The Literature of Love

In time for Valentine’s Day, Varsity Editor Georgina Buckle hand-picks five texts which muse on love, in all its multitudinous expressions

Time and again, writers and readers return to the theme of love. Love seeps into the crevices of our everyday lives: it is in family, in friendship, in our bond with pets, with literary figures, and in romance. The myriad of ways that we experience love is often best articulated in literature. Here, I have selected five beautifully different texts – spoilers ahead! Collectively, they explore a diverse range of relationships and how love is at the essence of human life. Love, in its varying forms, is our reason for being. As Victor Hugo writes in Les Misérables: “To love or have loved, that is enough. Ask nothing further. There is no other pearl to be found in the dark folds of life.”

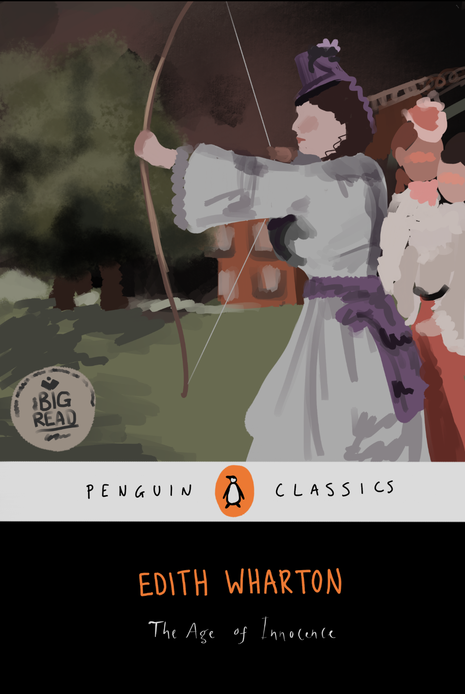

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

The Age of Innocence is partly a story of forbidden lovers: Newland Archer has his life dictated for him by the upper echelons of New York society, but the arrival of Countess Olenska muddies his plans. By the unwritten, tribal laws of their society, the two are not to be. And yet, they fall irrevocably in love: “Each time you happen to me all over again.” They know they must sacrifice each other and in one vignette, an aggrieved Newland bends to kiss Ellen’s satin shoe. The scene is drenched in sorrow, for it is the chaste kiss of unconsummated, forbidden passion.

The novel shows that true love involves protecting the other person, even if you must surrender them to another: as Ellen says, “I can’t love you unless I give you up.” In fact, Wharton wrote an alternate ending where they run away together, are eventually unhappy and separate. Wharton demonstrates that sometimes love isn’t sustainable in the real world – it is far more perfect preserved in memory. In her life, Wharton also deeply craved a long-term companionship that she never found: one where sexual desire, kinship and intellect all coincide. Like Newland in the novel’s closing, she may have realised what she was missing: “the flower of life”.

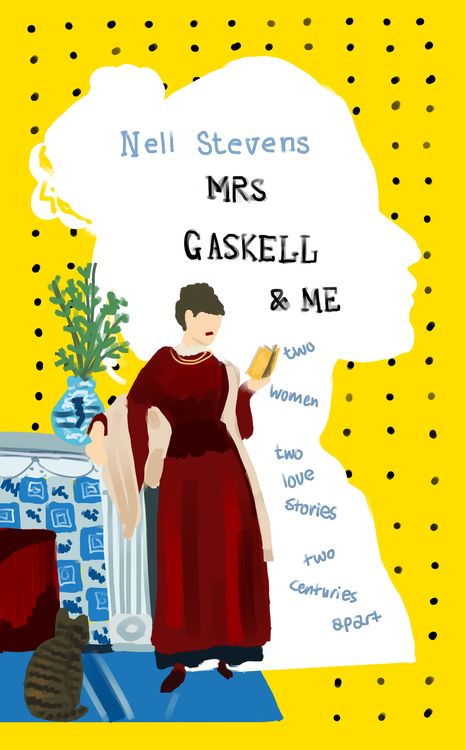

Mrs Gaskell and Me by Nell Stevens

Sometimes the fiercest adorations are for people we have never even met. In this case, for the writer Elizabeth Gaskell. The Guardian aptly describes Stevens’ novel as a ‘partly autobiographical romance, [and] also a love letter to Elizabeth Gaskell.’ It opens on the author as a post-graduate working on a thesis about Gaskell. Under the pressure of piling academic stress, a deteriorating relationship and health issues, how does Nell seek solace? By immersing herself into the life of Gaskell as she left Manchester for Rome in 1857, a trip which led her to meet the supposed love of her life, Charles Norton.

