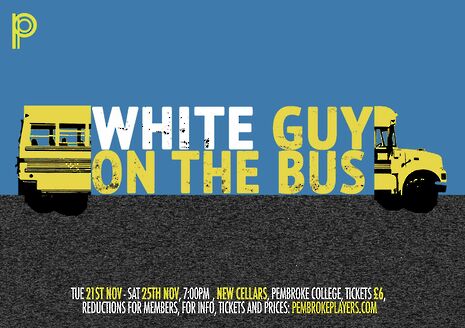

Review: White Guy on the Bus

Eve French writes that White Guy on the Bus “‘akes us for an uncomfortable ride’

White Guy on the Bus takes us for an uncomfortable ride. Bruce Graham’s script searchingly exposes the dark, dingy corners of latent racism in Philadelphia. In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus, and Freedom Riders journeyed across the segregated South in 1961. A symbol of protest, Graham’s bus is now a backdrop to enduring oppression. The writing is clever and each character finely crafted, to which Katie Woods (director) has done justice in her striking production of the play.

Ray (Benedict Clarke) is a white, successful businessman. Shatique (Arianna Hunt) is a young, black student, struggling financially while juggling parenting with visits to her brother in prison. Bouncing between their respective homes, we hop on and off the bus where their ostensible friendship develops. The shape of the staging mirrored this journey well, with the bus centre-stage acting as the spatial link between two vastly different homes and lives: a visual representation of the racial divide between Ray and Shatique. But as Ray visually crosses from his side of the stage to hers, the tone becomes increasingly sinister. Cast-aside comments and the body language of power evolve into vicious neo-slavery. Ray imposes himself upon Shatique’s world and, in doing so, symbolically conquers all territory on stage.

“Dialogue flowed with command”

The cushy warmth of suburban life shone through the props and costumes: the two white, middle-class couples constantly sipped on wine and lazed on big armchairs, spotlessly dressed to impress. Attention to detail even stretched as far as a gleaming engagement ring for Molly (Annabel Bolton). Space was maximised well, and the cast mostly responded sensitively to their settings, however there was greater potential for movement and spatial reaction in the bus scenes. Little in the performance signified that Ray and Shatique were travelling on public transport, relying too heavily on sound and set to tell this story. Pace also dipped a little in these linking scenes, although at other times dialogue flowed with command.

The cast of five was highly impressive. Clarke swept across the stage as Ray, beefed up with assurance and assumptions. His relationship with wife Roz (Jasmin Rees) was highly compelling, with both actors intertwined as a tight, pre-meditating unit. Rees glowed with the self-pride of her prize-winning character, driving friction against the more reserved Molly. The ultimate degradation and violation of Shatique was captured in Hunt’s poignant stillness, while Connor Rowlett delivered a charged and haunting dream monologue.

Pembroke Players have put on something cutting and powerful, doing justice to this play – a complex exhibition of racism. “It’s never gonna stop, Molly” may sound bleak, but the wheels on the bus are indeed still turning. This play jolts us into seeing the long road ahead on the road to racial equality

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025