Sports Law in Focus: Bosman Transfers

Keir Baker makes sense of a transfer-window favourite: the Bosman Free Transfer

The idea of a Bosman Free Transfer (‘Bosman FT’) is familiar to all those who enjoy a cheeky game of Football Manager. As one of the world’s most popular computer games, millions of its fans know that there is no greater joy than using Bosman FTs to snap up promising signings without troubling oft-limited transfer budgets. In the real world too, the size and quality of many squads have been buttressed by managers using the Bosman FT rules to bring to their clubs talented players from across the European football market.

Yet while Bosman FTs are commonly used, it is highly unlikely that many players, managers and fans have ever considered the fascinating issues of legal theory that such a transfer represents. After all, it is easy to forget that football is ultimately just a career; it still requires contracts to be signed and wages to be paid.

And just like any profession, there are times where the employee – the player – will no longer be happy working for his employer – the club. So when disputes arise between football players and football clubs, it is employment law that is used to resolve them.

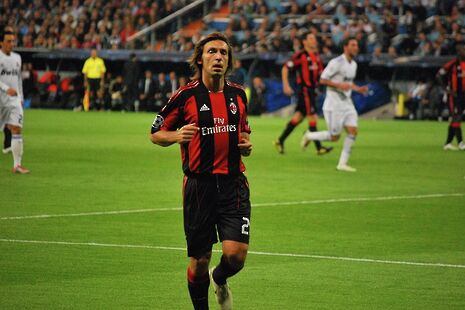

“Notable Bosman FTs have included Edgar Davids, Steve McManaman, Andrea Pirlo, Michael Ballack and Robert Lewandowski.”

In this context, the relevant piece of employment law comes from the European Court of Justice’s (ECJ) decision in Union Royale Belge des Sociétés de Football Association ASBL v Jean-Marc Bosman (1995). Here, Belgian footballer Jean-Marc Bosman’s contract with Belgian team RFC Liège had expired and, because it was not to be renewed, he wanted to transfer over to French team Dunkerque. However, a free transfer had to be granted or another club’s fee accepted, and the two teams could not agree over a transfer fee. Bosman was forced to remain playing for RFC Liège, where his wages were cut and his place in the starting eleven was lost. Outraged, Bosman took his case to the ECJ, arguing that his inability to move clubs breached one of the fundamental rules of the European Union: freedom of movement of workers.

The ECJ agreed: it held that the system – which had been put in place by European football governing body UEFA – was prohibited under European Union law, as it placed unlawful restrictions on the free movement of workers within Member States. It cited previous decisions of the ECJ to support its ruling, where it had previously been stated that nationals of Member States have the legal right to live and pursue an economic activity anywhere in the European Union, and that any rules or system which preclude or deter nationals of Member States from exercising that legal right without valid justification were unlawful.

This ruling, which created Bosman FTs, was a landmark decision. It banned restrictions by national leagues on the amount of foreign players from European Union countries that clubs could have. This led to the rules of many European-wide competitions changing: UEFA were forced to remove or modify the quotas on foreign players it had placed on the Champions League and UEFA Cup.

It also permitted players in the European Union to transfer from one club to another without a transfer fee being paid. The pendulum of power was swung significantly from clubs to players, who could demand increased wages and signing-on fees when moving on a free transfer. Notable Bosman FTs have included Edgar Davids, Steve McManaman, Andrea Pirlo, Michael Ballack and Robert Lewandowski.

For the big clubs of Europe then with the financial clout to cope with these new demands, the Bosman FT has been largely beneficial: the decision allowed for removal of legal red-tape that made it far easier to bring in the best footballing talent from across the Continent. But often overlooked is the effect that the Bosman ruling has had on the lower leagues of football; in many ways, the creation of Bosman FT has been – alongside the increasing influx of vast sums of money – one of the major factors that have undermined the competitiveness of European football.

Take the English game. Smaller clubs with well-resourced academies can no longer benefit from selling players that they developed and nurtured if they leave at the end of their contracts. The wealthiest clubs, typically competing and prospering in the cash-soaked Premier League, can afford to bring in talented players from smaller clubs by enticing players away from their clubs by offering them obscene sums of money.

And as the transfer market is flooded with money, talent becomes too expensive for smaller clubs; a deep fissure between the wealthiest clubs in the Premier League and the rest of English football has been opened up. A cut-throat environment has been created too; when a wealthy club, for whatever reason, falls into financial difficulty, it will also fall into that fissure as it is forced to sell its star players for vastly reduced prices.

It follows that there is a fascinating and fundamental question of legal theory here. When, and to what extent, should the law prioritise the needs of the community as a whole over the rights of the individual.

Indeed, it cannot be denied that the Bosman ruling was a triumph for liberty, freedom of movement, and the personal choice and autonomy of footballers. It represented everything for which the ECJ was created – giving and upholding the rights of the individual.

But for the essence of beautiful game, which is under continued attack from the forces of financial inequality, questions can be raised as to what extent Bosman FTs have contributed to the greater good

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026