In defence of Maurice Sendak

Natasha Walden argues why children’s literature should not cushion the younger generations from life’s reality

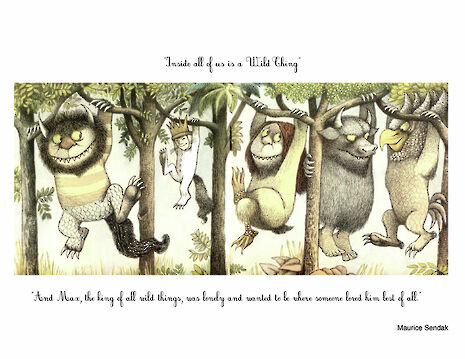

When I was a child, Maurice Sendak’s books were ones I only pulled off the shelf and pressed upon my dad when feeling particularly brave. I would stack books on top of them before bedtime so as not to glimpse the bared teeth of a ‘Wild Thing’ or the lion who swallowed ‘Pierre’ in one gulp. Yet they held an allure that few children’s books did: a belief in children’s ability to tackle both light and darkness.

Controversy has peppered Sendak’s work: accusations of impropriety, of themes too dark for our children’s innocent eyes. A copy of In the Night Kitchen was burnt by a school librarian in 1972 after outrage at the nudity of the little boy Mickey, who falls from his bed “into the light of the Night Kitchen” and is baked in a cake against a Brooklyn-esque skyline of milk bottles and trains made of loaves of bread.

I had largely forgotten, or had never consciously processed, the painful truths expressed in Sendak’s work. It was memories of the bizarre illustrations which had drawn me to recently purchase a copy of We are all in the Dumps with Jack and Guy for an ill friend finding it difficult to read for sustained periods of time. Upon opening the copy myself however, I saw what had truly enthralled me both as a child and now.

We are all in the Dumps with Jack and Guy features a barely-clothed baby living on the streets lined with houses of newspaper, who is stolen by a mischief of rats. My mind flicked through the trove of Sendak’s books in the mind of my (sometimes) suppressed inner-child, and remembered a little boy called Pierre who responds “I don’t care” to his parents’ every plea, until he is gobbled up by a lion. I remembered Hector the Protector who is sent alone into the woods, and of course Max who sails alone for over a year, to where the wild things are. My ‘natural’ reaction to this was ’Oh my goodness, outrage, impropriety, immorality!’. Yet I had not felt traumatised by such books when younger; rather, the memories I had of them were exhilarating. Oddly, Sendak’s work seemed to frighten me more as an adult than as a child.

“Our children cannot entirely avoid exposure to ‘grown-up’ issues”

Our knee-jerk reaction to the many horrors and heartaches of adult life is to construct a wall around our children. We must, however, remember that although rules of common sense apply, we should be careful with the extent to which we sugar-coat and sanitise. Our tendency to see such themes as inappropriate blinds us to their merit. Sendak’s work is not merely documentation of doom and gloom but has a bitter sweet balance; it grapples with darkness whilst retaining a powerful sense of hope.

We see Jack and Guy rescue and appear to co-parent the baby; Hector the Protector declares “I hate the queen!” as he tames and rides the forest lion; Mickey escapes the night kitchen in a plane fashioned from cake batter; the sister rescues her kidnapped sibling in Outside Over There. We see children be resourceful, brave and rebellious in the face of fear and loneliness. It was this that drew me to Sendak’s work, as I stood, age five, on the edge of our sofa as my brother imitated a Wild Thing, holding my hands up and shouting ‘BE STILL!’. Being King of the Wild Things was empowering and electrifying.

In We are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, we see children “lost”, “tricked”, “TRUMPED”, “dumped”, standing outside a very familiar looking gold-plated tower. Sendak’s message, then, is clear. Our children cannot entirely avoid exposure to ‘grown-up’ issues: homelessness, financial difficulties, fractured families. Sendak, a gay Polish Jew living through the AIDS epidemic in Brooklyn, son of troubled parents who were Holocaust survivors, with aunts and uncles upon whose ‘crazy eyes’ he based his ‘Wild Things’, recognises in the difficulties that he himself faced, the need for honesty. Childhood is never entirely easy; for many it is miles from it.

The almost complete control that we – as adults – have over the media young children are exposed to comes with the responsibility to protect, yes, but also a responsibility to educate, to inform, and not to patronise. Without recognising the troubles that children experience how can literature play its formative role in helping us understand ourselves and the world around us? If we do not give children tools with which to tackle the bits of adult life that can seep through the cracks of the well intentioned yet manufactured idyllic childhood, we are doing more harm than good. It is often more our fear of seeing children tackle difficulties than actual danger posed, that creates such boundaries of propriety

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025