Blood Brothers (Play Version) asks where the power is

Stanley Lawson reviews this week’s ADC mainshow, a reimagining of the popular story

Blood Brothers with hardly any music might sound like an alien concept to many familiar with the show. However, based on last night’s performance, it seems the play version of Willy Russell’s script has a potency of its own. It is, at its heart, a tracking of the loss of innocence to the degradations of the social and economic wounds inflicted on 1980s Merseyside by the Thatcher government through the lens of an improbable but curious connection between two separated twins. A further depth was added to the dynamics of power in this production by director Lucy Green casting two Black men as the brothers, both giving the production both a 21st century immediacy whilst also drawing out a long history of the intertwined forces of class and race.

“‘Where’s my power?’ rings out as the pained clarion call of the whole play”

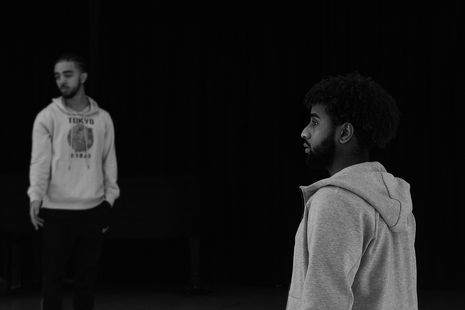

Eyoel Abebaw-Mesfin gave an infectiously exuberant performance as young Mickey and a studiously subtle performance as the adult version of the character. The descent into despair and violence of the cynical and tired adult Mickey in the second act is the volta of the play, actualising Russell’s positioning of circumstances to Abebaw-Mesfin guided the audience from the naivety of childhood to the grim social realities Russell relentlessly excavates; “Where’s my power?” rings out as the pained clarion call of the whole play. In contrast, Amin Elhassan played more into the enduring naïveté of Eddie into his adulthood of wealth and ease, as much a critique of Thatcher’s Britain as Mickey’s struggles.

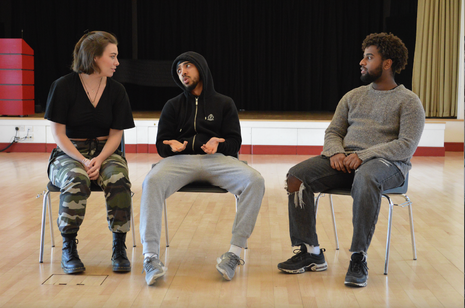

The central performances of the show held together; the trio dynamic of Eddie, Mickey and Linda (Eva Carroll) clicked, the actors bouncing off each other in both light-hearted comedy and the underlying tensions which emerge between the three. The soured childhood fraternal relationship of Mickey and Eddie, deteriorating because of Eddie’s ebullience crashing against the realities of Mickey’s life, was the dramatic centrepiece, and it was pulled off convincingly.

Abebaw-Mesfin and Elhassan gave a careful counterpoint to each other as the relationship fell apart, with Abebaw-Mesfin’s earlier adolescent bravado melting into defeat just as Elhassan had Eddie coming into his own as a confident adult in a position of power. Abebaw-Mesfin and Elhassan bounced their performances off each other with success, generally keeping the comic timing necessary to carry the sections where they are playing children. Carroll, making a strong debut in Cambridge theatre, was compelling in the second half where the character of Linda really comes into her own; Carroll’s physicality of the vivacious young women giving way to the exhausted, isolated housewife dragging shopping bags behind her was heart-wrenching. Inevitably, the rapid shift of tone in the second half of the play jars slightly, but the cast did their best to keep the audience with them as the play rushed to its conclusion. All three actors pushed the energy of the play on, shifting the tone by degrees so that the dramatic and violent end both stands in contrast to the start of the play yet does not feel too much as though it came totally from nowhere.

“This was not going to be a ‘traditional’ Blood Brothers"

The relationship between the two mothers, Mrs Johnstone (Monique Knight) and Mrs Lyons (Mia Condron-Asquith) which opens the play was strong in its most acrimonious moments. Condron-Asquith was somewhat limited by Russell’s unsubtle treatment of Mrs Lyons in the script, but the dynamic between the two was given a fresh dimension, again by Green’s casting. The power dynamic between the two women is thrown into an intersectional light in which both race and class act on Knight’s viscerally vulnerable Mrs Johnstone, who is unable to resist the coercion and bullying of Condron-Asquith’s Mrs Lyons.

The potency of the intersectional power differential between the two women was an insightful extension on Green’s part of Russell’s original social critiques and an excellent riposte to anyone who might be tempted to ask, “Why yet another staging of Blood Brothers?” The unsettled contemporary energy of the show was only augmented by Cat Salvini’s surrealist stage design, which gave away immediately this was not going to be a ‘traditional’ Blood Brothers. For what it is worth, this particular production, while not without its minor flaws, felt more relevant, impactful and grounded than any other version of the show I have ever seen.

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026