Fitz Favourites: Rue St Vincent

In the first instalment of a series, Damian Walsh explores one of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s lesser-known works

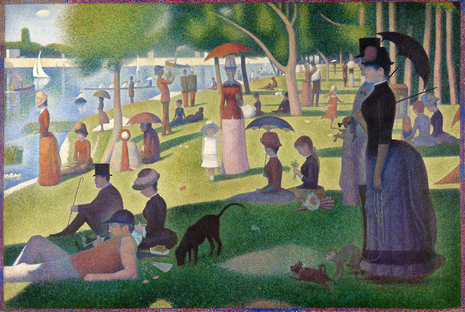

If, on a cold afternoon, pushing against the wind, you turn off Trumpington Street and into the Impressionist Room at the Fitzwilliam Museum, craning your neck to look for Monet or Renoir, or Seurat’s much more famous study for Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte, you might miss a tiny, portrait-sized painting of a street. Hanging above a richly decorated table, and bracketed by blank space on the wall around it, it looks almost apologetic in its smallness. Easy to overlook.

Maybe that’s appropriate: it’s a painting of a narrow, unremarkable street that you might just as easily miss in your rush from one place to another. How often, after all, do you really look at King’s Parade as you hurry down it, 5 minutes late for a lecture?

How often, after all, do you really look at King’s Parade as you hurry down it, 5 minutes late for a lecture?

And yet, Seurat’s Rue St Vincent, Paris, in Spring is one of my favourite paintings in the Fitz, and (I like to think) an invitation to pause and notice the small details around us. A shadow of feathery leaves perches atop a lamp post; strips of sunlight falling across the path seem to form a stairway towards some vague white shape in the middle distance, shining with an almost ethereal brightness into an otherwise ordinary street.

To get more technical, it’s one of the few paintings in this room not on canvas but on a wooden panel. Panel paintings are, I think, an underappreciated medium. There’s a wonderful richness to wood-based paintings that you don’t find on canvas: shadows appear deeper, light glows in a very different way. For me, I also can’t help but feel some grand transhistorical connection back to the painters of Byzantine or Orthodox icons, who traditionally used panels to produce their glittering works of devotion.

Seurat, admittedly, probably chose wood for his Rue St Vincent because it was cheap rather than for any grand spiritual significance. At the start of his career, he often carried small panels around with him, which he used to produce around seventy oil studies. He called these his croquetons (little sketches). He even painted on cigar boxes at times. Still, I think there’s some resonance in this solid medium.

We probably know Seurat best as the ‘pioneer of Pointillism’, but he never liked the term, preferring to call his theory by the verbose title of chromoluminarism (quite a mouthful). And it’s the luminosity of this piece that makes it so arresting: light of all sorts of hues seems to shine out from unexpected places, thanks to Seurat’s distribution of coloured strokes. The spring leaves glow gold and blue; the left-hand wall a mosaic-like mixture of indigo and brown.

Maybe we can apply the same willingness to see our local streets in a new light.

It’s exciting to think that, as he painted the Rue St Vincent, Seurat was quietly devising – honing and trialling – what would become his new theory of art. That which would later enable his huge (and hugely famous) Sunday Afternoon – and inspire artists like van Gogh – is here perceptible only as spots of orange among the leaves, smudges of brown in shadows on the path.

Seurat’s spring street might be far removed from Cambridge’s arctic winds; Bohemian Montmartre might be 285 miles away (thank you, Google Maps), but maybe we can apply the same willingness to see our local streets in a new light. (And personally, the painting always reminds me of Burrell’s Walk near the UL, but maybe that’s wishful thinking.)

Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky thought that the purpose of art is to ‘defamiliarise’ ordinary things – to make us look at the mundane world in a new way, as if for the first time. Anaïs Nin later expanded the idea: ‘It is the function of art to renew our perception. What we are familiar with we cease to see.’ In my own over-ambitious way, I’d like to attempt something similar, in miniature, in this column. We’re in the privileged position of being surrounded by art in Cambridge, spoiled for choice. In my fourth year here, I know how much of it I’ve stopped noticing. I’d like to look again at works we’re all too guilty of overlooking – small works, hidden works, or ones that are just easy to stop noticing. Spend some time on Seurat’s Rue St Vincent – maybe you’ll see the not-too-dissimilar Cambridge streets in a new light.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026