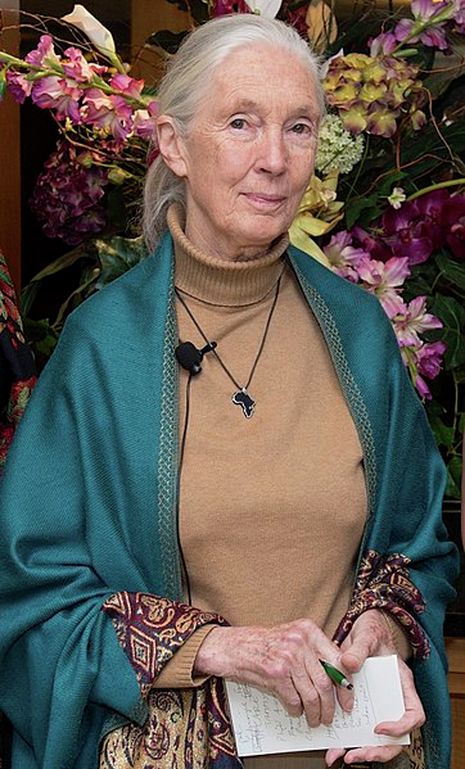

From Gombe to the Union’s Hawking Fellowship: A look at Jane Goodall’s remarkable career

Kate Howlett delves deeply into the remarkable career and contributions of Dame Jane Goodall.

When Jane Goodall made her first major discoveries about chimpanzees, she faced opposition from many both within and outside the field of anthropology. Not only was she a young woman conducting cutting-edge research with little-to-no training, but she insisted on talking about the personalities of the chimpanzees she knew. Fast forward to today: she is now recognised as having made revolutionary contributions to the science of ethology, and is acknowledged as a world-leading conservationist and animal rights activist.

Goodall left the UK for Kenya in 1957, aged just 23, to pursue her dream of studying animals in the wild. There, thanks to a blessing of good fortune, she met the famous palaeoanthropologist Dr Louis Leakey, who employed her as a secretary; he quickly realised that her fascination for animals was not just a passing phase, and so offered her a job studying wild chimpanzees at the Gombe Stream Reserve (now a National Park). Other than a two-and-a-half-month study conducted 30 years previously by Dr Henry Nissen, no one had spent an extended period of time observing wild chimpanzee behaviour. At the time, no one predicted quite how long the Gombe research project would last.

In 1960, having secured a small amount of money for essentials, Goodall headed into the forest with her mother, Vanne, bringing little more than a notebook and a pair of binoculars. It took her several months for any of the chimpanzees to allow her to come close enough to observe them, and Goodall often cites those first few months as the most difficult period of her research. Time was quickly running out for her to discover something significant enough to secure more funds and continue the project.

Eventually, four long months after arriving at Gombe and relentlessly clambering around the forests, a chimpanzee whom Jane had named David Greybeard, on account of his distinctive grey chin hairs, gifted her her first major observation: watching from a good distance away through her binoculars, Goodall observed him carefully trimming the edges of a blade of grass before inserting it into a hole in a termite nest. She had observed a chimpanzee not just using a tool but making one.

Other animals had, at this point, already been observed to use tools in the wild, but no non-human animal had been known to make them, something then held as central to anthropologists’ definition of humans. After telegramming her unprecedented discovery through to Leakey, she received the following famous reply: ‘…scientists holding to this definition are faced with three choices: they must accept chimpanzees as man, by definition; they must redefine man; or they must redefine tools.’ Goodall’s discovery sent shockwaves through the world of anthropology. Many struggled to accept her observations, with some even claiming she had taught the chimpanzees herself!

Once this was coupled with her second major discovery – that chimpanzees hunt and eat meat, when they had previously been presumed to be vegetarian – a batch of funding from the National Geographic Society was secured, and the Gombe Stream research project became firmly established.

“Having now reached 60 years of continuous data collection and monitoring, it has yielded a wealth of knowledge about the complex structure of chimpanzee society, their multifaceted relationships with one another and the true extent of their emotional and conventional intelligence.”

These discoveries sparked the beginning of the longest running study ever conducted on wild chimpanzees. Having now reached 60 years of continuous data collection and monitoring, it has yielded a wealth of knowledge about the complex structure of chimpanzee society, their multifaceted relationships with one another and the true extent of their emotional and conventional intelligence.

