Xu Zhimo and the poem we walk past everyday

Jonathan Chan unpicks the life and work of the eminent 20th-century Chinese poet, a beloved figure who built the first cultural bridges between China and Cambridge

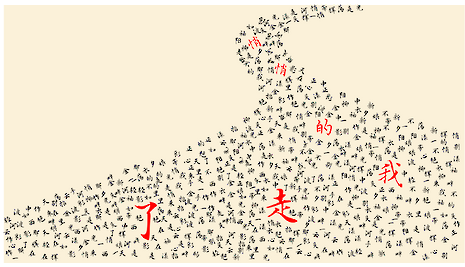

“轻轻的我走了,

正如我轻轻的来;

我轻轻的招手,

作别西天的云彩。

Very quietly I take my leave,

As quietly as I came here;

Quietly I wave goodbye

To the rosy clouds in the western sky.”

- Xu Zhimo, ‘Saying Goodbye to Cambridge Again’ (再别康桥)

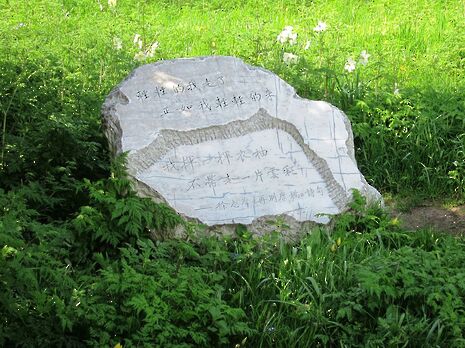

The above lines have entranced generations of students of Chinese literature. Inscribed in a stone of white marble within King’s College, the famous words of Xu Zhimo continue to enrapture the imaginations of droves of Chinese tourists. It is unsurprising to see such groups congregating around the stones in eager anticipation, paying homage to Xu’s powerful lyric by taking photos and admiring the college grounds. For many, a trip to Cambridge is a literary pilgrimage of sorts, albeit in a language familiar to few Cambridge students.

The influence of Xu Zhimo in contemporary Chinese literature cannot be overlooked, in large part owing to his status as a major contributor to modern Chinese poetry. Born in Zhejiang province in China in 1931, Xu’s death at the age of 34 in a plane crash has only served to elevate the sense of mystique that surrounded him. The juxtaposition of his picturesque verse and early demise has facilitated his mythologisation amongst his readers. Journalist David Cox writes that Xu would go down as a cult figure in modern Chinese history, immortalised through his premature and tragic end, illicit love affairs and success in introducing western forms into Chinese literature. A seminal figure, Xu’s poetry is often featured in the Chinese literature syllabus as an example of the modern poetry movement in the early 20th century, whether in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Singapore.

A mingling of his external encounters with the beauty of the River Cam and the backs and his inner sense of longing

After a period of studying economics and politics in the United States, Xu arrived in Cambridge to study at King’s College. Critic Lai-Sze Ng argues that it is in Cambridge that Xu experienced his literary awakening as a student. The flexibility of his arrangement as a “special student” was such that he could sit for any subject, allowing him to experience intellectual engagement without the pressure of taking examinations. Xu studied and fell in love with English romantic poetry, which he translated with great meticulousness. In his brief literary career, Xu produced translations of poetry by William Blake, Thomas Hardy, Katherine Mansfield, Matthew Arnold, and Christina Rossetti, amongst others. It is these poets that would stand to transform his poetic craft.

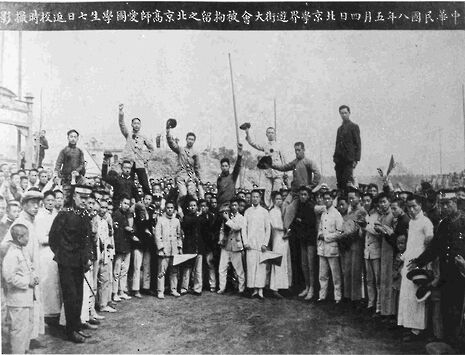

Xu’s transference of romantic ideals and forms to his poetry lead to marked innovation as he sought to break way from the constraints of literary formalism in Chinese literature. He is regarded as one of the first Chinese writers to successfully naturalise Western romantic forms to Chinese poetry, no doubt a consequence of his experiments in translation. Moreover, Xu was also known for his use of vernacular varieties of Chinese, a departure from the insistence of the literary establishment on using classical Chinese. This places Xu in the company of other writers and intellectuals from the May Fourth movement, an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement that emerged out of student protests in Beijing in 1919. Their efforts strove to engender a shift towards a populist base within the cultural and intellectual spheres, as is amply reflected in their writing.

What distinguishes Xu from his contemporaries is the fact that while most realist writers situated their writing within the context of mainland China, Xu is celebrated for his writing about foreign locales. Such was the depth of his affection for Cambridge that Xu addressed it as his 乡(xiang), or native dwelling. Perhaps it is unsurprising that his most famous works about Cambridge were composed on his return to China between 1922 and 1928. As Xu writes in his essay, The Cambridge I know, “[…] listening to the sounds of water under starlight, listening to the sounds of night bells in a nearby village, listening to the mooing of tired cows at the riverside, is one of the most magical experiences I had in Cambridge: the beauty of nature, serenity, harmonising in the privities of this starlight and light of the waves, by chance flood into your inner sensibility.”

The juxtaposition of his picturesque verse and early demise has facilitated his mythologisation amongst his readers.

The combination of intense nostalgia and an outflow of powerful feeling inflected his poetic reconstruction of Cambridge, a mingling of his external encounters with the beauty of the River Cam and the backs and his inner sense of longing. In Saying Goodbye to Cambridge Again, Xu writes:

“那河畔的金柳

是夕阳中的新娘;

波光里的艳影,

在我的心头荡漾

The golden willows by the riverside

Are young brides in the setting sun;

Their reflections on the shimmering waves

Always linger in the depth of my heart.”

This combination of natural imagery, sentimental yearning, and prosodic elegance has continued to enchant the Sinophone world and draw them to see Cambridge as Xu once did. It is no wonder that Xu’s life and poetry continue to inspire pop songs, gardens, and television dramas. It is also not uncommon for his lines to be quoted on the graduation posts of Sinophone students on social media. More recently, cuttings from the “golden willows” in question will be presented by King’s College to Xu’s home town of Haining, his school in Hangzhou, and Peking University as a gesture of friendship.

When I first read Xu’s poetry as a curious first-year, I did not find myself quite as moved as I thought I would be. There was something of his writing that I found too saccharine and sentimental. I could not help but notice the ways in which the English translations of his poetry resulted in the inelegant disappearance of elements of rhythm and rhyme. Yet, as the year went on, I began to find myself slowing down on walks and cycles along the backs, eyes drawn to the ways in which daylight broke on the rippling water, or how the willows fluttered gracefully in contrast to the stoic King’s Chapel. In learning to see Cambridge as Xu once did, I found a new depth of appreciation for each day that I’ve spent here, and for the privilege of living in a place that is beautiful when we remember it to be.

As I packed my bags and looked at my college for the last time of my first-year, my mind began to drift to Xu’s lines:

“悄悄的我走了,

正如我悄悄的来;

我挥一挥衣袖,

不带走一片云彩。

Very quietly I take my leave

As quietly as I came here;

Gently I flick my sleeves,

Not even a wisp of cloud will I bring away.”

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026