Rosy Sida dazzles in Oedipus at Colonus

Director Daniel Goldman provides visually stunning production with a compelling central performance, but sometimes to the neglect of the supporting roles

The story of Oedipus is one ripe with theatrical exaggeration. Having murdered his father and slept with his mother, resulting in the latter committing suicide, Oedipus blinds himself and is then exiled from his home where he was once king. The audience join him in Colonus: sick, broken, lying pale in a hospital bed and preparing to meet the end of his life. It is a testament to both the power of Greek tragedy and the artistic capabilities of director Daniel Goldman and his company that I left the theatre with my breath hitched and my hands visibly shaking. Make no mistake, the plot may appear thin compared to the drama of its prequel but what the story lacks in revelation, the cast more than make up for in raw, unfettered emotion.

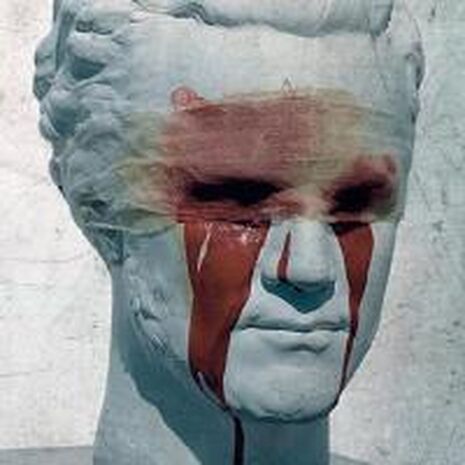

Confined to a hospital bed with her eyes hidden behind ghoulish prosthetics, Rosy Sida is the driving force of the cast as the damaged Oedipus. His story is now so well known – and so far-fetched – that it is easy to dismiss its psychological impact. Goldman, however, has addressed it head on. Sida’s Oedipus feels the tragedies of his story; he is a man overcome with regret, anger and grief. Destroyed by the recalcitrant powers of fate and reviled by those who once revered him, he has one shred of control left: the location of his death.

Sida’s monologues, delivered in ancient Greek, are intensely emotional; the perpetual tension of Oedipus’ life visible in her entire body. The quality of both her portrayal and Goldman’s direction is such that not a single moment goes by where the audience is not acutely experiencing Oedipus’ pain.

Frustratingly, though, this was sometimes was to the detriment of developing the supporting characters. Theseus (Harry Burke) and Creon (Eleanor Booton), the politicians, fell somewhere between Trump parody and genuine emotion without ever really fulfilling either. They both had some undeniably powerful moments – Booton in particular had me practically holding my breath in fear – but a sense of cohesive character was lacking.

Oedipus’ children were stronger, with particularly notable performances from Sara Hazemi as Antigone, a daughter torn between equal love for her estranged father and brother, and Harry Camp as Polyneices who amply provided the gut-wrenching misery of a son cursed to death by his father. However, compared to the depth of character displayed in Oedipus, all of the supporting characters fell somewhat short.

“The hushed soundscapes and passionate interludes of the Chorus added an edge to the agony radiating from the central action.”

The Chorus always provide a unique challenge to an updated version of a Greek tragedy. In this incarnation, they are omnipresent, circling the hospital bed. They torture Oedipus as demons in his nightmares, protect him as citizens of Colonus and even, it would seem, have control over his ever-slowing heartbeat. There are some truly spine-tingling moments with much of the sound for the play produced exclusively by the Chorus. Their hushed soundscapes and passionate interludes added an edge to the agony radiating from the central action. Nonetheless, they did seem to lack a certain element of unity, maybe because they were incarnated as members of miscellaneous hospital staff or perhaps simply due to the fact that if it’s hard to speak and act in unison in English, it’s guaranteed to be harder in ancient Greek.

The Chorus were also, as with much of the play, quite static to the extent that they occasionally started to resemble more of an onstage choir. Potentially this was intended to relieve the burden on the audience in terms of keeping an eye on the surtitles, but realistically this was an unnecessary concern. Particularly during choral interludes, the impact comes much less from what is actually being said than from how it is being said.

Immobility notwithstanding, the fluidity of the Greek language from every member of the cast (a monumental achievement led by Anthony Bowen and James Diggle) was immensely impressive. To an untrained ear, they sounded absolutely fluent, even occasionally taking the time to correct themselves when they misspoke and never sacrificing any of the poignant emotion in their words. There can be no doubt that the tradition of the Cambridge Greek Play being performed in the original language has a unique impression in comparison to a performance in translation.

A special mention must also go to the prowess of the production team. Jemima Robinson’s set is absolutely beautiful, the cyclical nature of life and death as well as the inability to escape one’s fate are reflected in the sloped circular platform denoting Oedipus’ hospital room and the Chorus’ circle of microphones. The immense circle of light hanging overhead is reminiscent of strip lights and gives the whole atmosphere a clinical, pared back feel, focussing purely on the characters. The lighting and sound from Richard Williamson and Xavier Velastin respectively also provide a perfect backdrop, contrasting the mundanity of the hospital with the gravity of inevitable death via clever use of LEDs and rumbling thunder which build and fade beautifully.

Oedipus at Colonus is a fantastic example of a Greek tragedy brought back to life in a modern reworking while retaining the rhythm and flow of the original language mastered by every member of the ensemble. It is, at its core, a psychological evaluation of a man who has lived a beyond traumatic life now attempting to come to terms with his death and it is the depth of this exploration that gives the play its power.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026

News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026