The Tendency to Two: a study of small-cast theatre

Why having fewer characters evokes humanity not specificity

‘Belleville’, ‘The House They Grew Up In’, ‘Anna’, ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf’, ‘Butley’. All of these plays, performed in Cambridge in the last two terms, have casts of two or three or four actors. Maybe there’s a reasonable explanation for this increased trend towards small-cast plays, a practical explanation: fewer actors makes it easier to organise rehearsals; plays with fewer actors are easier to stage in the smaller spaces that Cambridge offers.

But two-handers are also incredibly difficult to get right. The success of the whole show relies on two people having chemistry which the audience believes in, a connection which seems real and not contrived for the sake of this single performance. Call-backs in pairs are crucial: can these actors portray a story together, not just on their own? If one actor is having a bad day there is nothing to hide them – with two actors all problems are big, big problems.

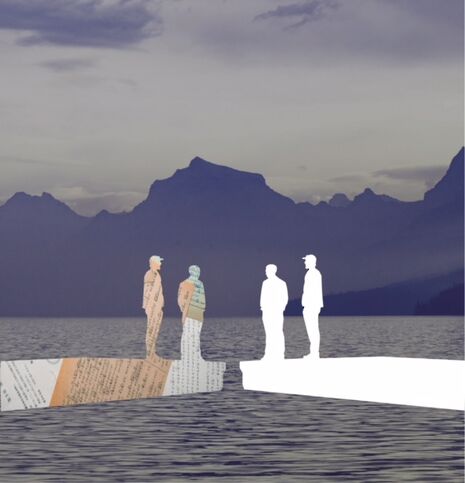

It makes little sense, then, to look at the practical motivations. What interests me is the artistic effect of having fewer characters. At its most fundamental, a play with only two characters is perhaps a character sketch. We, the audience, watch two people over a short period of time, in a specific place, interacting with each other and no one else. We become caught up in the intricacies of their personalities. What we watch is intensely specific and beautifully focused: the story of the life of another.

Yet as I write the word ‘specific’, I catch myself. There seems something so closed-off about this analysis of small-cast theatre, as if what we see stretches no further than the wings of the stage and will cease to interest once the house lights come up and we leave the theatre. I am reminded of something that a director said to me at a preview last term that has stuck with me: that yes, this is a study of two particular individuals, but it is also a study of humanity.

"What seemed to be almost a test in empathy has become something much more enlightening, revelatory even"

This might seem counter-intuitive. But look at it this way: what can be more poignant than watching someone for two hours at their most detailed, their most raw, and then realising that you are just like them? You are not this named character, you might not even live a life remotely similar to theirs, but you feel exactly what they feel as they speak and breathe and move around the stage. What seemed to be almost a test in empathy has become something much more enlightening, revelatory even, teaching you as much about your own reactions as it does about those of the characters you are watching.

Of course the effect comes in varying strengths: we feel for ‘Belleville’s Abby much more than we feel for Beckett’s Estragon, and for Estragon much more than Ben in Pinter’s ‘The Dumb Waiter’. But maybe it’s even more powerful, when we recognise even a scrap of our own thoughts or feelings in a character who does not resemble us at all. It is a moment of beauty where the small number of actors does not, I would argue, individualise, but rather generalises. At that moment they become not specific characters created for the purpose of this plot and these scenes, but representatives of a greater set – even, you could say, of humanity.

A failed two-hander can be one of the most distressing failures in theatre. A director’s worst nightmare is casting two actors who just don’t quite gel. But when it works, small-cast theatre can be some of the most human you will ever see on stage. Yet the private energy between the actors is not all: the audience needs to feel themselves in the connection. We need to watch the characters, be they like us or completely and utterly different, and nevertheless see ourselves reflected. It’s not as simple as empathy; it’s about having a vision of humanity through a different-sized lens, one that lets our feelings and thoughts seem manageable and possible, and not terrifyingly and contradictorily complex. What we have in small-cast theatre, then, is not, I would argue, a focusing in on two or three or four specific individuals but rather a zooming out to a greater question: what, in a world with such variety, brings us together as people?

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026