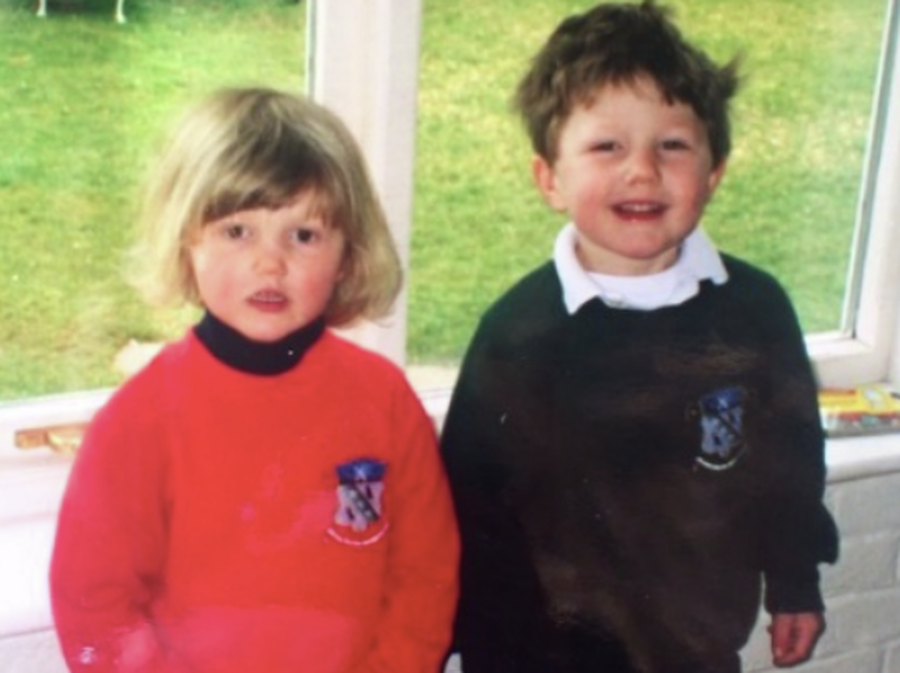

Mary and my grandpa’s funeral

You can be sad, but you also have to let go, as Holly Platt-Higgins learnt in two very different ways

My grandpa died quite a long time ago; I think I was about eight. I don’t remember much about him, just small things – he used to bring us Kit-Kats and Eckels Cakes when he came to visit. He worked on trains and bought me Winne-the-Pooh books every Christmas. He lived by the sea-side with a little dog called Lucy and he liked a pub called The Mermaid. And, I’ve just realised, no one ever called him by his name. I don’t think I know his name; everyone just called him ‘Gywn-Baby.’ But, Gwyn can’t have been his name, because that’s my mother’s maiden name. He can’t have been called Gywn Gwyn-Williams. But, maybe he was? I don’t know.

Despite not remembering him very clearly, my grandpa’s funeral is a distinct memory of mine. The six of us pulled up, in the old Volvo, onto a little pavement slope outside the church. I looked through the window screen; uncles, aunts, cousins, everyone I knew as a person, standing about, sort of awkwardly, in black, not being a person at all.

With four children and the maximum age gap between any of us being two years, my parents would often have instructive conversations with us before leaving a vehicle and entering any event; they still do. These were to ensure people thought we were a normal, functioning family and to avoid any tantrums/incidents which would make my parents look like bad parents. They were relatively standardised pep-talks: no grizzling; do not wind each other up; be nice to the other children; look people in the eye and say please and thank you; try not to break anything; remember to flush the lavatory; do not go outside without your shoes on, and so on. But, this briefing was different. My father switched the car engine off, there was a pause, and my mother turned back from the front seat. Pink lipstick like always, her face came into focus as everything else blurred into the blackness behind her. She smiled at us and said, “Alright chaps, no crying, okay?”

“You’re allowed to be sad when you lose someone or something, but you’re not allowed to wallow”

That was the rule, no crying.

We all filed into the church. My uncles carried the coffin in and the organ played. Mostly because I was an overwhelmed child, rather than somebody really suffering, a familiar fizzing feeling crept into my nose and my eyes began to water. I looked up at the ceiling to stop the tears from falling out and noticed the beams on the church roof. I counted them backwards, following each one with my eyes. I passed a lot of the time just counting the beams backwards, until the tears had fallen back inside; very careful not to blink, in case one crept out of the corner.

My uncle was telling a story about Grandpa getting furious with everyone on Saturdays. Grandpa would buy bread for lunch and leave it on the kitchen worktop. Throughout the morning, every hungry hand going through the kitchen thought to just break a little of the crust off as they went by. Eventually, there was nothing left for lunch. My uncle said he wondered why Grandpa never thought to buy two loaves, because this happened every weekend.

I enjoyed the story and looked up at my mother, I suppose to check if she did too, and she was sort of laughing and sort of crying and it was very strange. She was breaking the rule, but I sort of understood that she was allowed to. I hadn’t really realised before then, that she was somebody’s child before I was hers and when I did, I held her hand.

Many years later, I was going through a Nabokov phase. I’d read Lolita, ordained it as my favourite book and then decided to read his other works. Among them I came across Mary, a short novel about lost love. Unsurprisingly, it never gained much attention in the shadow of Lolita and Pale Fire but it was a satisfying book that I think taught me a lot about loss, more than Grandpa’s funeral did.

Mary follows Officer Ganin, as he moves to a boarding house in Berlin, having been displaced by the Russian Revolution. Although there are many sub-plots, the principle focus of the book is Mary. She is Ganin’s first love who now, coincidentally, happens to be married to his neighbour in the boarding house. Unable to let another man have her and nostalgic for the love once shared between them, Ganin plans to reunite with Mary and run away together.

This does not happen. I will not disclose, for those of you looking to read the book, why this is the case. But, Ganin’s acceptance of this ending is what made the book important for me. Mary encouraged me to learn to let go gracefully of the things not meant for me.

There is a beautiful moment in the book when Ganin stands on a train station and recognises that holding onto the memory of Mary has not brought her any closer to him, “other than that image no Mary existed, nor could exist”.

Only when Ganin realises that he cannot pull his past into his present, is he relived, “in that sober light, the world of memories in which Ganin had dwelt became what it was in reality: the distant past”. We cannot drag the things or people who have left us alongside, no matter how much we’d like them to accompany us. Mary explains that letting go is not the same as forgetting and you have to let go of that which has already left you.

My grandpa’s funeral didn’t come up in conversation until recently. I told my mum about the car, about the ‘no crying rule’, about the beams. “Oh God darling, that’s not what I meant! I just meant no howling or rolling on the floor of the church. Of course, you were allowed to bloody cry.”

That makes much more sense now. Obviously, that’s what she would have meant.

Although it was something Nabokov told me, I think my mother meant to say the same thing. That you’re allowed to be sad when you lose someone or something, but you’re not allowed to wallow. You can cry, but you can’t howl on the church floor.

After writing this article, I asked my mother. His name was Gywn. Gwyn Gywn-Williams