The tension of the landscape

In his latest column, Joseph Krol discusses the birth of the landscape as an art form, and explores its implications for our view of Cambridge

Three miles west of Cambridge stands an unparalleled viewpoint. Situated on one of the few features of significant height in the vicinity of the city, the ascent may be a little tougher than one is used to. But, after a few minutes, one goes through a wooden gate, turns into a sloping field, and there it is – the surprisingly striking sight of the quintessential Cambridge landscape.

The landscape is a venerable art form, though perhaps not as venerable as one might think. Of course, they have been incorporated into paintings since time immemorial, but in the Western tradition it took a long time for landscape to be regarded as worthy of painting in its own right. Some of the first great steps towards this genre arose in Italy, towards the end of its great rebirth of art.

The Tempest is a wonderful work of the Venetian Renaissance. The background is integral to the painting: were the clouds not barely cracking, were the lighting not so soft, the emotions it elicits would be utterly different. The storm is not yet here, but we can sense that it is coming; the mugginess of the sky seems to permeate the entirety of the painting.

Despite the attention that Giorgione paid to setting a stage for his characters to walk upon, the meaning of the figures is still remarkably unclear – it is among the most analysed, and yet unanalysable, paintings in the history of art. The scene is fraught with an all-encompassing tension, almost theatrical in its scope. The artist invites the question not of what is happening, but rather of what is about to happen. Whatever meaning he intended, it remains the case that his incorporation of the landscape as an active part of the composition was deeply pioneering. Yet, ultimately, it relies on the two figures – their thoughts, their stories, their feelings – to hold the work together. The landscape had not yet come of age.

“While Giorgione’s landscape remains a backdrop, El Greco’s masterpiece sublimely brings the background to the foreground”

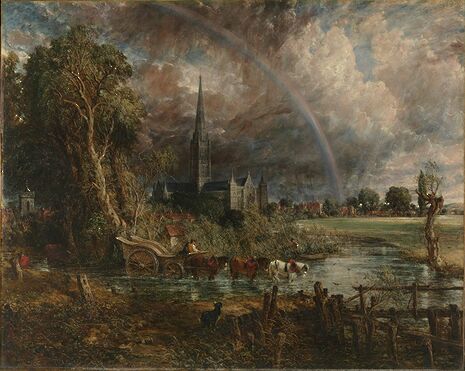

It took another century for the form to develop into something truly original, when in the relative backwater of Toledo, some miles south of Madrid, a largely unknown Greek immigrant was at work on a breathtakingly new style of landscape. The painting was El Greco’s View of Toledo. In comparison to Giorgione’s work, it looks like the clouds have given way; they stand in a dark sky, monumentally oppressive. The buildings are depicted in a remarkably modern, stylised manner; despite being so distant from the viewpoint, they nonetheless command awed attention. This is, perhaps, the difference in the emphasis of the works – while Giorgione’s landscape remains, in some sense, a backdrop, El Greco’s masterpiece sublimely brings the background to the foreground.

In his time, El Greco was largely misunderstood. Critics referred to his artistic efforts as “contemptible”, “ridiculous” and “worthy of scorn”. Travelling a quite different road to the highway of the Baroque, he was largely forgotten for three centuries. However, his time eventually came. Upon his rediscovery around the turn of the twentieth century he was lauded as a predecessor of Impressionism, and indeed there is certainly something modern in his tendency towards emotion rather than realistic detail. It gives the impression of a thousand commingling human lives, without focusing on anything specific.

The greatest landscapes do not shy away from the achievements of mankind, whether they are great cities or tilled fields. In some sense, removing human figures makes the impact of humanity only clearer. The slow shift from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, from the veneration of the individual to the glorification of society as a whole, bubbles behind the early development of the landscape.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

In viewing Cambridge from a distance, it becomes depersonalised. One can pick out the biggest buildings, but mostly each blurs into the next. It is timeless, seemingly devoid of individual lives, and simultaneously calming and terrifying to realise that the setting of one’s entire degree, all the pleasures and the pains, can be blotted out with one hand. The city is, nevertheless, infinitely bigger than every one of us. Cambridge has seen the Renaissance, it has seen the Enlightenment, it has seen romanticism and all that has come after. While their lives were very different, students of each of these ages have, no doubt, come to this spot to look upon their city. It is in itself a work of art. While the view has been much the same down the centuries, it means something different to each generation

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026