Hearing without listening – the power of metaphor

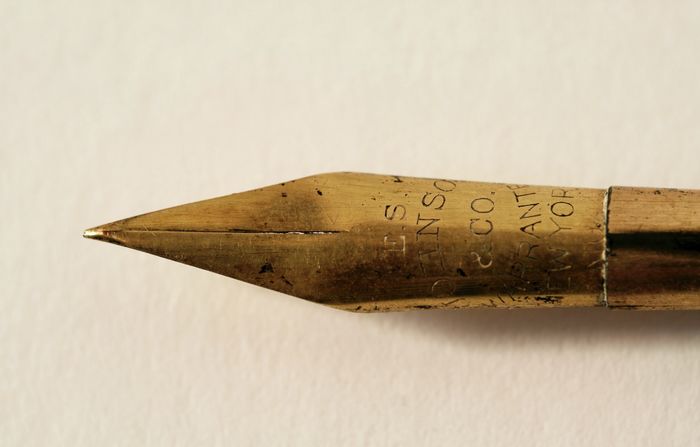

Metaphors may seem like a simple stylistic device taught by your Year 3 teachers – but they are a lot more than that

I only realised I lived next to a railway line when I moved back home from Cambridge. How did I ever sleep or think through the sound of freight trains passing by every 15 minutes? Sure enough, after a week or so, I promptly forgot that I lived next to a railway line: I’d started hearing without listening.

Metaphor is such an integral part of our speech - up to 10% by some accounts - that we are frequently unaware that we’re hearing it. We can talk of spending time like it’s money, or we can talk about prices rising as if that money is some balloon. Even words like sole (the fish) originate from a metaphor because this flat-fish supposedly resembled the sole of a shoe. Ultimately, metaphors help us conceptualise things that the brain is simply not designed to conceptualise. Death, religion, and time, for example, are rarely spoken about outside of metaphorical terms, probably reflecting the limits of our thought processes. How we frame concepts have a lot of influence over the way we reason with them.

Another new flood of concepts emerged in early 2020, putting the limits of metaphor to the test in conveying complex yet vital scientific information to the public. In the initial days of the pandemic, metaphors of war abounded. There was talk of shielding the vulnerable, securing workplaces, and defeating the invisible enemy. Given the horrific conditions in hospitals and daily death tolls, one might think this was a natural conclusion, but leaders’ overreliance on military metaphor quickly attracted criticism, led by the trend #reframeCovid.

“The human brain is fundamentally dependent on analogies and metaphors for making sense of abstract concepts”

The arguments hinge on the key problem with metaphors – people take them too seriously. If the pandemic is a war, then it is all too easy to extend the metaphor and say people who catch coronavirus somehow didn’t ‘fight’ hard enough, or that individual protective measures don’t matter as much as the collective ‘frontline’. This very line of reasoning led people to assume ‘leaving the EU’ would be the same as ‘before the EU’. If you leave a building, you will generally find yourself in the same state and position as when you entered it, but the same is untrue for countries and international organisations. Interestingly, Boris Johnson stands out for the extraordinary frequency of metaphors in his speech, with war-related metaphors accounting for around 4% of everything said in press conferences during the first weeks of the pandemic. Meanwhile, other leaders like Nicola Sturgeon tended towards more psychologically-friendly metaphors relating to journeys - noting prophetically in April 2020 ’We’re in this for the long haul.

It has long been argued that our deep frames of reference, our worldviews – shaped by cultural environment, education, and experience – might well be grounded in metaphorical conceptualisations. It’s already common currency in anthropology; the Aymara people of Brazil famously refer to the past as in front of them, and the future behind them, unseen and unknown. By the same logic, they are not walking actively through time, but instead, it passes around them like water around a boat. This view is not forced on them by their language, but the metaphor can help to reveal the way the Aymara minds carve up a messy, confusing world around them.

“Our deep frames of reference, our worldviews, might well be grounded in metaphorical conceptualisations”

This same approach can help to explain why conspiracy theories (which always seem bizarre to the average person) can seem genuine to other people. It’s well known that through a process of repetitive reinforcement, incorrect claims begin to be embedded into a person’s knowledge and views. However, conspiracy theories also tend to pick up on common mental shortcuts which we can observe through metaphor. For example, Joe Biden frequently refers to himself as ‘Irish’ rather than ‘third-generation Irish’, a linguistic indicator of a simplification which leads many Americans to equate heritage with nationality. Take this one step further, and it’s clear how racist ‘birther’ theories might take advantage of this and argue that ethnicity is equivalent to birthplace. Unfortunately, however, it is virtually impossible to alter a an adult’s frame of reference though logical argument alone. The mind is not a logical machine - it takes shortcuts, and falls back on well-established networks in preference to the unfamiliar.

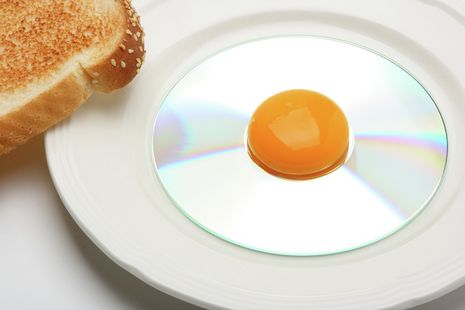

The human brain is fundamentally dependent on analogies and metaphors for making sense of abstract concepts, especially those we can neither see nor hear. One famous experiment presented participants with a text describing the city as ‘ravaged’ by crime while another group read about the same city ‘infested with crime’, both using otherwise identical statistics and arguments. At the end of the experiment, people in the first group were more likely to vote for increased police power. The wording of the text alone trumped political alignment, gender, and class as predictors of voting tendencies. And yet, not one participant identified it was the metaphor that had influenced their decision: even when showed the experimental design, they insisted that statistics alone had led them to make their decision. Metaphors pass by us like trains in the night – but unlike the trains, they have a tangible impact on the way you think.

When politicians, con men, spin doctors and liars are all quick to offer us a handy metaphor, it’s rare that we stop and ask why. Is it because they want to simplify a complex topic into a sound bite? Or are they trying to reframe the way you think about a particular issue? So, be vigilant: metaphors can lend a helping hand, but they can also lead us astray.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025