In 1962, Leakey enrolled Goodall in a PhD in Ethology at the University of Cambridge under the supervision of Robert Hinde; Goodall had never previously heard of the subject. Here, she battled continual opposition to the idea of calling chimpanzees by name, talking about their personalities or emotions, or even using gendered pronouns to describe their actions. On submitting her first paper for publication, the editors crossed out every ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘who’, replacing them with ‘it’ and ‘which’. Furious, Goodall crossed the objectifying pronouns out, unbothered by the possible reactions of the editors; the journal eventually relented.

Despite these early struggles, Goodall succeeded in bringing the fascinating lives of the Gombe chimpanzees into the public eye. Some achieved near-celebrity status, notably the following: the gentle David Greybeard, who first accepted Jane as a strange, hairless but harmless ape; the playful, mischievous young Fifi, who went on to mother the most offspring of any chimpanzee in the reserve to this day; and old Flo, who was even granted an obituary in The Sunday Times when she passed away in 1972.

But Goodall’s contributions go beyond just her observations of chimpanzees’ capacity for love and compassion; she also observed a four-year long period of warfare between the neighbouring chimpanzee communities of Kasakela and Kahama, which led to the deaths of at least six chimpanzees in a variety of brutal ways and to the disappearances of five more. This quickly contributed to the public opinion of chimpanzees as violent, aggressive animals. Even now, on typing ‘chimpanzee’ into Google, the first suggestion is ‘chimpanzee attack’, the sixth ‘chimpanzee strength’ and the seventh ‘chimpanzee rips face off’. Given the vastly greater number of observations which hint at the deep levels of care and compassion in our great ape relative, one wonders whether this says more about humans than it does about chimpanzees.

“... are we, at our core, aggressive animals whose violent tendencies are only kept in check by human society, or are we caring, compassionate individuals whose violent mishaps are the result of society’s pressures and restrictions?”

Until Goodall observed this behaviour, we were the only animals known to engage in warfare. Yet again, she had discovered a behaviour which pulled our two species closer together across evolutionary time. The centuries-old debate between philosophers Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau on the true nature of humankind was rekindled: are we, at our core, aggressive animals whose violent tendencies are only kept in check by human society, or are we caring, compassionate individuals whose violent mishaps are the result of society’s pressures and restrictions? As with the majority of these debates, the dichotomy is a false one, and the truth probably lies somewhere between the two. But Goodall certainly brought discussions about the evolutionary origins of ‘human’ behaviours into the public sphere.

Around the late 1980s, Goodall’s focus underwent a shift from increasing our understanding of chimpanzee behaviour to spreading awareness of their plight. Citing a 1986 conference in Chicago as the turning point, Goodall now spends up to 300 days a year travelling around the world to tell the story of wild chimpanzees and their struggle for survival in a world which leaves less and less space for them. Threatened by habitat loss due to climate change and land conversion, as well as by the bushmeat and pet trades, chimpanzee populations have declined by 90% in the last 20 years in key areas of their (now much reduced) range.

“Her philosophy is a powerful one: humans will not save wild chimpanzees if they do not care about them, and we cannot possibly care for them if we don’t understand them.”

Goodall combines her work for chimpanzee conservation with her campaigns for animal welfare and the humane treatment of chimpanzees in captivity, either for medical testing or in zoos, and for the ban of chimpanzees in cosmetics testing and as pets. Her philosophy is a powerful one: humans will not save wild chimpanzees if they do not care about them, and we cannot possibly care for them if we don’t understand them.

Goodall founded the Roots & Shoots programme in 1991, after a group of young people confided in her about their concerns for the future of the natural world. The programme now operates in 50 countries and has 700,000 members, helping young people work for and implement positive change for themselves, the environment and the animals they share it with.

Her community-focused work and sheer dogged optimism, which she frequently cites as stemming from working with hopeful young people keen to bring about change, has earned her the appointment as UN Messenger for Peace and a DBE. Her full list of awards and honours is extensive enough to merit its own article, but it includes the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s most prestigious award), the Benjamin Franklin Medal for life sciences, and the Gandhi-King Award for non-violence. But, perhaps most important of all, her legacy will be a generation of informed, compassionate environmental leaders, who have both hope for the future and the tools to affect change.

Jane Goodall has been named as speaker for the Professor Hawking Fellowship Lecture 2020 at the Cambridge Union. The Fellowship goes to those who are distinguished in STEM and have made a historic contribution to social discourse. Goodall has achieved both with flying colours, having revolutionised our understanding of primate behaviour and committed several decades to spreading awareness of animal welfare and conservation issues. The virtual lecture will take place on Monday 9th November.

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026 News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026

News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026 Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026

Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026 Music / Inside Radiohead’s circle13 January 2026

Music / Inside Radiohead’s circle13 January 2026