The Beekeeper of Aleppo: an uneven tale of family grief and displacement

Despite an important story and powerful production value, the script fails to truly capture the emotional urgency of the source material

The stage adaptation of Christy Lefteri’s book The Beekeeper of Aleppo sees a man, Nuri, and his family forced to flee their idyllic livelihood and beekeeping farm due to war in Syria, and make the precarious journey to England to claim asylum. This production at the Cambridge Arts Theatre renders a powerful story of family, grief, and trauma but doesn’t entirely capture the emotion of its subject matter.

The plot is a journey spanning borders: it oscillates between the characters’ past lives in Syria and their experience in the present day, in a British asylum camp. From a harmonious, richly-evoked family life in Aleppo, the family is forced out of their homes and encounter a system of condescending bureaucracy that immediately sees them as criminals who must prove their innocence, alternately prying at and disregarding their trauma. While transitions were made clear through sound and lighting choices, it was perhaps too apparent that the play was adapting a novel. Monologues to the audience as a means of conveying narrative often felt like heavy-handed exposition where they could have benefitted from a subtler approach to storytelling, or conveyed more sense of Nuri’s internal consciousness rather than relaying the plot to us.

“Sound and lighting dramatically conveyed the haunting aftermath of trauma”

The first half, introducing us to a vignette of family life and following its plunge into danger, tended to paint big emotions with bold strokes yet crude colours. I wanted to feel moved earlier on, but found that the writing sometimes lacked specificity and relied on vague, emotionally bland dialogue. The second half, however, developed a much needed complexity to the narrative and characters, resulting in an interesting and welcome twist that displayed the illusive and dissociative nature of grief. The script’s occasional comedy was well-received by the audience and helped to create warmth in an otherwise harrowing story. Furthermore, the shifting of Nuri’s expositional monologues into the format of correspondence with his father was much more effective and natural in conveying the plot: we could believe in Nuri’s poignant relationship with his father, which gave the exposition a greater sense of desperate emotional urgency.

“The play captured a strong sense of bonds between characters”

The play captured a strong sense of bonds between characters, especially the father-son relationship in the story, which develops long-distance throughout. Roxy Faridany gives a strong, tender performance as Afra, Nuri’s wife, who, physically blinded by the trauma of her son’s death, sees her husband gradually slipping away from her. Aram Mardourian’s Nuri held the play’s centre together as a strong, yet troubled, father often degraded by the dehumanising process of seeking asylum. The final conversation between Nuri and Afra carried an intimate poignancy that showed the production at its best. Though his character felt depicted at times like an everyman, more concerned with being a broadly relatable than specific, Nuri’s development into a somewhat morally grey man paralysed by guilt and shame fashioned him into an unreliable narrator who I nonetheless rooted for. This development was refreshing: refugees are so constantly reduced and objectified on our news screens, and the subjectivity and ability to narrate one’s own story meant that characters were represented without being idolised or demonised.

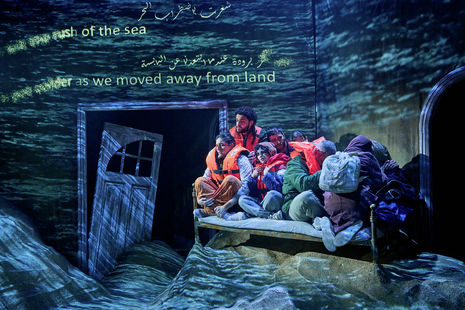

Sound and lighting dramatically conveyed the haunting aftermath of trauma in the play. The projections were extremely powerful — particularly one displaying real-life footage of destroyed Syrian cities onto the family home, which felt necessarily provocative and striking. An innovative reworking of traditional set created an apt liminal space, as chairs were strewn in amongst piles of sand. As designer Ruby Pugh notes, “a lot of the spaces in the story are homes, whether makeshift or temporary”.

Throughout the play, the positioning of the British characters as other was refreshing. It centred the stories of refugees as you felt the frustrating invasions of out-of-touch case workers. While there was some mention of politicians, this was never really a strong note: the story felt written more for the purpose of humanising a family’s story than criticising a political stance. While it felt at times as if the urgency of this timely story could have been more provocative and deliberately uncomfortable to its audience in a world rapidly stripping migrants of basic rights, the production aimed to underline the very human ways of coping with displacement. Often, above all, it revealed the rejuvenating power of the natural world in situations where humans fail in empathising with one another’s struggles.

The Beekeeper of Aleppo is showing at the Cambridge Arts Theatre from Tuesday 16th to Saturday 20th May, 7:30pm.

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026