‘Samurai: History and Legacy’ at the University Library

Staff writer Zoe Turoff reviews the UL’s latest exhibition which features Japanese archival material and charts the history of samurai

Tucked away in a basement room of the University Library, highlights from the UL’s extensive collection of Japanese manuscripts and woodblock-printed books show a side of the samurai rarely portrayed in popular media today. Originally derived from the word "suburau", meaning "to serve", the term "samurai" evolved to refer to those who held positions of authority in the household of nobility. Today, its meaning has been transformed even further, as modern depictions like the Japanese epic Seven Samurai (1954) or Tom Cruise’s The Last Samurai (2003) paint a picture of a violent, warmongering people.

“However,” says curator Dr Kristin Williams, “the imagery we usually see is as much legend and mythology as it is history.” Instead, she wants visitors to “question their assumptions about Japan while they explore and examine the rare books and objects in the exhibition. We may think of weaponry and armour when we think of samurai, but there was far, far more to their story.”

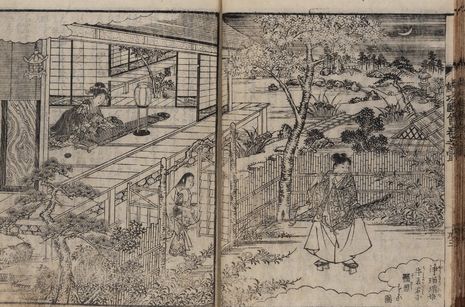

The beginning of the exhibition traces the origins of the samurai in twelfth century Japan. At this time, a shift in power from the imperial court in Heian (now Kyōto) to the shogunate (military government) in Kamakura, facilitated by a series of violent rebellions, led to the emergence of legendary tales of heroism and tragedy. One prominent figure, whose story features in various manuscripts throughout the exhibition, was Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189), younger brother of the first Kamakura shogun. Far from the modern image of the fierce and vicious warrior, Yoshitsune appears here as a tragic hero, engaging in the gentler arts of the samurai. In a reproduction of an illustration of Yoshitsune kunkō zue, we see his musical side: he sits in the garden of a young maiden, who falls in love with him while he plays an instrument that resembles a harp or zither.

Treasures from one of the world’s most important collections of Japanese literature are now on display at @theUL!

- Cambridge University (@Cambridge_Uni) January 29, 2022

Explore the free exhibition 'Samurai: History and Legend' – running from 22 January to 28 May 2022: https://t.co/SmgPw7Objg#ULSamurai #Japan

An appreciation of music was part of a wider cultural context of the samurai, which was guided by Buddhist practice. In the Yuishinken kadensho, a master passes down the secrets of flower arranging to a disciple. Accompanying illustrations show how flowers should be arranged on Buddhist altars.

"Centuries of complex history were collapsed into the sort of memorable images”

In the 1870s, the foundation of a modern army in Japan rendered the samurai obsolete. But Dr Chris Burgess, head of exhibitions and public programmes at Cambridge University Library, explains how their legacies lived on: “Centuries of complex history were collapsed into the sort of memorable images of the samurai that we’re all so familiar with today.” Despite these stereotypes, Dr Burgess hopes this exhibition will encourage visitors “to examine, through the extraordinary books, manuscripts, and objects on display from our collections just what kind of samurai is revealed to us.”

Perhaps the most unexpected kinds are those that don’t conform to dominant gender stereotypes often associated with these strong, “macho” warriors. Women, too, were part of the samurai class, and often trained in martial arts for the purpose of protecting their families. Stories centred around female protagonists feature heavily in this exhibition: the Honchō Jokan (mirror of women of our land), for example, is a counterpart to biographies of male military generals, such as the Honchō hyakushōden (biographies of a hundred generals from our country) displayed nearby.

"Perhaps the most unexpected kinds are those that don’t conform to dominant gender stereotypes"

This particular manuscript is opened to an illustration of a young woman in the midst of a brutal act of revenge: the artist has portrayed the moment she stabs Sadamitsu Kyūzaemon, who murdered her brother when he refused to offer his sister as Kyūzaemon’s bride. This unbridled feminine strength is echoed elsewhere in the story of Tomoe Gozen, in the Heike monogatari: the manuscript reads, “with her lovely white skin and long hair, Tomoe had enchanting looks. An archer of rare strength, a powerful warrior, and on foot or on horseback a swordsman to face any demon or god, she was a fighter to stand alone against a thousand.”

The dim lighting of the UL’s Milstein Exhibition Centre protects the objects against light damage, but also adds a sense of drama to the illustrated folios of the objects on display – many of which have never before been seen by the public eye. One of the first displays centres on the Azuma kagami (“Mirror of the East”), one of the first Japanese books in Britain upon its arrival in 1626. This volume, which was originally misidentified as a Chinese manuscript and bound upside down, provided the foundation for one of the world’s most important collections of Japanese literature outside Japan when it entered the Cambridge University Library in 1715.

Now, it goes on display for the first time alongside samurai helmets, a whimsical volume of cats dressed as Edo-period warriors, the strikingly beautiful Buddhist text, Lotus Sutra (or Myōhō rengekyō) and even a book of manga (drawings) by the famous Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. Curator Dr Kristin Williams admits, “the hardest thing about curating this exhibition was choosing only 60 objects from a total collection of more than 130,000 Japanese items!”

This free exhibition is running from January 22 to May 28, 2022 and can be found in the University Library.

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026