Victims of Circumstance: Reading Hardy’s Two on a Tower

In her third column, Shona Whelan reviews the obscure yet thought provoking Hardy novel ‘Two on a Tower’

Ask any random person their favourite Hardy novel, and chances are they’ll tell you Tess of the D’Urbervilles. If you’re lucky, they might say Far From the Madding Crowd (and you’d be even luckier for the person in question to have actually read either of them – perhaps not unsurprising, with each clocking in at roughly 8 hours to read – unless they’re also an English student). Some more adventurous types might plump for The Mayor of Casterbridge, and the subversive ones might go for Jude the Obscure.

But the real overlooked gem of Hardy’s works is one of his minor novels, Two on a Tower. Sure, you might just think I’ve picked it for a laugh – as my dad lovingly reminded me before I started here, “No one really likes classic literature, you all just pretend you do!” – but to me, this tale of star-crossed lovers is underrated, not least for its controversial views of class and gender roles. It’s not surprising it isn’t better remembered – one contemporary critic called it Hardy’s “worst yet” – but this in itself raises questions of what themes are allowed in literature and who dictates this.

The novel begins with a bleakly Gothic overview of the Constantine manor and grounds – fitting, when it becomes clear that Lady Viviette Constantine is trapped in an abusive, loveless marriage with her adventurer husband Sir Blount. Hardy’s descriptions of the “sob of the environing trees” and “moaning cloud of blue-black vegetation” are unsettling for the lack of control they symbolise: this is something Viviette struggles with throughout the novel.

"Hardy’s descriptions of the 'sob of the environing trees' and 'moaning cloud of blue-black vegetation' are unsettling for the lack of control they symbolise"

More urgently, this asks us to consider how far Viviette is a victim of circumstance. The Victorian era wasn’t exactly renowned for championing women’s rights, and Hardy’s descriptions of character and place show an awareness of this: what might be beautiful in one light is also an inescapable trap in another – in this case, the trappings of marriage and status. This is why I admire the novel – for whatever its faults may be, it is sensitive to Viviette’s plight (and I may say more so than in Tess, but that’s an article in itself).

Breaking up the “gloom and solitude” is our introduction to the dashing young astronomer Swithin St Cleeve. This is handled well by Hardy – on the face of it I realise it may well seem a ridiculous pairing, but Swithin’s tenderness and earnest nature are endearing. The mansplaining of astronomy to Viviette is admittedly much less so, but I suppose I can’t have it all. Again Hardy demonstrates a sensitivity here – both characters do feel well enough fleshed out that the melodramatic plot doesn’t obscure them.

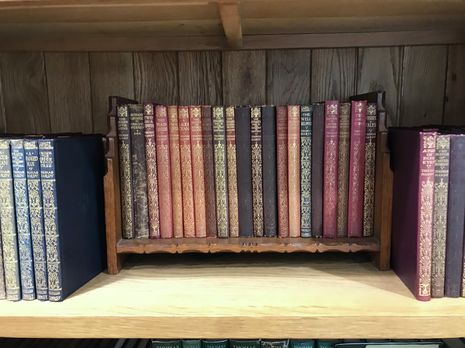

Afternoon all Hardy fans, another beautiful painting by Donald Maxwell, this time for

- Debs Green - Jones (@DebsGreenJones2) October 6, 2020

'Two on a Tower' #ThomasHardy #oldbooks pic.twitter.com/M3Ibth4p1m

Though in hindsight it might just be that the other male characters are so vile that anyone would look better in comparison, Swithin does have a certain charm about him, and for all his comet-obsessed philosophical ramblings, Viviette’s relationship with him does seem authentically romantic. Not that this matters in the eyes of the law – and several mishaps later, their relationship is tragically fated – but this poses another challenge to conventional norms (which the radical feminist in me greatly enjoyed).

I’m making no claim of this being a strikingly feminist or class-inclusive text – the constant manipulations of both gender and class roles throughout are ultimately fruitless – but it certainly does raise some talking points about power. Other characters – Viviette’s deeply misogynistic brother Louis, Swithin’s deeply misogynistic uncle Jocelyn and the deeply misogynistic Bishop (do I sense a pattern emerging?) – are the gatekeepers of change and happiness, and Hardy’s choice to make these characters obviously villainous was a successful one.

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026 Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026

Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026 News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026 Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026

Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026