Existential crisis, hate letters, and The Outsider

Holly Platt-Higgins reveals how two completely different sources have taught her to live life for the moment

The Outsider, by Albert Camus, is one of the most important French novels ever published. The first line reads simply ‘Mother died today'; the rest of the novel observes how the title character Meursault continues to exist after this incident.

Unsurprisingly, Meursault is something of an outsider; the blurb of my copy notes that ‘he seems to lack the basic emotions and reactions’. The Outsider is a book that I was totally enamoured with and one that I definitely didn’t comprehend completely. (I think it might be the kind that you have to read a couple of times to actually understand, rather than just think you’ve understood.) I’m not about to insult Camus or those of you who have read it, by trying to offer a summary or a review. But, if you haven’t read it – you should, it’s really worth it.

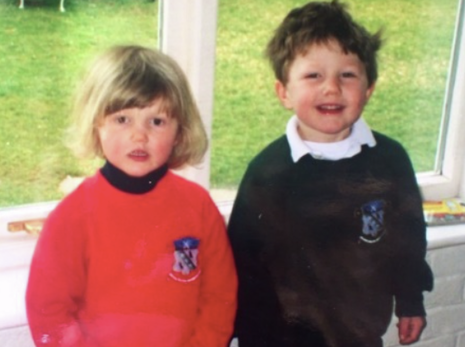

When I was reading The Outsider this summer – I thought about my brother. My toast may always land buttered side down but, my older brother has an amazing capacity for landing on his feet. Apart from going through a slightly ginger phase at about 15, things have always worked out quite nicely for him. Growing up he was something of a reprobate.

He never had any money; most Friday nights he’d be borrowing a fiver from me to ‘grab a pint with the boys at the pub’. He never did any schoolwork - I don’t mean like one of those people who pretend not to be working, but have actually been secretly swatting away for months in a dirty-cup infested cave. I mean he did no work; my parents physically locked him in the dining room for quite a while, and when that didn’t work, my father took up ‘supervising’ to make sure he was revising and not just lying on the floor, stoned, playing with the dog. My parents spent most of my brother’s childhood miserably telling friends and relatives who asked after him, ‘he just sits in his pants, on Facebook, all the time.’

It wasn’t just that my brother had a liberal attitude towards working, it’s that he would steal your belongings (and subsequently break them), eat food that he knew wasn’t his, smoke your cigarettes, take your phone charger, steal someone’s cat, steal the village sign, hit golf balls through the neighbour’s window, take essential kitchen items (like the only tin-opener) and then leave on a random fishing trip for a week. He’d forget to pick you up from a party, forget to buy you a Christmas present and, most annoyingly of all, he’d always duck the consequences. He is disgustingly charming and funny. This, I think, must be my brother’s approach to avoiding all repercussions – get people to laugh. It was always a highly effective technique; although people were constantly frustrated with him, everyone still liked him more than they wanted to; everyone let him get away with it. Apart from one person…

It turns out, unbeknown to my brother, my granny was not thrilled with his approach to life or his managing to get away with it. (This was about to be the stuff of childhood legend.) The Hate Letter of 2013 – it was an exciting time in the Platt-Higgins household. The letter contained some vicious content about my brother needing to join the army to learn some discipline; about him being a disappointment to the family; about my ‘poor parents’ having to deal with him. I can’t say what else was in the letter; because my brother burnt it. He didn’t bother reading all four pages, he just set it on fire and threw it out of his bedroom window. He didn’t really speak about it either (we were all slightly worried that he was having some sort of existential crisis as a result) but when Ma inquired as to whether he was OK, he earnestly replied that he ‘genuinely didn’t care’. And he didn’t.

"Camus and my brother both told me that nothing matters much – not in a depressive, I-listen-to-Fall-Out-Boy kind of way, but in kind of a liberating way"

While The Outsider has nothing to do with hate letters or complacent teenagers who won’t revise for their exams, it does consider existential crisis and spends a considerable amount of time weighing up what’s important and what isn’t; this is something my brother was excellent at. I always admired, with a slight envy, his totally carefree approach: ‘What’s the worst that can happen?’ he says as he steals something; ‘Why bother worrying?’ he asks you, flicking a cig butt out of the doorway, ‘Shall I do it?’ He calls down to you, just before he jumps out of the top floor window to see if he’d break his leg – he didn’t. Unlike me, who still often loses sight of any rational thought, rehearses how I’ll vocalise my order when the waiter asks, won’t attend any function unless someone I know is going, has to flick the light switches in certain way before I leave my bedroom, picks socks dependent on what day I think it’s going to be – and an array of other weird and pointless things – my brother and Meursault never bothered to waste their time.

And the thing is, when I came back from summer, having read The Outsider, my brother had graduated from university with a 2.1. He told me he had a job as an accountant that started in September. He now has a girlfriend, who lives in Putney; she works in marketing and they go cushion shopping at the weekend, because she likes cushions. He has a dog and a car. He’s looking to buy a house. He listens to the news. He doesn’t ask me for money to go to the pub anymore. He’s quit smoking.

My parents quite often told me not to be like my brother. They never told me it wasn’t going to make any difference – ‘one might fire or not fire, it would come to absolutely the same thing’ - we’d end up in much the same place, him just having had worried a lot less about getting there. Camus and my brother both told me that nothing matters much – not in a depressive, I-listen-to-Fall-Out-Boy kind of way, but in kind of a liberating way.

"From the dark horizon of my future a sort of slow persistent breeze had been blowing towards me, all my life long, from the years that were to come."

I don’t think either Camus or I are advocating a belief in destiny, and I’ve recently learned not to engage in conversations about free will, but what I will say, especially to Cambridge students, is, relax. Enjoy it a bit more. You’re here and you’re young, so don’t ruin it for yourself by worrying