Tea breaks and tedium? A (forward) defence of Test cricket

Tom Higgins Toon argues that the cricketing world must do more to ensure it preserves its most traditional format

30th August 2016. England’s batsmen thrash out a record 444 runs in 50 overs, swishing the blade left, right and centre to keep the boundaries flowing as readily as the warm pints held aloft by Trent Bridge’s enraptured spectators.

As poor as Pakistan were in the field, England were truly exceptional: with 171 runs to his name, Alex Hales now has the highest individual ODI score by an English batsman, blowing the dust off a record that had stood since 1993. Jos Buttler entered the record books too by virtue of his 22-ball half-century, while Pakistan's Mohammed Amir capped off the carnage with a quick-fire 58 – the highest ever ODI score for a number 11.

However, one could not escape the thought that this cornucopia of thrills did not really represent all that cricket has to offer. England selector Angus Fraser has since voiced his concern for the shorter format, remarking how similar exhibitions of aggressive slogging would become "a bit boring". Anyone who has watched Alastair Cook defend six good balls in a row will appreciate that the sport is not just about cheap thrills: bereft of less ‘exciting’ moments, cricket lacks a large part of its raison d’être – patience, gamesmanship and a sound judgement of when or when not to hit the ball to the fence, to name but a few.

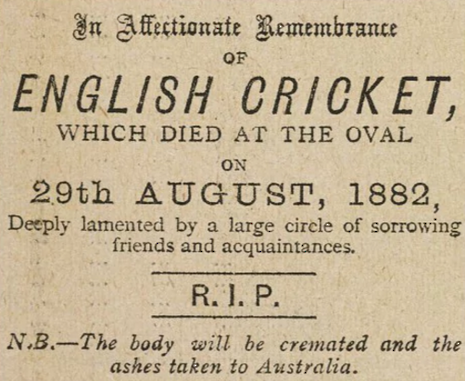

With kaleidoscopic outfits, batting powerplays and a white ball, it is no surprise that this shorter format distresses the traditionalists. Yet it is not just the incorporation of luncheon into the day’s proceedings that makes Test cricket such a remarkable spectacle; indeed, former Australian keeper Adam Gilchrist maintains that "Test cricket is the ultimate test of a player’s and a team’s ability".

In essence, five-day matches are as much about guile and psychological strength as raw talent, which serves to explain to a certain extent why many players are more suited to one format or the other. In one of the Tests this summer, it was Hales himself who, frustrated following several maidens from Yasir Shah, attempted to heave the leg-spinner out of the ground, only to mistime his ugly swipe straight to the fielder. This was a meticulously-planned manoeuvre to channel the England opener’s natural aggression into a weakness, the fruit of cunning captaincy and patient perseverance.

Test cricket is, after all, an intellectual affair, where bowlers pit their wits against batsmen in a fair contest between the proverbial leather and willow. Alongside this mental dimension, Tests bring out all the complexities of the game discarded by limited-overs cricket. Without nightwatchmen, reverse swing and unpredictable rough patches outside off-stump making an absolute fool of first-rate batsmen – think Shane Warne to Andrew Strauss in 2005 – it seems much of the game’s compelling qualities have been lost in translation.

Of course, the logistics of the Test format can lead to disappointment and anti-climax. Many games are decided well before the fifth day, and inclement weather conditions may snatch away victory from a team. However, such is the magic potential of the Test format that, when all determining factors conspire to generate a thrilling conclusion, the result often leaves an enduring mark on cricketing history. Any passionate England supporter worth their salt will remember the nervy suspense and growing sense of excitement as Jimmy Anderson and Monty Panesar – who averages fewer than five runs in Tests – somehow survived a 40-minute Australian onslaught to save the opening Ashes Test in Cardiff back in 2009.

In any case, limited-overs cricket has caused the longer format to evolve – for better or for worse. Of the 185 Test matches between 2010 and 2015 that produced a result, fewer than a third reached the final day, with more aggressive batting frequently cited as an explanation. This would not be so problematic if higher run rates continued to generate close results, but this does not seem to be the case. Over the last 10 years, only once has a team won a Test match by the narrowest margin of just one wicket (India vs. Australia, 2010), compared with five occasions in the preceding 10 years. While the 2005 Ashes Test at Edgbaston will not be quickly forgotten – thanks to England snatching victory with two runs to spare – it was only the second time since 1993 that a Test had been decided by fewer than 10 runs.

Despite the grandeur of these historic moments and quirky complexities that make up the rich fabric of Test cricket, its future remains uncertain so long as money is concentrated in the more lucrative forms of the game. Certain high-profile players – Kevin Pietersen and Chris Gayle instantly spring to mind – have essentially turned into freelancers, participating in local T20 franchises all over the world. In so doing, they can tap into financial resources that are simply not available to England’s top county players, who receive a maximum annual salary of £400,000 paid out by the England and Wales Cricket Board. To put this into context, the top five richest cricketers all start on salaries exceeding US$3 million, a figure which rises around tenfold once sponsorship deals are added into the equation.

With plans mooted for fluorescent pink balls, day/night tests and a three-day Test championship, it would seem that the International Cricket Council (ICC) is trying to redress the balance by creating a modernised conception of Test cricket. However, the risk is that such modifications simply serve to remove the key idiosyncrasies that distinguish Tests from their more lucrative offshoots.

Even sexed-up Test cricket cannot compete with the limited-overs format in terms of providing cheap thrills for short attention spans, and the broadcasters know it. Instead, we should embrace all the values promoted by the longer format – with Test cricket, the clue is in the name.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025