The Crucible

Shounok Chatterjee is engrossed and entranced

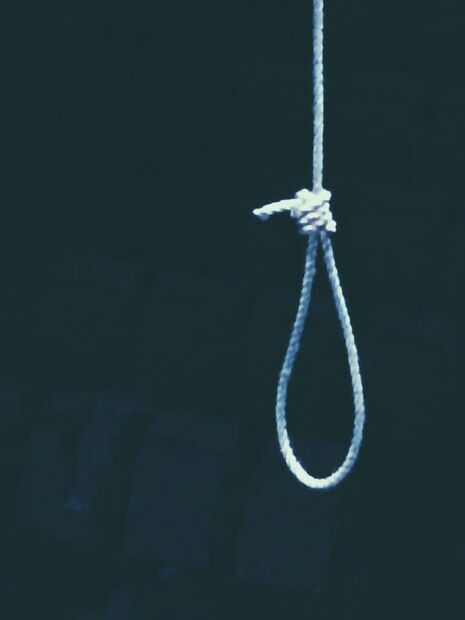

The prophetic words of Elizabeth Proctor "the noose is up, the noose is up" in the second act are made flesh. A noose looms ominously over the sparse black space indicating the stage. I am a little uneasy at first, the minimalist set smacks of a suspect intent to tamper with one of my favourite plays. Arthur Miller’s classic was first performed in 1953 against the backdrop of the ever expanding inquiries of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He was obviously trying to show the parallels between puritanical, colonial Salem, Massachusetts in the late seventeenth century thrown into the midst of paranoia and fear during the witch trials, and that other intolerant period. Fitztheatre’s new adaptation of this canonical work strips away the concrete trappings of the 16th century; gone are the colonial manners and period costumes. The idea is to expose the basic and constant logic of fear that corrodes human empathy for others, propelling the protagonists to the inevitable violence we are reminded to expect.

But the truth is it is in the moments where the most obvious liberties are taken with the text that the play is at its engrossing best. The opening sequence is a particularly good example. It features the ever present gothic soundtrack and stylised mime to represent the occult scene of orgiastic dancing and pagan ritual that sets off the events of the play. It is a haunting mix of choreographed movement and light. The Crucible is on the whole an auspicious debut for directors Michael Tigchelaar and Rebecca Vaa. Another example of exquisitely planned and effective physicality is the court scene where Mary Warren is turned on by the other girls and they see the devil in her. If only we could have seen more of the entrancing physicality that Ellen McGrath and others brought to their portrayal of the possessed girls of Salem town. At the same time the many altercations in the play are not as consummately embodied. Too often characters are left shouting entire lines millimetres from each other’s faces with little room to move. I don’t think anyone argues like that, not least with people you strongly dislike. Another decision that puzzled was the Dickensian caricature of Judge Danforth and Hawthorn, the latter featuring a walking stick and wig-especially, especially in light of the decision to pare back all other period affectations like accents and naturalistic sets.

Joanna Clarke is mesmerising as Elizabeth from the beginning. She reminds me of the woman in Millet’s Angelus. Hair wound unforgivingly in a tight bun, wearing an austere grey skirt and clutching a shawl, she is the picture of quiet and ambiguous dutifulness, upright and vulnerable at the same time. Charlie Clark, the costume designer, has an instinct for the richly evocative. Elizabeth’s resentment towards her unfaithful husband is sketched in an understated manner at first: pursed lips, closed arms and the deliciously delivered reproach "I see what I see". So when Clarke abandons Elizabeth’s saintliness in the final scenes and breaks down, "it were a cold house I kept", it is deeply affecting. Ronald Prokes as her imperfect husband Proctor has a rich and resonant voice and comes into his own in the second half. Prokes owns the stage for the final few scenes and maps with heartrending conviction the progress of his character from resignation to save his life and blemish his soul, to his last stand to protect his "good name".

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026