When Harry Met Maggie

Martha French, as part of Varsity Art’s Valentine’s musings, looks into the queer art power couple of Maggie Nelson and Harry Dodge

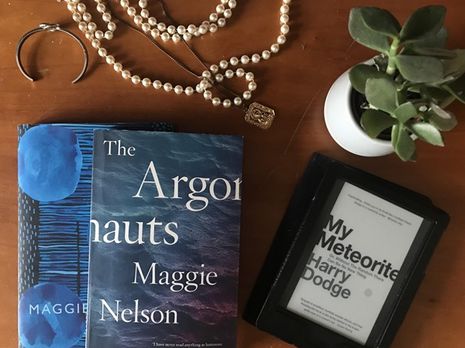

Maggie Nelson and Harry Dodge’s marriage in Los Angeles, 2008, was a rushed affair. ‘It suddenly seemed as though Prop 8 [a California ballot proposition which would eliminate same sex couples’ right to marry] was going to pass’, Nelson writes in her 2015 work The Argonauts, continuing: ‘Poor marriage! Off we went to kill it (unforgivable). Or reinforce it (unforgivable)’. The Argonauts is a scrapbook of theory, memoir, and quotation revolving around Nelson’s pregnancy, in which Nelson figures Harry as ‘an attempt to conjure the feeling of "and" or "but"’ and their marriage as 'an endless becoming'.

Maggie Nelson is a writer and academic who has “spent a lifetime devoted to Wittgenstein’s idea that the inexpressible is contained – inexpressibly! – in the expressed”; she has written on everything from murder to ‘cruel’ art to motherhood. Harry Dodge is a trans artist best known for his visual art, including the 2001 queer buddy film By Hook or By Crook, in which he wrote, directed, produced, and starred. In recent years, Dodge has turned towards sculpture and performance-based pieces, with his 2019 exhibition User exploring the relationship between man and machine. It is this dogged pursuit of interrelation that drives the work of both artists; as Dodge observes, 'We’ve been on the move – mixing with each other and things – forever'.

“It is odd to see Nelson and Dodge’s relationship outside of its textual form”

During the first weeks of the US lockdown, Dodge’s first book My Meteorite: Or, Without the Random There Can Be No New Thing (a self-proclaimed 'meditation on matter, and a book about bonding or, say, love') was published. With the pandemic preventing a traditional book tour, Dodge opted for an interview conducted from home by Nelson, which was broadcast live on Penguin’s Instagram account. It is odd to see Nelson and Dodge’s relationship outside of its textual form – they rarely appear together in public and neither use social media – and so mentions of their son Iggy (in the next room playing Minecraft, apparently) and an introduction to their yappy poodle were made all the more charming by their unusualness.

The couple sat talking about their experiences of quarantine and creating art, providing a moving 36-minute insight into what felt like daily chatter flecked with offhand wisdom. In the interview, however, the couple refuse to marry themselves to the verbal alone: 'sometimes literary language doesn’t make space or room for all the ways that we make things', Nelson admits, revealing that it’s often things as miscellaneous as snakeskin or film montages that illuminate the flaws in her own writing and teach her how to reform her words and thinking.

Nowhere is this tension explored more fiercely than in Nelson’s 2009 lyric essay Bluets, in which she argues 'Life is a train of moods like a string of beads and as we pass through them they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows only what lies in its focus. To find oneself trapped in any one bead, no matter what it’s hue, can be deadly'. On the surface level, Bluets is an expansive, intensely poetic text about Nelson’s life-long infatuation with the colour blue, chronicling everything from Joni Mitchell lyrics to grief to Platonic philosophy. Yet (as always) what is really happening is something more complicated; in Nelson’s most visceral moments of divulgence, we see a testament to love in all its inexpressibility.

Nelson’s writings are carefully confessional texts obsessed with boundaries and their breaking, from the corporeal to the artistic. The Argonauts is peppered with her and Dodge’s conversations about the limits of language: what can truly be said, what it can actually show, and to whom: writers and readers, speakers and listeners alike. While Nelson cites the capacity of language as 'how I feel able to keep writing', Dodge believes once something is named 'we never see it in the same way again'; it is this question of possibility, of what can and should be shared, that hums through the rest of the book.

“their intimacy spreads beyond their partnership into their connections with art”

Dodge insists: 'I’m quite a private person [...] But books, writing, these things are constructions, missives from an artist to the world, meant for sharing, meant to prompt sociality'. And so, their intimacy spreads beyond their partnership into their connections with art, theory, and ultimately others. It enriches their love and demonstrates what it is to form a bond, as well as how conjunctions and divisions alike are crucial to the maintenance and renewal of such an attachment. In our present moment, these musings on the weight of connection (and what it means to resist emotional isolation) feel more prescient than ever.

What is so powerful about Nelson and Dodge’s love – and its product, their texts – is their willingness to understand themselves through each other, or even their consciousness of this necessary willingness. In exploring love through art and art through love, the couple invite their readers to do the same, to – as Dodge proposes in My Meteorite – 'risk contact with unfamiliar humans – in order to find myself in the heaving maw, the protean, flowing haemorrhage of universal energy'. They are involved in what can only be understood as an artistic exercise: that of redefining and queering their own love, and in turn creating a world of brackets, asides, and footnotes, in which everything is malleable, fragmented, ineffable, and yet deeply interpersonal, unshakeable, and frankly literary all at once.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026