I am not every woman

Emily Sissons questions whether Mary Wollstonecraft’s feminist legacy is best represented by the humdrum nudity of Maggi Hambling’s ‘conversation starter’ statue

Mary Wollstonecraft, an 18th century feminist activist and author of the seminal work ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’, has recently been commemorated by a memorial in Newington Green Park, Islington in North London.

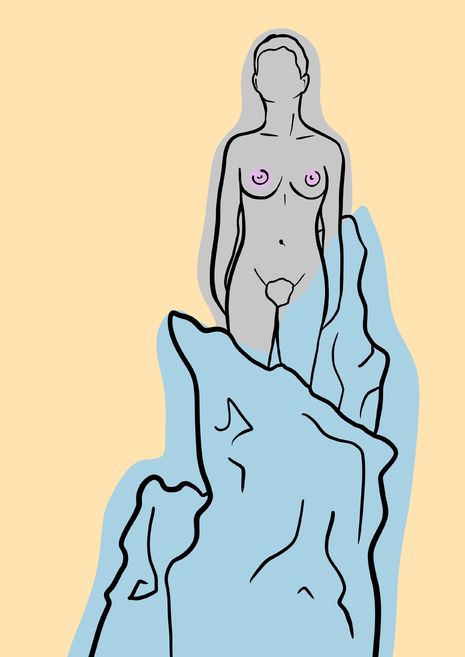

The statue features a small naked female figurine, named the ‘Everywoman’ atop a large swirling mass, representative of female forms. It has been created by the often-controversial artist Maggi Hambling, who argues that the statue is not actually ‘of’ Wollstonecraft, but is simply ‘for’ her. The statue has attracted heavy criticism because the slim, conventionally attractive, silvery-white ‘Everywoman’ clearly does not represent every woman, as Hambling claims it does. Regrettably, Hambling’s attempts at inclusivity are actually very exclusionary, particularly towards people of colour and plus-size communities, or indeed anyone who does not fit these extremely narrow, Westernised standards of beauty.

"Hambling has defended her choice to present Wollstonecraft as naked by arguing that clothes would restrict her female form"

The statue also insults Wollstonecraft’s legacy, by implying she is not considered worthy of a statue explicitly commemorating her enormous contributions to the feminist movement and the advancement of women’s education, despite being regarded by some as the ‘mother of feminism’. It is obvious that men, who are celebrated by over 90% of London’s statues, would not be represented in this way. Statues commissioned for men usually present realistic embodiments of one male, in a flattering and dignified manner. Men are able to be exclusively themselves, whereas women cannot, as they can never be separated from the identity bestowed upon them as nothing other than gendered objects.

Hambling’s statue is a brash and slightly obvious attempt to generate public attention to the lack of recognition Wollstonecraft has received in British feminist history. Admittedly, this has succeeded and created a discussion surrounding Wollstonecraft in a way which a more conventional, non-sexualised statue may not have done. However, this debate is only short-lived on major news sites and trending social media, and so ultimately what we are left with in the long-term is little more than a regrettable eye-sore.

"This statue reduces Wollstonecraft to a sexual object in precisely the way she abhorred, viewed through the male gaze"

Additionally, a statue emphasising the naked female form only further highlights issues experienced by Wollstonecraft during her lifetime, when her feminist contributions were disregarded in favour of a focus on her sexualised body. Wollstonecraft engaged in numerous sexual relationships outside of marriage producing two children. When this was publicly exposed, it resulted in the destruction of her reputation and led to her subsequent ostracization from the popular feminist community throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. She therefore already has a troubled legacy of unpopularity, and this statue simply furthers this narrative without providing any recognition of her significant achievements, such as establishing a girls’ school close to the statue’s location.

The naked female body can be seen as a powerful symbol of a refusal to be censored or conform to a patriarchal society’s expectations. Hambling is correct in arguing that this refusal was certainly embodied by Wollstonecraft through her own actions, such as moving to France alone to participate in the French Revolution. Wollstonecraft criticised the fact that Queen Marie Antoinette was forced to use her feminine sexuality to influence the decisions made by the French monarchy. The patriarchal standards of the time stated that the primary role of Marie Antoinette as a female royal, or indeed any female, was as child bearer – only her naked body was useful. This statue reduces Wollstonecraft to a sexual object in precisely the way she abhorred, viewed through the male gaze.

This statue is therefore less a commemoration of Wollstonecraft, as it evidently does not mirror her actual beliefs, and is instead more an opportunity for the designer to showcase their own political agenda. Hambling has defended her choice to present Wollstonecraft as naked by arguing that clothes would restrict her female form. However, her nudity is equally restrictive – it limits observers to looking only at Wollstonecraft’s body, and not her feminist contributions to advancing the rights of women.

Recently, there have been very well-publicised instances of the removal of statues, which no longer fit society’s standards of what is socially acceptable, from public places. Notably those of men linked to colonialism and the slave trade, such as the Edward Colston statue in Bristol. Just as there has been considerable focus on how Britain publicly represents its role in colonialism, in the future an even stronger emphasis on considering how female figures are represented will hopefully develop, especially those from marginalised communities.

This raises the question – in another century, will future generations tear down the Wollstonecraft statue?

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025