Does the mpox outbreak spell disaster for global health?

Following the declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, Ruby Jackson explores just how worried we need to be about mpox

On 14 August, the World Health Organisation’s director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) - the ‘highest level of alarm’ the organisation can issue - over growing concerns about the spread of mpox.

This is the second such declaration the WHO has made in two years. An outbreak of mpox that began in June 2022 saw nearly 100,000 cases and 208 deaths before that PHEIC was declared over in May 2023. The announcement about the most recent outbreak, however, has been accompanied by warnings from experts that it has the potential to be far more serious than any we’ve seen before. So, how concerned do we need to be?

What is mpox?

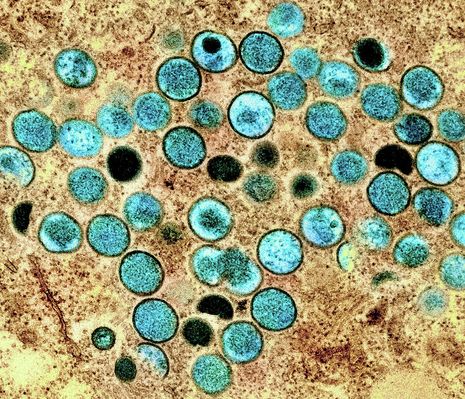

Mpox refers to the illness caused by the monkeypox virus. The disease initially presents with flu-like symptoms including fever, muscle aches and swollen glands, followed by the appearance of a rash that often looks similar to chickenpox. While the illness is usually mild and resolves within a few weeks, it has the potential to be deadly. Older people, young children and those with weakened immune systems are at highest risk of needing treatment in hospital.

There is currently no vaccine available against mpox, but smallpox vaccination offers some cross-protection, so has been used to control previous outbreaks. This is because variola (the virus which causes smallpox) is closely related to the monkeypox virus - both belong to the Orthopoxvirus genus and are thought to have evolved from a common ancestor.

“The recent outbreak is much more worrying than the one that occurred in 2022”

The illness was originally given the name monkeypox after it was first identified in a group of monkeys kept for research in Copenhagen in 1958. Monkeypox is a misnomer; it is now believed that the natural hosts of the virus are rodents and other small mammals. However, it’s capable of infecting a wide range of mammals, ranging from anteaters to hedgehogs. The first recorded case in a human patient occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 1970, and since then the disease has been endemic in areas of Central and West Africa. Outbreaks here have been increasing in frequency and severity over recent decades, probably due to a decline in immunity following the cessation of smallpox vaccination programmes.

What makes this outbreak different?

The outbreak of mpox in 2022 was the first incidence of widespread person-to-person transmission outside of Africa. It sparked a global response that included vaccination programmes and increasing public health information, which was ultimately successful in reducing transmission. However, a new strain of mpox is responsible for the more recent outbreak, which is much more worrying than the one that occurred in 2022.

“Estimates of the mortality rate for the new subvariant stand at around 5%”

Monkeypox virus is split into two major genetic groups, known as Clade I and Clade II. A variant of Clade II was responsible for the 2022 outbreak, but the most recent outbreak is being caused by a subvariant of Clade I, known as Ib, which is much more transmissible. While in 2022, the virus primarily spread through very close contact, often during sex, the more infectious nature of Clade Ib means it can be transmitted by less intimate contact, such as breathing in the virus, and via fomites (objects contaminated by viral particles, like clothes or towels). This makes it much harder to prevent transmission and control the spread of the disease.

The illness caused by Clade Ib also tends to last longer and be more deadly. Estimates of the mortality rate for the new subvariant stand at around 5% in adults and 10% in children, compared to below 1% for the variant causing the 2022 epidemic.

How do we prevent the spread?

Measures to prevent mpox becoming a global pandemic must reduce the rate of transmission. The effective reproduction number, or ‘R number’ of a disease is a term most of us will remember hearing during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. It refers to the average number of people a single person with the disease will go on to infect. An R number below one suggests an outbreak will be self-limiting, while an R number above one means there is potential for the disease to spread rapidly. The R number varies depending on both the transmissibility of the virus and how susceptible a population is, and can be reduced by interventions like vaccination and limiting close contact.

Good news – the R number for mpox is unlikely to be very much above one at the moment, so epidemiologists are optimistic it’s possible to reduce transmission and control the spread with strong public health measures. However, these rely on good health infrastructure and considerable resources, meaning it’s likely the epidemic will disproportionately affect low-income countries without this capacity to respond. The DRC is currently by far the worst affected, and it seems likely they will struggle to contain the outbreak. Conflict in the east of the country has led to widespread deaths and displacement, and UNICEF has raised concerns the disease is likely to spread rapidly in refugee camps. The national healthcare system is already under increased pressure due to outbreaks of cholera and measles and widespread malnutrition. Congolese Health Minister Samuel-Roger Kamba estimates the DRC will need nearly 3 million doses of vaccines to limit the spread, but expressed concern that this will be ‘very expensive’ and the country is likely to require foreign aid.

The declaration of a PHEIC should unlock additional funding that is only available in response to an emergency, but it seems likely low-income countries will still bear the brunt of the epidemic. With warnings about the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on global health inequality still ringing in our ears, it is crucial the response to this mpox outbreak avoids worsening this disparity.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025