Thoughts on Hernan Bas: Cambridge Living

Despite some initial misgivings, Blanca Schofield-Legorburo is impressed by Bas’s emotive and experimental take on traditional Cambridge lore

About two weeks before my matriculation into hectic Cambridge University life, I was searching for a final few exhibitions to go to with my mother when I found a surprisingly coincidental event occurring at Victoria Miro Mayfair: Hernan Bas’s Cambridge Living exhibition. I read a brief introduction and looked at the sample works on the website, surmising that Bas had been a resident artist in Jesus College in 2016, where he had spent time researching the institution’s history, literature and mysteries, including the ‘Night Climbers of Cambridge’ which very much inspired this set of works.

Being an incoming Jesuan, I established a date for attending, without much more enquiry into the artist’s style or repute. As I had never heard of Hernan Bas before, I unabashedly expected to turn up and frown at paintings of traditional white Cambridge boys doing traditional Cambridge things, criticise the usual lack of female representation, and call it a day.

“This exhibition was the opposite of a straight-jacketed introduction to the haughty Cambridge experience”

What I encountered, however, was an extremely well thought out and thought-provoking exhibition. The space was divided into three rooms, with a larger one at the entrance and two smaller ones at the back. The first was taken up by larger paintings depicting boys engaging in activities such as night climbing, punting and swimming in the Cam. These paintings when viewed in person are striking in two ways.

Firstly, Bas experimented with home-made paints from pigments, which he became “slightly obsessed with… after seeing the Fitzwilliam show [of illuminated manuscripts]”. This, along with his use of various textures for materials such as college roofs, clothes and skies, and heightened folklore colours, ensure that what could have been a rather 2-dimensional side perspective of a boy’s activity becomes many-layered, both technically and, as I will elaborate on, spiritually.

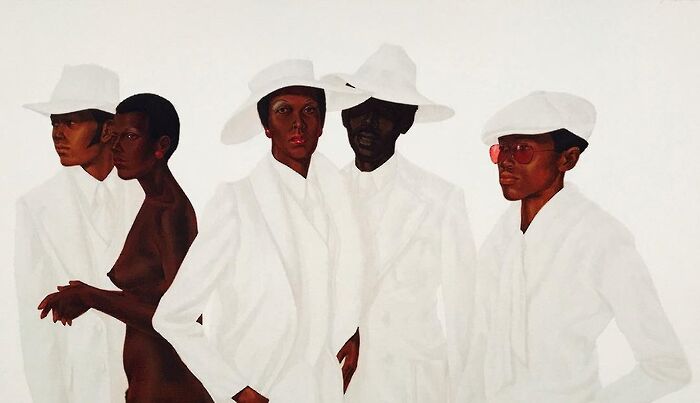

Secondly, Bas’s use of awkward physical stances and lost facial expressions, in contrast to the established structure of the Cambridge scenery, offers a new perspective into how challenging coming of age is in a world where the masculine identity continues to be constrained. Far from simply painting white Cambridge boys doing traditional Cambridge things, Hernan Bas was continuing in his exploration of the theme he calls “fag limbo”. He explained this term in a 2011 interview with Art21 Magazine, saying that “the whole idea of fag limbo to me begins with a character or an identity that doesn’t quite fit the clichés that one would expect for a young homosexual character. I wasn’t necessarily the young, flamboyant gay – I didn’t fit that cliché, but I didn’t fit the male, straight-boy cliché either. I always felt like I was sort of in the middle and not quite sure what to identify with.”

“All physicality displayed seems uncomfortable and desperate in this conservative space”

The 1930s Cambridge setting is very effective in emphasising this self-uncertainty. All physicality displayed seems uncomfortable and desperate in this conservative space: boys attempting to scale buildings, fleeing rigidity, gripping pipes with all their might (as in Nightclimber (Drain Pipe Method)), or, alternatively, awkwardly sitting in a punt, arms defensively held against the chest with one hand in a box filled with swans in Charon of the River Cam (Slain Swans). Their countenances emphasise this desperation, with the majority of them in either deep confusion, Bas having painted the brows lowered into a grimace, or with a searching gaze, eyes wide, blank and sad. Moreover, where the paintings contained more than one subject, their relationship always appeared to be one of dependence, with one punting or accompanying another in a climb. Yet, ultimately, the deep detachment prevailed in far removed expressions.

The second room contained the last of the works from the Cambridge Living series. After seeing the Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist at the Art Institute of Chicago, Bas went “mad with making ink transfer drawings”. These works are examples of this, smaller than the paintings and monochrome, with only black and white shades. Here, the artist explored the concept of ‘freshers’, a term which he had never heard of before going to Jesus, displaying them in various stages of study in small college rooms. What is interesting is that the students seem to be disinterested in their work, with laid-back poses and bottles of wine, choosing a search of self over the Cambridge study frenzy.

This room also contained pieces of night-climbing, including the most poignant work for me, Rooftop Runner. In this, the boy is finally free from physical constraints and runs through the apex of a roof, yet still with emotional restraints, seen in the doubting frown while looking down.

Bas did employ one colour in this collection of ink work: in a piece of a boy drinking out of a cup containing a goldfish, the fish was given its orange hues. This could perhaps be a humorous touch, but I see it as symbolic in that they are both isolated and misunderstood.

This exhibition was a perfect example of how art and images can highlight something so difficult to enunciate. For me, it was also eye-opening in that I discovered an artist who I really admire and respect; and also that I am still affected by prejudices, as shown by my initial reaction to the brief introduction I had read. This exhibition was the opposite of a straight-jacketed introduction to the haughty Cambridge experience I had imagined it would be. It is an illustration of an important polemic that is still rarely openly discussed and which is important to remember as we embark on a journey in an institution that Hernan Bas said he had been “lucky to take part in”, but that also had “startlingly present” privilege.

The exhibit is on until 21 October 2017 at the Victoria Miro Mayfair gallery in London

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025