Epilepsy: a short history

Epilepsy today is a medical conundrum and a human tragedy, argues Michael Baumgartner

Before I get into the meat of this article, I have a conflict of interest to disclose: I study epilepsy as a doctoral candidate here at the university, and as inevitably happens with researchers, I have come to believe that everyone ought to dedicate more attention, care and money to this (my) topic. This piece, therefore, is a shameless attempt to sway you and everyone else who reads it over to my way of thinking. The story of epilepsy straddles the realms of public health, anthropology, spirituality, biology and philosophy. As a result, it is both a medical crisis and a window onto how people work, both on a functional and cultural level. Here, I aim to provide a snapshot of a misunderstood and neglected condition that, I hope, will inspire some of you to take a moment to learn about the ‘Sacred Disease.’

Unique among most medical concerns, epilepsy has a long written history. The distinctive symptoms of a seizure which make it a staple of medical dramas also make it relatively easy to identify in ancient texts. Over millennia and across civilisations, people with epilepsy have suffered harsh discrimination. Legal references to epilepsy (or at least some forms of epilepsy and visually similar disorders) go back as far as the Code of Hammurabi, which decreed that those suffering from ‘the Falling Sickness’ could not marry or testify in court. Versions of these enlightened laws persisted in the US and UK legal codes until 1980 and 1970, respectively. Athenian Law dictated that, should your slave suffer a seizure, you were entitled to a refund, unless of course you were a physician and should have known better. Modern history has not been kind, either, where epileptics were caught up in the tragedies of the Holocaust and eugenics programmes.

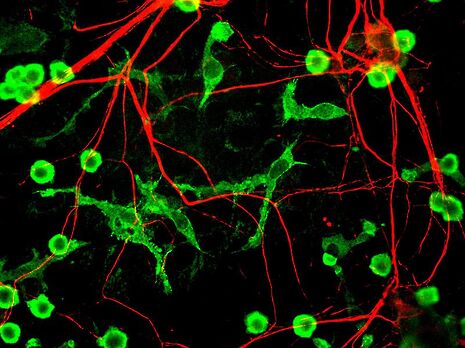

Perhaps these visceral reactions to seizures result from the condition’s unique physical symptoms: an otherwise healthy-looking individual abruptly comes down with convulsions, as if being seized by some outside will. This loss of control of one’s own body is not a supernatural phenomenon. It derives from the functional changes in the brain that drive epilepsy. Even today, epilepsy is not well understood. It is generally accepted, however, that epilepsy is the result of aberrant brain-cell-to-brain-cell communication. This is a mechanism believed to underpin how the mind – and therefore human behavior – functions. This adds to the challenge of epilepsy research. Neuroscientist Cristophe Bernard summarises the challenge: “Since we do not have a comprehensive understanding of how the brain works, it is very difficult to generate a sound hypothesis-driven research strategy to uncover the mechanisms of epileptogenesis”. Given that epilepsy is a result of atypical brain signaling, any movement, emotion, noise, sensation or perception can therefore occur during a seizure. Most people are surprised to learn that seizures can come in virtually any form, from staring spells to dreamy, hallucinatory states.

In spite of these complications, the scientific community has largely reached a consensus on what is necessary for a seizure to occur: hyperexcitability and hypersynchrony. To understand these terms, one can think of neurons – what scientists generally refer to when they say ‘brain cells’ – as biological switches. This is a simplification, but an illustrative one. Normally, neurons are tightly regulated: they only switch on or fire in specific circumstances. For instance, neurons associated with perceiving the color purple only send a signal when purple light hits the retina. During a seizure, neurons are more likely to switch on, even without the stimulus. We therefore say that they are hyper-excitable. These neurons also tend to recruit other neurons to fire, causing a spread of unregulated signaling in the brain, which is termed hyper-synchrony. A consensus on where these symptoms come from and how they manifest, however, has eluded modern science.

Medical advances in epilepsy treatments and seizure management, therefore, seem to occur in fits and starts, sometimes as serendipitous byproducts of misguided hypotheses. The first legitimate breakthrough in epilepsy treatment seems like a scene from a black comedy. Victorian doctors, being Victorians, believed the cause of epilepsy was sexual deviancy. Some historians, therefore, attribute the discovery of the first effective anticonvulsant, potassium bromide, to its ability to cause impotence.

Stories aside, epilepsy today is a medical conundrum and a human tragedy. This brings us to the morbid statistics that inevitably accompany discussions of medical conditions competing for research dollars. Epilepsy is an extremely common condition, afflicting an estimated fifty million people worldwide. And while the vast majority of cases occur in the developing world (80 per cent), epilepsy treatments are generally not easy to administer in places without medical infrastructure. As a result, the vast majority of people with epilepsy in the developing world, roughly three quarters, do not receive treatment. Of all patients who do receive treatment, medicines fail to control seizures roughly a third of the time. For them, the best option is usually highly invasive and wildly expensive brain surgery. For those who suffer from epilepsy in some of its most vicious and debilitating forms – those who seize so regularly that they are rarely fully conscious, unlikely to ever develop or learn to speak, walk, or dress themselves – surgeons sometimes perform a hemispherectomy, in which they disconnect a full cerebral hemisphere.

Unfortunately, progress is slow going. According to Orrin Devinsky, M.D., director of the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center: “We’ve introduced a dozen new drugs in the past 20 years, but it’s not clear we’ve made a significant advance in the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy. We have failed as a scientific and medical community.”

In spite of these statistics, the outlook for epilepsy treatment is not wholly bleak. Progress has been made, sometimes by Victorian happenstance and sometimes driven by brilliant and passionate minds like Wilder Penfield and Herbert Jasper. While better treatments are needed, the ones we have can and do work wonders and need to be more available worldwide. So, if you are a wide-eyed student looking for direction, maybe take a look at epilepsy. I can think of fifty million people who could use your help.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026