Art notes from the big city: Gauguin Portraits

The National Gallery’s exhibition demonstrates Gauguin’s narcissism, but that’s what makes his art, argues Grace England

Content note: This article contains discussion of exploitative relationships.

Narcissism, savagery, fantasy, manipulation: these are the words that come to mind after seeing Gauguin’s portraits. The narcissism hits you instantly on entering the first room: on placards nestled among self-portraits of the artist as Christ, the curators go so far as to introduce him as ‘undoubtedly self-obsessed’.

The exhibition snakes through seven rooms, each charting a different period of the French artist’s life, including his notorious association with the island of Tahiti. This show is particularly significant as the first ever exhibition of Gauguin’s portraits alone. Given the theme, I wondered, would the curators would give a voice to the subjects of the portraits on display?

He was the ultimate muse for his own creative genius

While the exhibition is keenly aware of the range of subjects in Gauguin’s portraits, one gets the sense that when Gauguin himself is not in them, there is something missing. Even the portraits of his own French family seem strangely impersonal. The faces are turned away, the eyes invisible. There is a much greater sense of intimacy between subject and viewer present in Gauguin’s self-portraits, which are vibrant and intensely engaging. Gauguin fixes his signature side-eye stare upon you with such directness that you almost feel uncomfortable. He highlights his aquiline nose; he paints himself surrounded by his own self-portraits; he even paints himself as Christ. He was the ultimate muse for his own creative genius.

Gauguin remains focused on the self in his association with Tahiti. It has long been known that his association with Tahiti is an unsettling one, carrying a dark undercurrent of sexual exploitation. According to the curators, Gauguin believed himself to be the ‘embodied link’ between Tahiti and Europe. The exhibition makes a lot of Gauguin’s fascination with the ‘savage,’ a romantic ideal of pure primitiveness which was uncorrupted by Western society. Yet when he appears to paint the supposed ‘savagery’ of Tahiti, in reality he manipulates the culture in order to fulfil his own Western fantasy of what he believed ‘savage’ to be.

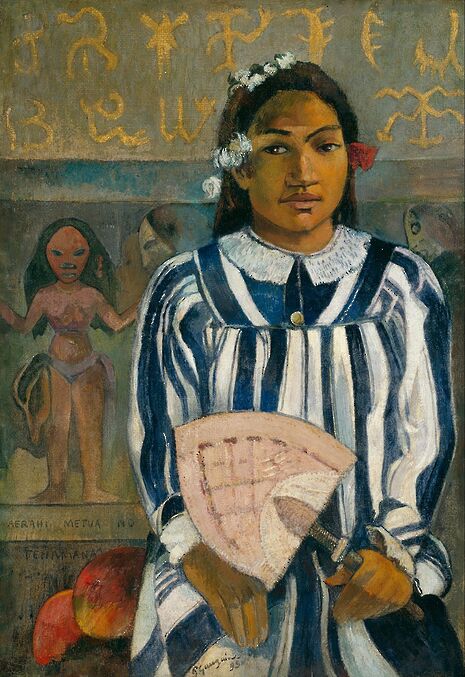

The prime example of this is Arii Matamoe (The Royal End). Here, Gauguin depicts a supposed local custom of displaying the head of the deceased Tahiti king, a play on traditional western portrayals of John the Baptist. However, this scene was entirely invented; no such tradition was used in Polynesian society. It is a ‘savage’ fantasy of Gauguin’s, a manipulation of the culture around him which seemingly left him dissatisfied. When he depicts Tahitian women in elaborate pictorial narratives (such as Teha’amana in The Spirit Watching) they are often depicted sexually, a way of Gauguin fulfilling his own ‘savage’ and misogynistic sexual fantasies.

It is a ‘savage’ fantasy of Gauguin’s, a manipulation of the culture around him which seemingly left him dissatisfied

One of the most prominent features of the exhibition is that dark eyed, often sober figure of Teha’amana, Gauguin’s Tahitian ‘wife’, now believed to have been as young as thirteen when they first met. In multiple portraits, she is ‘dressed up’ in colonial style, more of a mannequin than an artist’s muse. Her lack of voice is highlighted by the exhibition, which points out the sad truth that her experience of their relationship was never recorded. In one troubling depiction she is seated in a rocking chair, eyes downcast, enveloped in a strangely ageing, if brightly coloured, missionary dress, her wedding ring glinting overtly. While Tahiti was a French colony during his period, and had largely adopted colonial dress and customs, Teha’amana still appears here like a little girl, playing at being a colonial housewife, a role in which she has been cast without her consent.

Gauguin’s representation of women seems even more pressing in the present day, where privileged Western white men like Epstein and Weinstein, who took advantage of vulnerable young women, are now slowly being brought to justice. For all that, though, we cannot deny Gauguin’s genius in these works. Colour often radiates off of the canvas, and their composition is imaginative and immersive. While they may create uncomfortable, intense atmospheres, they certainly have emotional impact. The curators’ opinionated guide to the exhibition is unusual but vital in contextualising Gauguin’s works. The context may be disturbing, but it ultimately helps us understand and appreciate his art.

It is Gauguin’s ability to visualise his own fantasies and obsessions that makes his work so unique. He lives and breathes through every one of his portraits, whether they depict him or not. You leave the exhibition truly feeling you have stepped inside Gauguin’s vision, however self-centred it was.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026