third space ii: exhibition preview

third space is back for its second instalment, following the success of last year’s exhibition. Sarika Datta sits down with curators and contributing artists to discuss why creating and providing these spaces within Cambridge is so important.

“It’s about championing and channeling diasporic narratives which are often neglected”, states Anki Deo (Pembroke College, Second Year), “we’re here to facilitate these stories, in whatever forms they take”. third space is back for the second year of its annual exhibition, which defines itself as an artistic showcase of experiences of those who identify as from neither “here” nor “there”.

Following last year’s exhibition, founder Jay Parekh, now graduated, is trying to generate more awareness than ever of the importance of providing an artistic space for people of colour, particularly within Cambridge. “The third space exhibition allows people to tell their stories and to discuss the vast array of issues that affect people of colour”, he remarks. As Anki, co-curator of the exhibition points out, it is an exciting time to be at Cambridge, wherein increasingly more diverse tastes finally have the opportunity to be catered for and being both racially and politically engaged is no longer as solitary an endeavour as it has been in the past.

Edwin Boadu (Trinity Hall, Second Year), fellow co-curator, mirrors this sentiment, viewing third space as a pastiche of those who felt they never quite blended into a community or particular sphere. He reveals that seeing such a space being created in Cambridge is “heartwarming” and provides a sense of relief and comfort: “I moved from Italy to the UK seven years ago and am ethnically Ghanian, thus the notion of diaspora is one that resonates deeply with me. In spite of ethnicity or language abilities, I always felt I was never quite enough to belong to one community”.

Kalvin Schmidt-Rimpler Dinh (Trinity Hall, Masters), also a co-curator, expresses the sense of disheartenment that can arise navigating Cambridge as diasporic. Being raised in North Carolina and Berlin respectively and of both Vietnamese and German descent, Kalvin occupies a space of composite identity which he describes as carrying “several anchors” to which he holds equally legitimate claims. He also notes his adoption of British culture, having just started his fourth year studying at Cambridge and how this myriad of affiliations has created a wariness to any strong associations with one particular notion of identity. However, he argues that it is through being placed in this position of hybridity that he is able to perceive and better understand cultural tensions and his study of post-colonial literature and theory has further opened up these realms of understanding that have previously been sidelined in his personal history.

“it is perhaps these disjointed gaps which enable children of the diaspora to look inward and create their own spaces of identification, spaces that are fiercely personal and unashamedly bold”

third space is, for many students, the first exhibition they will have submitted work to. Anki recalls the white Barbie wearing a sari that she submitted last year, a gift bought in Mumbai from her grandmother. She laughs as she recalls the cutting ironies the Barbie represented. “She bought it for me so I could be in touch with my heritage but it only reinforced the idea of colourism and whiteness being good.” This year, her submission takes the shape of a traditional form of Hindu art, an Indian floral decoration known as Rangoli. Deeply personal and sensitive, the piece was inspired by her desire to explore the toxic delineation of South Asian countries while toying with the idea of using an overtly religious medium to promote a message of embracement. Being ethnically Indian, yet growing up in London her whole life, Anki describes coming to Cambridge as experiencing “a race awakening”. She recounts her relationship with identity having oscillated from being buried and ignored to a state of confusion and upset, until finally settling into a place where she can now navigate these contentions from a perspective of acceptance.

Running themes throughout conversations touch upon language and clothing as a means of self-expression and describing how the inability to speak one’s native language can produce an intense feeling of displacement. However, it is perhaps these disjointed gaps which enable children of the diaspora to look inward and create their own spaces of identification, spaces that are fiercely personal and unashamedly bold.

For Mia Watanabe (Trinity College, Third Year), wearing her haori, a piece of traditional Japanese clothing, is a small but profound statement on her autonomy as a mixed-race queer woman and gives her comfort in navigating the complexity of intersectionality. “Being both ha-fu (a Japanese term for half-Japanese people) and being bi-sexual often places me in a social category of double-negation. I am neither Japanese, nor not-Japanese; neither British, nor not-British; neither exclusively attracted to people of the same gender (as myself), nor not exclusively attracted to people of the same gender”. She recounts having tried to to embrace this double-negation for many years, in the hope of gaining a position of acceptance by those around her, both in Japan and in the UK. However, it is precisely in letting go of trying to grasp a socially accepted identity in both countries that she has found contentment in this affirmative third space, a third space occupied by her, and solely her.

Similarly, Mishal Bandukda (Sidney Sussex College, Third Year) of British-Pakistani descent likens third space to a haven of solace for those who “fall between the gaps”, confiding how the exhibition emerged at a time when she truly needed it. Depicted above wearing a necklace constructed of intricate Sindhi metal and bead work, she explains it was the first piece of traditional jewellery she bought with the intention of pairing with Western clothing, regardless of the binary juxtaposition the combination initially appeared to create. “I thought of it as cool rather than embarrassing to wear; it’s a symbol of how far I’ve come in combatting internalised shame about my heritage”.

Often, members of the diaspora occupy a space whereby the conventional expectations of skin tone and appearance are challenged, as experienced by Saffie Patel (Corpus Christi College, Second Year) who reflects on the struggles of being half-Indian and half-Turkish: “I often worry that my attempts to be ‘Indian enough’ come across as disingenuous when by all accounts I am white passing and privileged.” It is often the painful process of learning to recognise that other people’s assumptions do not validate or invalidate an individual’s notion of identity, and it is this path Saffie finds herself gradually navigating.

