Decadence: a man’s world?

Arts columnist Shona Whelan discusses the history of female writers in the Decadence period

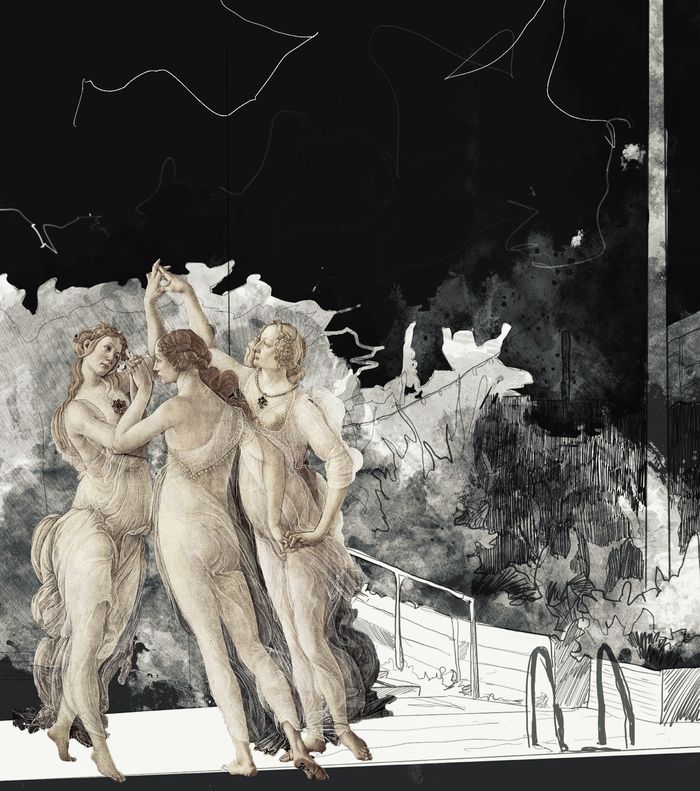

Decadence, the late 19th century arts movement exploring aestheticism and excess, was unsurprisingly a male-dominated experience. Hedonism, personal and political scepticism, and materialistic tendency were hallmarks of the movement – things typically only accessible to those who were suitably white, wealthy and male (because, of course, women were simply there to fulfil the ornamental purpose Decadence so aspired to).

“Decadent works were a force to be reckoned with”

In fact, you needn’t be an English student to recognise one particularly popular figure: Oscar Wilde. Perhaps best remembered for the Gothic-tinged The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which beauty and morality are uncomfortably aligned via the beautiful Dorian Gray’s lapses into crime – reflected on his increasingly grotesque portrait, Wilde popularised many of the conventions of the Decadent movement.

Perhaps fewer people realise that the godmother of the movement, however, was a woman herself: Rachilde. This being the preferred pen name of French Symbolist – and later, Decadent – author Marguerite Vallette-Eymery, it likely afforded her some of the anonymity necessary to present such depraved topics with such grandeur. Her works were famed for being enticing yet amoral; both passionate and scathing in their depictions of contemporary issues and gender roles. Female-authored Decadent works were a force to be reckoned with, and perhaps this is why their popularity is seeing something of a resurgence.

In some ways, the female Decadence writers can be viewed as reactionary. Authors such as Rachilde, among others, reject natural imagery in favour of the glory of man-made art – a refreshing twist on the tendency to align women with all things pretty and floral (because we are clearly just pretty but ultimately ineffectual, right?) Rachilde drew particular attention for her focus on gender roles – prominently in her novel Monsieur Venus, which drew both criticism and admiration for the fantastical erotic plot and overt scenes of cross-dressing. Though she refuted the label of feminism, this established an important message: perhaps hedonistic excesses and world-weary delight in perversion weren’t just for men.

Female authors in the Decadence movement were also politically subversive, perhaps with more power than we give them credit for. One example would be the high-profile lesbian writer Renee Vivien – her Sappho-esque autobiographical poems, often extreme in their romantic despair, were surprisingly popular during her lifetime – a testament to the hold women had over the movement. Though neither she nor her counterparts received quite the same attention initially, a revival of interest in her works is an encouraging sign of things to come for marginalised poets.

“Perhaps hedonistic excesses and world-weary delight in perversion weren’t just for the men.”

Equally, the context in which some of these authors were writing is particularly interesting – take Russian writer and editor Zinaida Gippius, whose romantic poetry was a mainstay of Russian literary tradition. Though her Collection of Poems 1899-1903 more closely aligns with symbolism, being an originator of aesthetic minimalism, it was well received by the Decadent-allied poets. In rejecting tradition, these women were important trailblazers in reforming an otherwise male canon, and the romantic extremes of their works are as resonant now as ever – perhaps more so in the heightened emotions of the pandemic and the state of women’s rights globally.

Looking back on it now, it seems odd that the movement is almost exclusively remembered for its male writers. In some ways, 21st century ideas of decadence are more commonly associated with women – the booming self-care industry, for example, has marketable femininity firmly in its grasp with lures of lushly scented candles and luxurious bubble baths (because clearly addressing actual patriarchal oppression is just a step too far – after all, we can vote now, so what’s the problem?). But the real power of poetry lies in the voices and emotions it creates space for, and that is something that is needed now as much as – if not more so – ever.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026