Different subjects: anatomy of an artist

The study of anatomy and practice of art are in many ways symbiotic; Sofia Weiss discusses how her study of medicine has experienced similar benefit from an appreciation of art

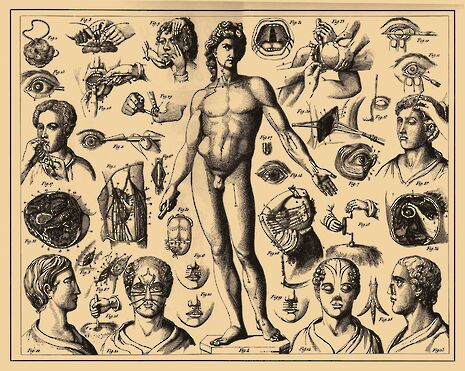

Every year I move into a new college room and every year I drape posters of human anatomy across my walls with pride. This year, I even painted some myself. It wasn’t until doing so, however, that I began to appreciate these images for what they truly were: not simply pixels of scientific information, but works of art. In fact, to understand the artistic roots of anatomy, I found myself vicariously travelling to Renaissance Italy, for it is often overlooked that to be an artist during this period was, for many, to be an anatomist.

“I am transported back to my first patient, and one of the most enduringly intimate relationships I have developed”

As European art turned towards more life-like portrayals of the human body, the relationship between artist and physician became one of symbiosis; in exacting the human form in their creations, artists required a deeper understanding of how the structures of the body worked together, and not only those immediately visible. Thus, the dissection room became a second home for Da Vinci and those of his ilk, a sanctum in which to produce images of the body that combined medical knowledge and an artistic vision of humanity’s place in the world.

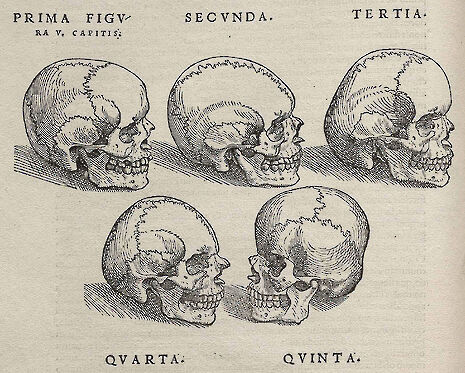

Both disciplines were to benefit from this marriage. From a medical perspective - and to their enormous credit - Renaissance artists pioneered a consistent vocabulary of anatomical illustration with which new discoveries could be precisely recorded. These pieces present both a developing scientific narrative and a deliberate, singular beauty as some of the seminal oeuvres of their time. Particularly striking is Andreas Vesalius’s magnum opus, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body). Some of the most unforgettable images from this body of work are those known as the Muscle Men, depicting the human form in progressive states of dissection amid the natural landscape of what is presumed to be the Eugenean hills near Venice and Padua, Italy. If merged together, the pictures form a continuous panorama, placing humans firmly in the natural world despite the seemingly detached scientific investigation of their bodies.

As a medical student beholding these, it is impossible not to find myself considering the material that makes the man far beyond simply physical structures. I am transported back to my first patient, and one of the most enduringly intimate relationships I have developed. When I intensely studied their corpse in first year, I became acquainted with the contours of their muscles and the idiosyncrasies of their nerves; an expert on the now defunct vessels through which molten vitality once coursed. The disposition of this human being, however, was and will remain largely unbeknownst to me. I will never hear recounted their fond anecdotes of youth, or witness expressions emergent from a face with which I am otherwise familiar; I can only imagine their natural context. Thus, through the artwork I am reminded of my personal position as not merely a haphazard mechanic of the flesh, but a student of what it means to be human, in all its fragility and impermanence.

Indeed, perhaps the most iconic image from Fabrica is that of a skeleton leaning carefully on a plinth and contemplating a skull beneath its right hand. Much of art’s allure lies in its ambiguity; we each find in a piece answers to questions we didn’t even know we were asking. Herein, I intepret a metaphor for the contemplation of death, which ironically is what gives life to the art of dissection itself. After all, we build our knowledge of a living system from its cadaveric remains. Alongside the figures of Vanitas and ‘memento mori’, such works provide a route into dealing with the more philosophical aspects of the medical trade, by stressing the need to hold acutely present our own mortality, and the inevitability of death. Even as medical students in 2017 this proves difficult – we are, after all, taught how to cure – and it is often necessary to remind ourselves that as doctors, we will ultimately have a 100% failure rate.

Cambridge Medics, myself included, are taught to refer to our anatomy course as ‘FAB’, an acronym that to my mind, serves two purposes. One, is to be the butt of many a clichéd joke – ‘anatomy is fab – get it?!’ and the like. The second, is to remind us of the art in our discipline. FAB stands for Functional Architecture of the Body, because that is what we are: constructions of nature, understood because of artists as much as physicians. In this context, and no matter how at risk of a further cliché I may be, I would venture to suggest that anatomy is actually fabulous, with the breadth and depth of its wonder available only to those who observe it with more than a purely scientific eye

News / Cambridge launches plan to bridge ‘town and gown’ divide27 October 2025

News / Cambridge launches plan to bridge ‘town and gown’ divide27 October 2025 Arts / Reflections on the Booker Prize 202528 October 2025

Arts / Reflections on the Booker Prize 202528 October 2025 News / SU referendums heat up as campaigners claim intervention29 October 2025

News / SU referendums heat up as campaigners claim intervention29 October 2025 News / Students launch women’s society excluding trans women31 October 2025

News / Students launch women’s society excluding trans women31 October 2025 News / College rowing captains narrowly vote to exclude trans women31 October 2025

News / College rowing captains narrowly vote to exclude trans women31 October 2025