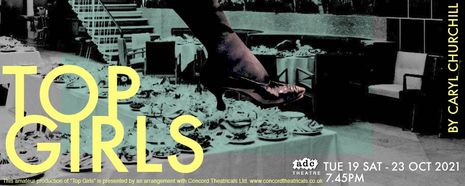

Top Girls: ‘Grounded, blunt and exposing’

Emma Robinson reviews this weeks ADC mainshow, Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls

I really thought I knew what I was getting myself in for with this one; the bio made it sound sort of odd and very feminist. And I sat down feeling safe with that.

Let’s just say, I was pretty mistaken.

Don’t get me wrong, it is definitely feminist and odd at times, but it is also quite a lot more than that. Top Girls is eccentric, but it is also grounded and blunt and exposing. It makes us look into that cavernous space between a family torn apart by their polar opposite experiences, offering us two world views about class and rights and politics, education and opportunity, which are perhaps impossible to unify. It is chaotic and cohesive and a clambering of different voices that will just talk over each other because that is the only way they can all exist in the same space.

Please don’t hear the tone of the title as the all-inclusive, hyping voice of a palatable feminist figure like say Emma Watson. Top Girls depicts the dog-eats-dog environment of a Thatcherite society, where if someone is on top it’s only because someone beneath is picking up the slack. Associate the play with that iconic woman, whose name googled alongside the word ‘feminist’ gives you as many articles about self-serving conceitedness as about momentous leadership. This play is shocking, not just surprising, and, honestly, the only aspect of this production that was anything less than amazing was the bio that undersold it.

Evidently, Molly Taylor’s direction, with the assistance of Dylan Evans and Holly Pearce, was extremely considered, as every character—and there are many—is defined and consistent even while their superficiality is being peeled or ripped off.

“The energy of overlapping conversations”

This definition of character is particularly essential for the very full stage of the opening scene, where women from across history sit down for full four course meal. This had the potential to be very static and flat. But this wasn’t the case thanks to the energy of overlapping conversations which slide seamlessly into one another, realistically depicting a dinner environment, but also more tellingly representing the competition for the audience’s attention and perhaps even recognition.

Maria Telnikoff’s comedic presence is one of the influences that elevates the scene. It is all the more brilliant because she performs Isabella Bird’s tangented comments about horse breeds as sincerely valued by her or as sympathetic attempts to manoeuvre the conversation away from difficult topics.

This double-sidedness, this blending of humour and sincerity, is even more exemplified in Sophie Stemmons’ performance as Pope Joan. There is a depth and variation in her narration of Joan’s time living the ‘luxurious’ life as a Pope, while disguising her gender, which was definitely not provided merely by the script, but instead reliant on the choices of delivery.

These women and their life stories are meant to be heard against one another, compared to see their differences and, more vitally, the experiences they share—which almost always seems to be those of loss and oppression. They are, however, from the past, and so have fixed identities. The main narrative, which follows this surreal opening scene, in contrast, centres around one family, who have the genuine potential to affect one another’s lives into change. This gives a different kind of energy from the full stage of the dinner party, instead it creates a volatile anticipation.

Sisters Marlene and Joyce, performed by Aria Baker and Iona Rogan, when the share the stage, are captivating. Both are authoritative, despite their completely different life-situations—Joyce a cleaner and mother, with her cardigan wrapped tightly around her, and Marlene a travelling businesswoman in high heels. It would be an understatement to say their relationship is unresolved, but it wouldn’t be an overstatement to say it’s a relationship complex enough to be capable of carrying a play twice its length.

Sarah Mulgrew plays Angie, the 15-year-old ‘misfit’ looking for a way out or up or home, and this is yet another performance balancing humour against sincerity. Considering Angie is referred to as ‘dumb’ by multiple people, she is never cornered into this term. Sarah Mulgrew, alongside Emily Rose James’ portrayal of the even younger Kit, have an honest innocence, even ignorance, without compromising their capacity to see into and assess, sometimes judge, others, with integrity.

The seamlessly efficient set changes, orchestrated by stage manager Amber De Ruyt, enable these two scenes and settings to move into one another, as well as the third strand of the play—Marlene’s workplace. The direct interview strategy of Nell and Win—Orli Vogt-Vincent and Claire Lee Shenfield—creates a cold work environment that contrasts the intimacy of a home. But this is appropriate. And as the scenes develop, the office can seem as close-knit as Joyce’s home is cold.

Every element of this production brilliantly work with and rely upon each other. For evidence of that, you merely need to imagine a conga of historically dressed figures across a stage without Anna-Maria Woodrow’s and Maria Cleasby’s lighting and sound design to accompany them. And trust me that image is ridiculous not revelrous.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026