Why your birth assigned sex may not match your genetics

Natasha Reid discusses intersex conditions, considering how they can arise and why intersex individuals are often let down by society

February is well known for being LGBT+ month. Whilst everybody knows about the L, G, B, and T, with many colleges hanging pride flags from their buildings, most of the population are much less acquainted with the ‘+’. The full expansion is LGBTQQIAAP, but let’s zoom in on the 'I', which stands for intersex. The Oxford Dictionary defines intersex as “a person…having male and female reproductive organs, or in which the chromosomal patterns do not fall under typical definitions of male and female”. This is an important definition, highlighting that intersex people are not disfigured; they are just on the physiological spectrum between male and female. And of course, here we are only considering the physiological sex at birth – not how an individual perceives themselves as they age.

History has a track record of deep misunderstandings surrounding intersex people. Around the world, cultures have responded in different ways, with stigma generally being higher in western societies. Care given to neonates was poor and secretive, and intersex individuals typically carried this ‘need to hide’ into adulthood. Interestingly, there are cultures that attribute intersex people to a ‘third gender’, such as the berdache in native Northern America, the hijra in North India, or the Mahu in Tahiti, who have assumed respected roles within the community.

To counteract the historically poor care provision, new nomenclature for intersex conditions was introduced by Cambridge’s Paediatric Department in Addenbrooke’s Hospital. The new term is ‘disorders of sex development’ (DSD). This is a crucial cultural shift, not only because the new names are more accessible and easy to understand, but also because traditional terms such as ‘hermaphrodite’ were culturally loaded and perceived as derogatory.

There are lots of different conditions that fall under the umbrella of intersex. In humans, the phenotypic sex is usually determined by a pair of sex chromosomes: females being the homogametic (XX) sex and males being the heterogametic (XY) sex. Usually, genetic sex determines gonadal sex; however, this is not always the case. If anything in the sex-determining cascade is faulty, it can result in disjunction between genetic and phenotypic sex, leading to a complete spectrum of phenotypic genders.

“If anything in the sex determining cascade is faulty, it can result in disjunction between genetic and phenotypic sex, leading to a complete spectrum of phenotypic genders”

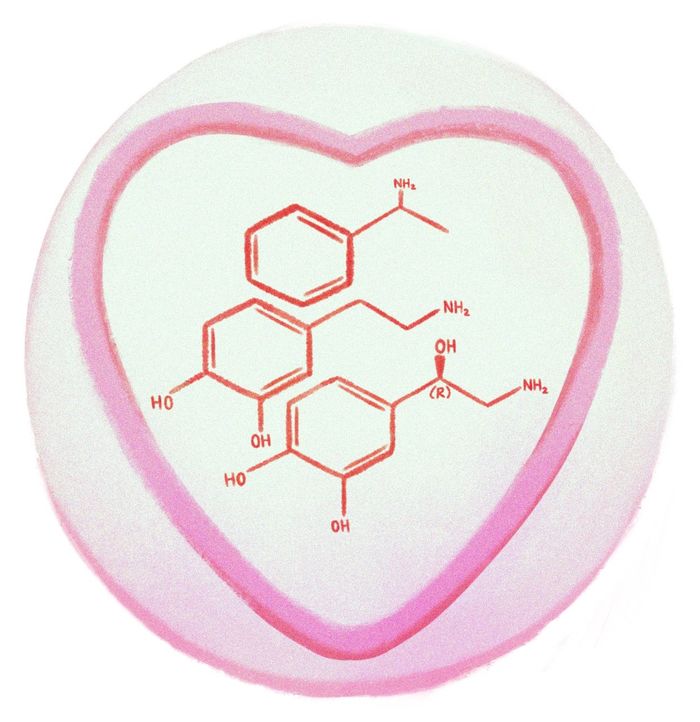

Male and female genitalia develop differently because of a hormone called 5a-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which is essentially a stronger, more powerful version of testosterone. DHT is present around the local tissue of developing genitals in males but not in females. So, if someone with XY chromosomes were to have a DHT deficiency, they would develop female genitals. This condition is known as guevedoces. However, the difficult psychosocial element for people with guevedoces is that they will have female genitals when born, but suddenly develop male genitalia as testosterone levels rise at puberty. Interestingly, most people with guevedoces exhibit socially conventional heterosexual male behaviour and sexual orientation. A famous case that gained significant public interest featured people in the town of Las Salinas in the Dominican Republic, where guevedoces was found in 1 in every 90 males.

On the other hand, even with DHT present, an XY individual could still have a female sexual appearance due to androgen insensitivity syndrome. Individuals may be simply unable to respond to the androgens in their body even though they have completely normal androgen production and normal testes!

People with XX chromosomes can also have disordered sex development. If androgen production is too high, as in congenital adrenal hyperplasia, they can have partial masculinisation of their external genitalia noticeable at birth. This can be confusing for parents, as their child’s genitalia will be ambiguous, and they may not know how to ‘announce’ their newborn's gender to their loved ones.

The most well-known form of intersex is probably true gonadal intersex, where people have one testicle and one ovary. This is rare because of strong positive feedback loops during the early stages of development; it would be more common to have gonads containing both testicular and ovarian tissue. The phenotype could be either male or female, but the external genitalia are always ambiguous.

Abnormal external genitalia can increase the likelihood of long-term mental health difficulties, as gender assignment at birth has a large impact on self-identity. Only Malta (2015) and Chile (2016) have made it illegal to perform non-consensual ‘corrective’ surgeries on children with ambiguous genitalia. Consequently, medico-legal cases can arise when patients realise that they were treated poorly by doctors and seek compensation for the mental and physical stress endured.

“With the increasing recognition of intersex rights and with the new, less stigmatised nomenclature, society can move away from regarding intersex people as diseased or disfigured, and instead as humans”

Christiane Völling was born in Germany with XX sex chromosomes. She had ambiguous genitalia and her doctor decided that she should be assigned and raised male. She was told that testicular tissue had been detected, but in reality, this was not the case – in fact, she had a complete female internal reproductive system. Despite telling her that they were removing testicular and ovarian tissue, the doctor removed all her female tissue without her consent. On top of all of this, she was even found to have the female genotype XX, but this result was hidden. In 2006, aged 47, she obtained her medical records and discovered the concealment of her chromosomal diagnosis and the lies around her surgery. As the surgeon had no good reason to withhold her diagnostic information, the International Commission of Jurists described her case as “an example of an individual who was subjected to sex reassignment surgery without full knowledge or consent.”

It is likely that this has happened more times than documented, as patients have very limited awareness of what has been done to them. However, with the increasing recognition of intersex rights and with the new, less stigmatised nomenclature, society can move away from regarding intersex people as diseased or disfigured, and instead as humans on the spectrum between physiological male and female. In essence, any one of us could have been born with external genitalia that does not match our chromosomes, but that would not change us as people.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026

News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026 News / Lucy Cav students go on rent strike over hot water issues6 February 2026

News / Lucy Cav students go on rent strike over hot water issues6 February 2026