The distinct art of video games

Roger Ebert famously said that video games cannot be art, but Connor Rowlett is unconvinced that the moral dilemmas, strong aesthetics, and interactivity of games can be swept away so easily

“Video games” once said highly-regarded film critic Roger Ebert, “can never be art.” Such is the title of a blog post he wrote some years ago. His reasoning, more or less, is thus: you can ‘win’ a game in a way you cannot with art; art should be experienced whereas games have “rules, points, objectives, and an outcome”.

But this is a throwaway argument. It’s an outdated comment made by a man who has perhaps always mistrusted but never understood this new but incredibly valid form of expression. Without wading into the debate on how we define art – for that is another issue entirely – we may say it has something to do with appealing to nature, human or otherwise. It stirs something within us. It is literature, paintings, film scenes, drama. Surely a genre which incorporates all of these deserves to finally be recognised under the same title.

“It is often the case that the most ‘fun’ things to do in the game involve experimenting with one’s own dark side in a truly cathartic way”

Like all art, there is good and bad. Few would assert that the film Sharknado is a work of majestic subtlety which speaks on a profound level about our rawest emotions; equally, few make the claim that FIFA 18 fundamentally alters our contemporary worldview. Of course, this will not stop it becoming one of the best-selling games of the year – but it does stop it being considered as a masterpiece of its genre.

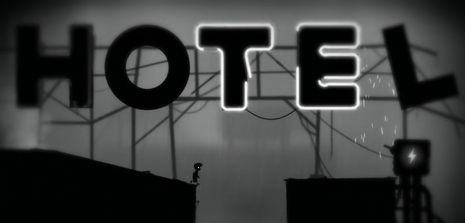

So what makes a video game artful? Perhaps the foremost element to consider is the graphics themselves. Photorealistic graphics are often lauded for their accurate depictions of a bloodied battlefields or sprawling cities. But perhaps more praise is due to games which decide to abandon this in favour of an original art style: Limbo, with its darkly menacing landscape, creates its atmosphere without appealing to reality; equally, Fez achieved something unique with its voxel-based, sculpted style, combined with the delightfully inventive rotation mechanic.

One of my favourite examples is Dust: An Elysian Tail, the labour of love of Dean Dodrill, who essentially built the game from top to bottom. His background as an artist manifests itself in the painstakingly hand-drawn graphics. Playing the game is a fantastical pilgrimage, a wholesome and enchanting experience. Modern games, particularly ones by small studios or even individuals, are increasingly embracing this impressionistic, mimetic art style; this is what Michael Davis describes as “a framing of reality that announces that what is contained within the frame is not simply real”. It is an evolution which has an echo in artwork of the past: there’s no reason why we cannot liken the tendency to stray from (photo)realism in video game graphics to the same transition towards impressionism which occurred in painted art in the 1870s.

Outside of visual style, the degree of artfulness in a video game must always be constrained by one rule which its closest neighbour, film, does not always have to abide by: it must be fun. A film may make for uncomfortable viewing or even revile the viewer; however, the spectator of a film permits this from the medium as long as the end product is great art. This is not so with the gamer. A game must always posit itself as something to be played for enjoyment and interacted with. For this, clearly, it must be essentially quite fun, and if it does not achieve this it will fail.

A fantastic example of a game which yoked this into moral conundrum is Bethesda Softworks’s Fallout 3 (2008). The game is situated in post-apocalyptia where you emerge as a wanderer, allowed – or condemned? – to forge your path in any way you please. Fallout 3’s genius is not just the essential freedom in roaming across what was Washington DC, but the moral conflict created by witnessing a world where the most heroic and debased acts are committed side-by-side, and there is no repercussion for throwing the moral compass out the window. Whatever you do, the game will not judge you, save for a ‘karma’ scale which quantifies the merit or severity of your adventures and atrocities.

It is often the case that the most ‘fun’ things to do in the game involve experimenting with one’s own dark side in a truly cathartic way. It’s something that engages the gamer to a degree that a book or a film can often only glimpse at. You might identify with characters in these mediums, but they will eternally seem external, ‘other’, not you – ultimately the most profound exploration of human nature will always come from self-reflection and experimentation, which Fallout 3 permits in its eternal neutrality: as disinterested and lawless as the vast nuclear plateau of the game’s Capital Wasteland.

Like any form of media which is created and consumed, video games are art. And contrary to Ebert’s assertion that by their very nature – i.e. being interactive – they disqualify themselves from that title, it seems far more likely that the opposite is true. A gamer is not just a spectator, but also a painter of the (virtual) reality around them. They are instead invited to take a step into the picture and be alive in it, adding a few of their own signature brush strokes. Is there any other art form which can claim to offer the same?

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025