Chapters of Stevens’ novel are devoted to vividly imagining Gaskell and Norton’s encounters, guided by historical detail but fictionalising their romance. Sometimes it feels feverishly written. Nell undergoes a break-up and projects a sentimental version of fulfilled love in the re-imagining of Gaskell’s life. Her writing becomes suspended in the hazy area between fact and fiction: where does Nell’s life start and Gaskell’s end? When Nell crumbles, her idolisation of Gaskell is what remains strong. Stevens’ novel explores how literary love is as real and unwavering a love as any other.

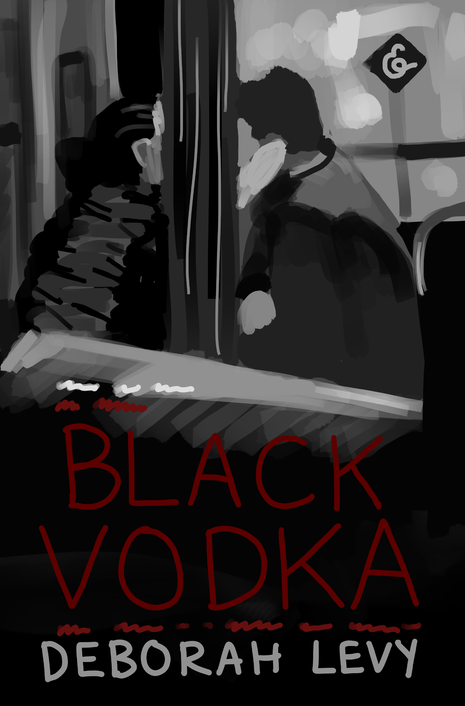

Black Vodka by Deborah Levy

Deborah Levy has said that most of her work is about narratives with holes – she is never trying to heal these holes, but instead to understand them. Her short-story anthology Black Vodka does exactly that. The ten short stories are about romantic and familial relationships in all their flawed, broken and diverse ways. Levy’s writing cuts to the quick of modern love and how our interactions with others are simultaneously a strange, confused dance with ourselves. One story titled ‘Pillow Talk’ deftly writes about a cheating partner. Rather than escalate the plot into melodrama, Levy magnifies how detached their relationship is; Ella and Pavel are dislocated from one another, physically and emotionally, but also dislocated from themselves. Levy’s work keenly evades boring or easy story lines. Read Black Vodka if you want to see love through a kaleidoscope: constantly changing, never expressed in one simple way.

‘Funeral Blues’ (1936) by W. H. Auden

The poem ‘Funeral Blues’ was initially written by Auden as a mocking satire of a dead politician. But the meaning of Auden’s words have since been completely spun on their axis by the 1994 film Four Weddings and a Funeral. This iconic British film has instead immortalised the verse as a heart-breaking dirge to a lost loved one. Now, it’s hard to read it any other way. The poem does not only express grief, but testifies to the immeasurable greatness of the love that the two people had – it was everything they once breathed: “He was my North, my South, my East and West, / My working week and my Sunday rest”. The verse bluntly conveys the pain of realising how colossal love is in the passing of everyday life. Without it, it does not make sense for the world to go on as normal: “The stars are not wanted now; put out every one”.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson

Published just last week, Open Water is Nelson’s debut novel about the relationship between two young Black British artists. Their bond is set amidst a complex background of race, masculinity and identity, where they struggle to make sense of the world but find solace in each other.

Nelson shows how effortless love is. The novel’s epigraph, quoting Zadie Smith’s NW, encapsulates that: ‘There was an inevitability about their road towards one another which encouraged meandering along the route.’ Nelson’s writing is imbued with a gentle lyricism that traces the curves and contours of true love. The two artists just fit together “like it is an everyday”. Open Water illuminates a simple truth about love: it is an easiness, a returning home.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026