The ‘great white space’ at Kettle’s Yard

Alice Brewer explores the intriguing use of gallery space to place new accents on works in the house at Kettle’s Yard

In July this year, Ahdaf Soueif announced that she was resigning from the Board of Trustees for the British Museum. In a blog post for the London Review of Books, she wrote that it was not due to one particular issue. However, her main contention appears to be the institution’s persistent neutrality with regard to the repatriation of items that are essentially stolen goods, and the cleansing of the reputation of British Petroleum at a time of climate crisis. The museum, Soueif writes, is not an inherent force for good in the world. Its claim to be an ethical and modern institution relies on it using its academic and cultural clout to promote the interest of the ‘young and less privileged’. But in its neutrality on anticolonial action and the climate crisis (at least in terms of its sponsors), the British Museum is failing those who Soueif argues it must make it its business to educate and protect.

Equally, the blank walls of the building itself are not neutral. They occlude the material conditions that allow the artefacts to exist there: the years and years of colonial robbery and the dubious money that sustains the exhibits’ upkeep. Emancipated from their original settings and set among the airy rooms, the artefacts lose large parts of their history, appearing instead as miraculous autonomous survivals of individual brilliance.

Fifty miles northeast, in Cambridge, the house at Kettle’s Yard offers a different story. It accommodates the works that H.S. – ‘Jim’ – Ede collected, and he lived there between 1956 and 1973. It figures as a museum of the habits and tastes of this twentieth-century art collector. Stewards stress the purity of the relation between artist and collector: I’m told that Ben Nicholson would give Ede any painting that he had failed to sell for the price of the canvas; Joan Miro exchanged his painting for the price of a Parisian coffee. There are no labels to justify or date the works, conferring an aesthetic parity between the paintings, furniture and plants.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s 1914 sculpture ‘Dog’ is used as a doorstop in one of the rooms upstairs, though this is actually a recast made in 1965. The original was broken, possibly by one of Ede’s children: he claims they sometimes took the sculpture to bed as a replacement teddy. The sculpture’s insouciant placing and the fact that it is a reproduction profanes the idea that there is some sort of quasi-theological importance residing in the original artwork. This gesture furthers Kettle’s Yard’s opposition to the aestheticist idea of the prime value of the work of art being in its uniqueness, its originality – the kind of idea propounded in the reams of text in the British Museum or the National Gallery which seek to show that the work is the original, and thus of great artistic and cultural value. Instead, Kettle’s Yard seeks to show aesthetic value in the habitual and the functional.

I am currently sitting and typing. I am wearing plastic earrings with lemons on them. They are based on one of the first things I saw in the house: a wide grey pewter bowl with a lemon placed northwest of centre. Jim Ede made it as a teaching aid for when he gave tours of his house to university students. It is a coda of Miró’s ‘Tic Tic’ (1927). The lemon reprises the pale-yellow circle in the bottom-right corner of the painting. Ede would remove the lemon from the bowl, then replace it. Without the lemon, the bowl becomes inert, insistently grey. Likewise, the painting loses its balance without the yellow: too much of that dark hallmark Miró blue.

Like Gaudier-Brzeska’s ‘Dog’, my earrings have a more subtle visual value, used and staged among many other more functional items in everyday life. I like to think of it as an echo of that subtlety of space and position that compelled Ede to make the bowl in the first place, and the fact that the museum remains largely the same as when he once lived there.

On some of the downstairs tables, hundreds of pebbles have been arranged in bowls and spirals, lit up by window-conveyed light. They suggest Marcel Duchamp’s ‘readymades’: his inert unmodified mass-produced objects placed in galleries, the most famous of which was denied submission to the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917, even though the event claimed that any submitted piece of art would be displayed. The found material of both Ede and Duchamp is transubstantiated by the pieces’ environments, breaking into that nebulous category of ‘art’ and mocking the surrounding blank space on which so much depends.

The pebbles become artistic wholes, just as the white walls of the Louvre make its works appear as autonomous and whole

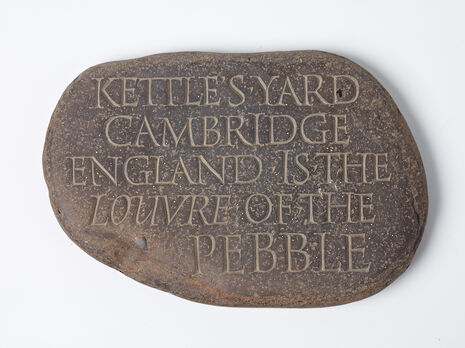

A 1995 work by Ian Hamilton Finlay comments on this transformative power of space. It is a flat brownish-grey pebble declaring in engraved serifs that ‘KETTLES YARD / CAMBRIDGE / ENGLAND IS THE / LOUVRE OF THE / PEBBLE’. The line breaks, half-compelled by the natural shape of the pebble, tempt the reading eye to put pressure on the definite articles of the poem, stressing the importance of the specific location and position of the specific object. The pebbles become artistic wholes, just as the white walls of the Louvre, or other more traditional galleries, make their works appear as autonomous and whole.

Both subjects broached in this article have been commented on by other articles in Varsity. Alycia Gaunt has noted the lukewarm attempt of the British Museum to “decolonise”, and Damian Walsh discussed Kettle’s Yard’s use of space. What I hope to have shown is that these practices are linked. Kettle’s Yard is a remarkable gallery, offering up a different way of seeing and appreciating the work of art. Whilst its own practice and mythos of authenticity sometimes feels laboured, it foregrounds the visual tricks that art galleries and museums use to confer ideas about the values placed on art – whether it be the more functional, holistic philosophy of Jim Ede, or the aestheticist and universalist one of the British Museum or National Gallery. The gallery reminds us that space is not neutral, but plays a constitutive role in the appreciation of a work of art, or a historic artefact. When thinking about the role of colonialism in the shaping of the eighteenth and nineteenth public museum, or the role of climate crisis in sustaining them today, the ideology of the great white space should be kept in mind.

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026