‘The creation of fakes is not a criminal act’: is authenticity everything?

In the wake of a recent art scandal, Blanca Schofield-Legorburo wonders if forgery has some unexpected upsides

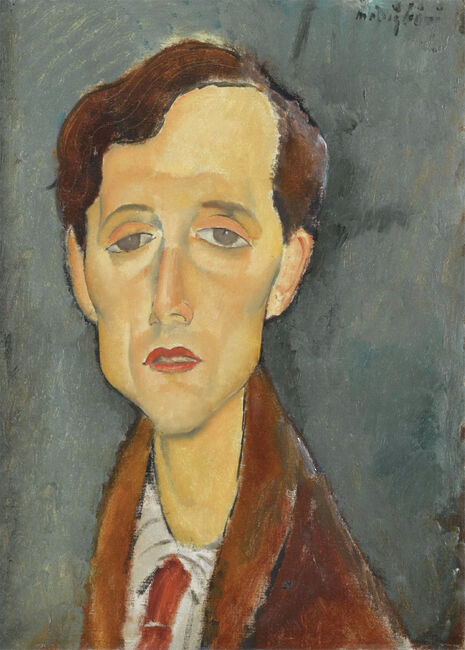

During a recent visit to Italy, I went to what I would have described as one of the most moving art exhibitions I have attended: Modigliani in Genoa’s Palazzo Ducale.

Up until then, I had not had much exposure to the work of Amedeo Modigliani (known to friends as “Maudit”, for wretched). Yet I was captivated by the emphasis the curators had put on his intense relationships with women, from the selective detail of eyes, used only when he had truly connected with the subject of a portrait, to his Lying Nude, bursting with colour, which had allegedly been taken down by police for portraying pubic hair. After leaving, I persisted in my addiction to buying postcards, adding a record seven to my collection, a sign of how blown away I had been by what I saw.

“Why is it that many in the art world show so much interest in abolishing fakes? Is it to preserve the reputation and style of the artist? Or simply to ensure the value of the originals?”

Then, a month later, my friend who I’d travelled with sent me an article she had read in France about this exhibition: it had been prematurely shut down as over a third of the paintings were suspected as fakes, and the curators were being questioned. Carlo Pepi, the 79-year-old art critic who had first questioned them announced: “These were missing the three-dimensional elegance of Modigliani […] even a child could see these were crude fakes.” I was taken aback and started doubting my enjoyment: was it still legitimate?

Since that frightful discovery, I have comforted myself with the knowledge that about 100,000 people attended the show before any doubt was raised. Moreover, the fake Modigliani industry is not fresh news. In 2012, an old Modigliani scholar, Christian Parisot, was arrested on several accounts of forgery, including 59 works which he had falsely attributed to the artist. According to many experts, Modiglianis are notoriously tricky for proving authenticity. The director of ArtBasel, Marc Spiegler went as far as saying: “The drama here is that I could find a Modigliani in an attic tomorrow, with a letter from Modigliani still attached to it, and people would still hesitate.” This difficulty aligns with what Cambridge senior forensic archaeologist, Dr Christos Tsirogiannis, thinks of the strength of the fight against forgery: “Everybody claims that they care about abolishing fakes from the market and collections. However, only a few really try to detect them and even fewer have the expertise to do so. Tests of all kinds may take place, but forgers are always at least one step ahead, to pass them successfully.”

Why is it that many in the art world show so much interest in abolishing fakes? Is it to preserve the reputation and style of the artist? Or simply to ensure the value of the originals? Perhaps fakes actually enhance the understanding of, and exposure to, a particular artist. As Blake Gopnik of the New York Times said, “If a fake is good enough to fool experts, then it’s good enough to give the rest of us pleasure, even insight.” Fakes have been so widespread since the beginning of art that Damien Hirst even questioned the importance of what we consider as true or real art in his Venice exhibition, Treasures from the Wreck of Unbelievable. Sculptures made by him, which were described as being from ancient civilisations, were rusted and covered in what looked like coral from supposedly having been in the sea for centuries, so as to confuse the viewer and force a conversation about what makes art legitimate.

There is also the controversial question of appropriation of famous art through mass printing or use on everyday items, which some deem as another way of promoting inauthenticity. The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones wrote: “We must rescue Van Gogh from becoming a pop culture cliché”. This is a view that is gaining supporters as art becomes branded; many were shocked by the Louis Vuitton and Jeff Koons collaboration in The Masters bag series, made up of bags plastered with works by Van Gogh and Da Vinci, as the phrases 'knock-off' and 'kitsc' were thrown around on various social media platforms. Yet some were more forgiving, and propagated the view that it would be good to humanise and allow freer movement of art; Jo Ellison of The Financial Times opined that the Mona Lisa looked: “a little more liberated away from her bulletproof shield at the Louvre”. However, it is hard to view this fashion experiment as a step forward towards accessible art for the public when the cheapest bag is $400.

Ultimately, artists can be misrepresented in forgery, as Pepi insists Modigliani was in this case, saying: “Poor Modigliani, to attribute to him these ugly abominations”, and there is a lack of transparency and honesty to the audience. However, in my view, the creation of fakes is not a criminal act. They, along with their 'kitsch' counterpart, do combat the elitism of the modern art world through providing this broader access and insight, while also introducing the work of new anonymous artists and posing the everlasting questions of what art really is and what is important in the enjoyment of it. I may not possess the keen eye to know which pieces were truly Modigliani’s, or the name and origins of the other artist whose work I was admiring, but, at the end of the day, I still very much enjoyed the experience and am glad with my glance into the wider world of Maudit

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 Features / Is the ‘voiage’ worth it? 3 March 2026

Features / Is the ‘voiage’ worth it? 3 March 2026 Interviews / Author and self-acceptance advocate Ro Mitchell: ‘There’s no shame in liking yourself’4 March 2026

Interviews / Author and self-acceptance advocate Ro Mitchell: ‘There’s no shame in liking yourself’4 March 2026