“I often worry that my attempts to be ‘Indian enough’ come across as disingenuous when by all accounts I am white passing and privileged.”

For contributing artists Arjun Singh-Lotay (Girton College, First Year) and Victoria Ayodeji (Queens’ College, First Year), it will be the first time that either of them will submit to an exhibition. Growing up in East London and with ancestral roots in both the Punjab and Kenya, Arjun identifies as belonging to several diasporic subsets and describes how this has been sewn into the fabric of his daily life from tying his turban in Kenyan style to the everyday enjoyment of adding masala spices to his PG Tips.

Similarly, Victoria, of British-Nigerian identity, also grew up among the wealth of diversity of East London and both artists recall the exploration of self-discovery this allowed them. Victoria’s navigation between cultural spaces as a child is patterned with intimate memories of accompanying her mother to Dalston Market to buy ingredients to cook Nigerian delicacies like jollof rice and listening to the thriving music genre, Afrobeats. Despite having never been to Nigeria, Victoria notes that this dislocation hasn’t prohibited her from creating her own space, given the flourishing community of second-generation British-Nigerians she has grown up with. Interestingly, her submission, titled my first time in Africa was not my parent’s birthplace, is composed of a series of photographs taken during her trip to The Gambia in 2016. She recalls the questioning of her dual identity that she experienced during her time there due to her inability to fluently speak a Nigerian language. “I’m slap bang in the middle – I’m not British but I’m not Nigerian. I’m British-Nigerian.” Arjun reinforces this feeling of occupying multiple spaces, describing it as “the shady space in the middle of a Venn diagram” and this sentiment is further echoed by Anki as she remarks, “it’s not about the number of circles, but most importantly the midpoint between them”.

After discovering his grandfather's old film camera in the attic this summer, Arjun’s submission focuses on capturing his experiences of navigating selfhood; “I wanted the lens which my Bapu Ji used to capture Britain in the 1970s to be the lens I used to experience Britain in the 2000s.” The photographs range from images of Arjun growing up with his “little topknot dressed in school uniform”, to capturing celebrations for the festival of Vaisakh in Southall, the bastion of British-Asian culture which allowed the diaspora a place to discover itself.

For many students of colour coming to Cambridge, the obstacles they can encounter are overwhelmingly disorientating and dislocating. Creating platforms such as third space not only permits these artists a platform of self-expression and solace, but it serves as a celebration for students to understand each other’s work and assist one another in their journey of identification.

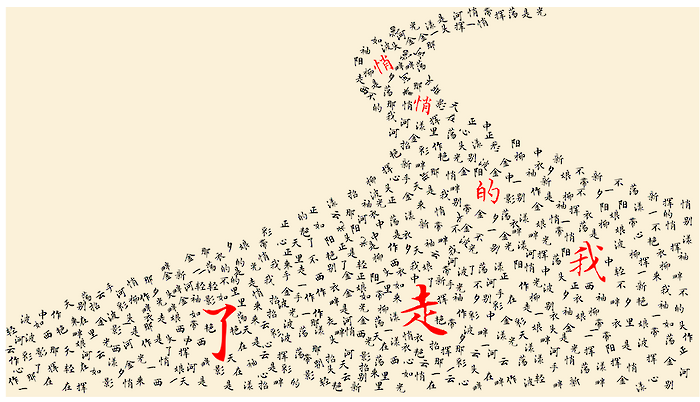

For Arjun, third space is a way for him to give back to a community to which he is grateful to for the help he received in discerning his multifaceted identity. For Kalvin, it is a path through which he can explore the relationship between object and memory, delving into the story of his own family’s migration stemming from the Vietnam War.

Collecting submissions from such a wide array of mediums is a testament to the complexity of stories being told about the experiences cultivated as a person of colour. “One of the really beautiful aspects I always find is that even if you take two people who have similar narratives on paper, their work and their outlook will be so much more than just facts such as where you call home and where your parents are from. Standing alone, none of these is ever going to be a full enough picture”, asserts Anki. Representation, dislocation and marginalisation are pervading themes amongst submissions, but these are heeded alongside themes of liminality, freedom and beauty, all of which Jay hopes to expand outside of Cambridge and into a wider context: “I want to keep expanding third space as a way to give people of colour the opportunity to tell their stories in other cities as well as commission work from rising artistic talent”. In an increasingly divided and hostile world which forces categorisation and sticks labels where they are unwanted, it seems that third space has come at the very time we need it most, generating the nuanced and multifaceted conversations that must be had in order to move forward.

The exhibition third space will be held at Sidney Squash Courts on Saturday 26th January, 7-11pm, with a film screening at 8pm and spoken word and musical performances at 9pm. On Sunday 27th, the exhibition will be open from 10-5pm for standard viewing.

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

![How to Create an Attractive Freelancer Portfolio [5 Tips & Examples]](https://www.varsity.co.uk/images/dyn/ecms/320/180/2026/02/vitaly-gariev-ho2tNOWZYXM-unsplash-scaled.jpg)