Stories from a Carnal Imagination

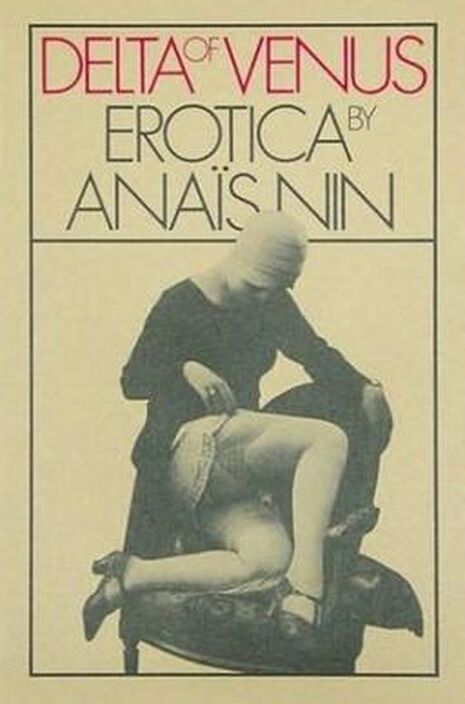

Rachel Weatherley finds both literary value and feminist ambiguity in Anaïs Nin’s erotic collection, Delta of Venus

Content note: This article contains discussion of sexual assault and violence

Before E.L. James, there was Anaïs Nin — French-Cuban author of erotica, prolific diary keeper and polarising member of the post-war avant-garde. Delta of Venus, a collection of fifteen short stories, conjures up a ‘glittering cascade of sexual encounters’ where female sexuality is centred and transgressive desires are not shied away from. This intoxicating world of libertines and lotharios, show girls and aristocrats, captured so beautifully by Nin’s electrifying prose, deserves the attention of a day off in Grantchester, surely the Soho of the Cambridge bubble, in order to immerse oneself fully in a world where morals run amok.

“Whether Delta of Venus can be inducted into the canon of sex-positive authorship is a polarising question”

The anthology had a peculiar genesis, being commissioned by “The Collector” - a clandestine moniker belonging to an Oklahoman oil baron and son of a clergyman, Roy M. Johnson. He wanted erotica, paying $1 a page, an offer Nin gladly took up. But this prosaic and transactional origin does not supplant the depths of these tales. What sets this collection apart from contemporary works of the period is the richness with which Nin explored the terrains of the sensual and the sexual as a pleasure-seeking woman.

We accompany her to a number of insalubrious locations - damp Parisian backstreets, seedy Swedish bars, Brazilian favelas - and we play the voyeuristic spectator. Some of the more jubilant stories juxtapose much darker episodes. In ‘Linda’, we see a loving and fulfilled marriage: husband constantly woos wife, in turn she seems gratified and liberated.

Other stories prove to be coarser, ‘The Hungarian Adventurer’ an unforgiving narrative of one man’s life of promiscuity, pursuing cabaret girls and sadomasochistic sexual encounters, before disappearing into the night. Tonally, what remains constant is an keen understanding of the psychological aspects of love - we know that Nin is pushing boundaries in writing about women and sex so candidly, what elevates this is her non-judgemental descriptions of the bisexuality and gay love, as well as more fetishistic desire.

In keeping with the trajectory of many lauded writers, Nin’s literary career was not without tumult. She would first occupy a position marginal to mainstream literary circles (Elizabeth Hardwick, in the pages of the Partisan Review, called her ’vague, dreamy, mercilessly pretentious” and “a great bore’), before gaining prominence and celebrity close to the end of her life as a symbol of unfettered female sexuality. In truth, such divisiveness seems coherent with the very essence of her writing. Explicit depictions of rape, incest and abortion make the currents of betrayal and adultery that feature elsewhere in the collection seem quotidian.

“Libertines and lotharios, show girls and aristocrats, captured so beautifully by Nin’s electrifying prose”

Whether Delta of Venus can be inducted into the canon of sex-positive authorship is a polarising question, one that is compounded by the violence that punctuates most of the stories. That a considerable portion of the female characters do not consent to the sexual acts sits more than uncomfortably in a modern context. One also wonders why Nin, who in many respects outdistanced the social confines of the 1940s, was hesitant to give her female characters any real agency. Interview footage proves illuminating: “I’m not a belligerent suffragette.” said Nin. “A woman is responsible for her own freedom. She can get it without declaring war on men. What I don’t like about the feminists’ movement is that it says it’s your fault that I’m not free. That’s not true.” Such comments seem misguided: are we right to feel disappointed?

Her diaries are more indicative of her personal feelings about the erotica she wrote, and her complicated relationship with ‘The Collector’. On the topic of sex, she exclaims, ‘you have taught [me] more than anyone I know how wrong it is not to mix it with emotion, hunger, desire, lust, whims, caprices, personal ties, deeper relationships that change color, flavour, rhythms, intensities.’ Here, Nin voices disgruntlement at the prevalence of the male gaze in literature, something Delta of Venus endeavoured to rupture.

It is in the drawn out passages of introspection and the luxuriant minutiae of detail where we see significance beyond the pornographic: ‘and in his eyes he had the look of the cat who inspires a desire to caress but loves no one, who never feels he must respond to the impulses he arouses.’ Her prose is fervent and intense, always with a lyrical, sibylline quality that no doubt evokes the visceral reactions she intended.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025