Neural Notworks preview: ‘computer-generated Shakespeare?’

The ADC’s first ever computer-generated performance is coming to its stage

Most academic study, no matter what subject one pursues, has the ultimate goal of finding order in the apparently chaotic existence we call home. We search for explanations for human behaviour throughout history, classify animals and diseases, draw links between authors and poets and playwrights. We formalise logic and characterise sculpture, model populations and hunt for theorems. We search for patterns in our economy, our society, and our language. It seems that to ‘explain’ something is to provide evidence or models for how or why something repeats itself. Many types of cognitive bias in fact arise because we tend to see order where there isn’t any, suggesting that this tendency to seek out patterns is somehow hard-wired into what we think of as human intelligence. Given this understanding of human intelligence, it shouldn’t be surprising that computers appear to possess something like machine intelligence when we use them to reproduce the many everyday patterns we ourselves use.

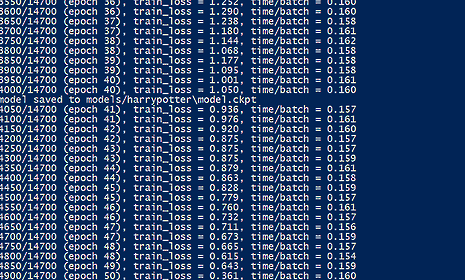

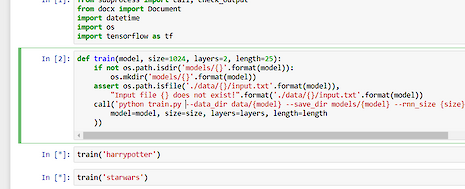

In 2015, one Andrej Karpathy kicked off a wave of popular interest in this kind of machine intelligence with the publication of a (now-famous) blog post entitled The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks. What he demonstrated was extraordinary: using nothing more than a simple model for human language and the complete works of Shakespeare, a computer could learn the Bard’s style so effectively that it might easily dupe someone unfamiliar with his works (which does tend to include many computer scientists). It turns out that, letter-by-letter, Shakespeare’s English has a consistent pattern. Without any attempt to enforce subtleties such as iambic pentameter, or even an English vocabulary, a model based on merely which letter might go after the other is powerful enough to learn both of these.

But let’s back up. What is a neural network? Popular science often claims that these are computer programs somehow designed to mimic the human brain. The reality is, while often inspired by the dense network of grey matter rattling around our skulls, neural networks are built from neurons that don’t resemble anything like ours, in structures and on a scale very different from that of our brain. Often, they can simply be thought of as a (very large) mathematical function, along the lines of ax+by=z where we know some data, x and y, some result, z, and we want to know how the two are related, a and b. The key to neural networks is that they can learn a and b, if given enough examples, as well as solving much, much more complicated problems than this, so that they can learn relationships between data that are so complex that they appear to border on the intelligent.

How does this relate to Shakespeare? Imagine any sentence as a series of letters. Some letters are more likely to come after others. For example, unless you’re playing Scrabble, ‘u’ is much more likely than ‘i’ to follow a ‘q’. The chance that the phrase “To be, or not to b” isn’t followed by ‘e’ is miniscule. Given enough examples of what letters are supposed to follow others, therefore, a neural network learns how words are spelled, how sentences are built, and even how to structure dialogue in a play. What it lacks, however, is any sense of what it is saying, leading to hilarious turns of phrase, non-sequiturs, and absurd moments.

This week, we’re bringing to the ADC stage what we believe to be its first ever computer-generated performance. The improvisational skills of the actors will be put to the test as they grapple with scripts printed live on stage in a variety of styles, ranging from Shakespeare to Fifty Shades of Grey. In a strange way, we expect to show both how ingenious and how incredibly stupid machines can be. It may be awful. It may be terrifying. It may be informative. It will certainly be unique.

Let’s end, then, with some computer generated Shakespeare:

O most pernicious muse, answer, walk

In no state truth for myself! I will welcome

This eye more black. List to them; and though

They’ll tow thee to my bed and weep to do,

Which do maintain the cause of this thrice-famed man.

I speak of thee a’who hath of strength impregnable should,

Though not like very treble did contend.

Neural Notwerks is on at the ADC Theatre at 11pm on Friday 19th January

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025