trinity College’s chapel service the other week, in which chapel-goers left in tears as a result of a supposedly heretical speech given by junior research fellow Joshua Heath and Trinity’s Dean, Dr Michael Banner, who stated that the side wound of Christ was similar to that of a vagina.

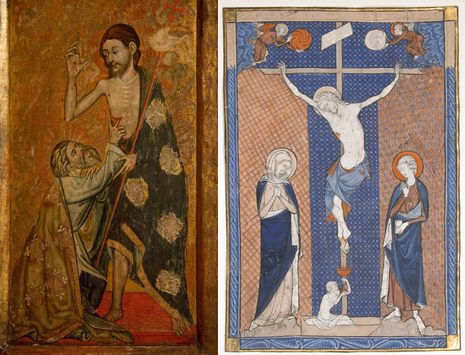

Heath later went on to state that “in Christ’s simultaneously masculine and feminine body in these works, if the body of Christ is as these works suggest, the body of all bodies, then his body is also the trans body.” The idea that Heath was somehow arguing that Jesus was transgender was quickly adopted by the press. The Daily Mail called it a “heresy row”, and the Telegraph went one further by stating that Heath’s sermon was a case of “rewriting history to appear relevant”. Altogether, it appears that Heath’s statement has been misconstrued as yet another act of ridiculous rewriting done by the woke brigade to completely erase history. Yet, through all of this, it appears there has been a massive misinterpretation. Nowhere in Heath’s statement does he claim that– just because Jesus’ side wound looks a bit like a certain female body part– the Son of God must be transgender.

Seldom does the word Bridgemas conjure up the term ‘culture-war’

In fact, contrary to several outraged reactions, this idea is not a modern one created to pander to the woke agenda. The book in which the illustration Heath references is included, Bonne of Luxembourg’s Prayer Book, is one of many pieces of devotional literature that fall into the Book of Hours category. These books, often containing similar images, were an extremely popular form of devotional writing often commissioned by wealthy women and there are genuinely thousands of manuscripts available. If any scepticism remains about whether or not these images are indeed meant to evoke the vulva, then they should be viewed alongside paintings of Christ from the medieval period in which the messiah is depicted with curvy hips and pronounced breasts. Still sceptical? How about considering the writings of several female devotional writers of the medieval period? Brigette of Sweden wrote about Christ’s pain on the crucifixion using the same language as that of a woman going through the throes of childbirth; Margery Kempe evoked Christ’s pain on the cross as she herself gave birth; and most obviously, the writings of Julian of Norwich where she states that Christ is our “mother”?

It is important to note that through looking at all these examples of devotional art and literature, the prevailing voices are primarily female. This draws upon the medieval idea of affective piety - or rather, the idea that acts of devotion should be in line with the bodily reality of the devotee. Ergo, if the worshipper was female, then Christ would often be feminised to inspire a bit of empathy between the worshipper and the subject. It appears that Heath may have been speaking in this tradition when he made his comments in Trinity’s service, which do actually argue that the body of Christ is subject to the bodily experiences of the worshipper.

This idea is not a modern one created to pander to the ‘woke agenda’

As to why these comments have been so misconstrued, I believe there are two explanations. One is that the medieval period– a period that is actually incredibly creative, vibrant and radical– is often depicted as a sad, grey period. We imagine that sad grey people just sat and did nothing, before dying at the ripe old age of 25. It seems infeasible, in these terms, to then imagine medieval writers ever depicting vulvas in art, especially in religious contexts. Secondly, an argument that is incredibly academic and nuanced has been commented upon without knowledge of the vast wealth of intellectual context behind the comments made. This nuance has unfortunately been left by the wayside to make way for sensationalist headlines sparking a debate that doesn’t even hold up to the comments made in the first place.

All this debate has really shown is the rift between complex academic debates and the press’ tendency to sensationalise and misconstrue. Their click-baiting headlines transformed what was otherwise a very warm statement on the accessible and welcoming nature of worship into a debate that directs outrage at a group in society who are facing enough unfounded hate as it is. So I shall finish this article by addressing those that are offended by Heath’s claims: put down your pitchforks and take a look at our radical, creative, and innovative past. Maybe you’ll find something new to talk about there.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026