Romeo and Juliet, with Pride

‘Thy beauty hath made me effeminate’: Director Ellica Aitken discusses the challenges of adapting Romeo and Juliet into a queer love story

During rehearsals, as our lead Romeo actor laments her lost love, there comes a moment of pause as she admits to Benvolio: ‘In sadness, cousin, I do love a woman.’ When first considering the concept for our May Week garden show, I knew I wanted to adapt one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays to present a queer narrative with changed genders. However, when I proposed this to people, there seemed to be more than a few looks of confusion and hesitancy.

This comes as little surprise – the play is widely recognised as an examination of male aggression, as well as a paradigm of heterosexuality. Whether it be through watching the Baz Luhrmann adaptation and falling in love with its aesthetic, or being forced to read the Queen Mab speech aloud when studying for GCSEs, many are familiar with the text as a household name, and the themes it covers.

"Making a couple who are the paradigm of heterosexuality truly star-crossed is for us a means of reflecting what happens when you challenge society’s binaries"

Despite this, since early performances, Shakespeare has always played around with gender and its conventions. From early boy-players in Elizabethan England, the story might not have always been the heterosexual epitome that is commonplace as a stereotype currently. This has provoked figures like Oscar Wilde to consider gender in relation to the show, suggesting in The Portrait of Mr. W.H that female romantic roles like Juliet might have been constructed thinking about the young actor whom Shakespeare was in love with.

When adapting the show, I was struck just how well the play works when reimagining the play as a depiction of a lesbian relationship. A further dimension is given to lines such as the one in which Mercutio condemns Romeo for being made feminine by his love. Rather than the masquerade showing a spiritual first meeting of two souls, foreshadowing the woes of rash, young love, the play seems almost to represent a night at Glitterbomb where two strangers leave early after locking eyes as ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’ plays.

This isn’t to overshadow the sweetness of the couple’s love, but rather to help breathe new life into it. The immediate connection of finding someone just like you, as if the lovers’ meeting is a Ring of Keys moment, gains further pathos when considering the isolation of these characters in a heterosexual world. When Paris boasts that ‘Younger than she are happy mothers made,’ the sinister edge of discomfort is amplified by considering this non-consensual arrangement as a case of being forced into heterosexuality.

The Early Modern reasons for the desperation of their love can seem inaccessible to many, with lots of people having to justify their like for a play about teenagers in love by remarking on the number of ‘dick jokes’ Shakespeare throws in. But, when their relationship is believable, with tangible fear and consequences, the play transforms into one that we can better understand as being ‘never a story of more woe’. When Juliet begs for death over a forced marriage, this becomes a defence of her identity, as well as instance of clinging to the first person she has loved and understood.

Through a queer lens there is also another layer to Friar Laurence. While he is often played as a stoner-type imitation of the Priest from Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were Rabbit, it can draw more sadness to view him as being in conflict with his religion, exploring how this interferes with his acceptance of the union. As his famous warning of ‘these violent delights’ rings out, there is a foreboding warning that anyone in a queer relationship will have considered: simply for being with the one they love, unfortunately, many are familiar with the susceptibility they have to these homophobic ‘violent ends’.

When I asked our Romeo actor what she felt would be the biggest difficulty in adapting such a famous text in a gay framework, she noted the potential hardship of reclaiming a tragic narrative: “making something that is a tragedy queer, but not tragically queer.” Unfortunately, the death of prominent queer characters is a prevalent occurrence in LGBT media: the ‘bury your gays’ trope. However, I think her quote best reflects what we are trying to accomplish with this adaptation. Making a couple who are the paradigm of heterosexuality truly star-crossed is for us a means of reflecting what happens when you challenge society’s binaries of straight or queer, man or woman, Montague or Capulet.

Through this, I hope to be able to give new life to such an incredible text, as well as show modern audiences that there’s more enjoyment to be had than simply reducing an incredible love story to sexual jokes (although they are fun too).

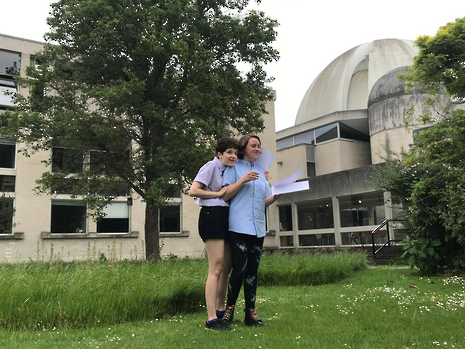

Romeo and Juliet is playing in Orchard Court, Murray Edwards on the 18th and 19th June at 2.30pm.

Features / Beyond reality checkpoint: local businesses risking being forced out by Cambridge’s tourism industry15 October 2025

Features / Beyond reality checkpoint: local businesses risking being forced out by Cambridge’s tourism industry15 October 2025 Comment / Bonnie Blue is the enemy, not the face, of female liberation13 October 2025

Comment / Bonnie Blue is the enemy, not the face, of female liberation13 October 2025 News / Cambridge climbs to third in world Uni rankings11 October 2025

News / Cambridge climbs to third in world Uni rankings11 October 2025 News / Join Varsity this Michaelmas13 October 2025

News / Join Varsity this Michaelmas13 October 2025 Features / How to spend a Cambridge summer12 October 2025

Features / How to spend a Cambridge summer12 October 2025