The limits of popular science

An unfortunate truth puts a limit on the level of understanding we can achieve through popular science

For any previous or current readers of popular science, I suggest that the following phrases will be familiar. Those books referring to the allures of string theory can’t resist discussing “the role that symmetry plays in modern physics”. Others leave the reader on a mathematical precipice, describing the relevant technicalities as “unnecessary to avoid confusion, with the details left to the more experienced”.

I’d like to clarify my position quickly. First, I have very much enjoyed reading a large number of popular science titles: they were instrumental in sparking my interest in the subject. As such, the role they can play in introducing people to new ideas and difficult concepts is not only a pleasant artefact of the genre, but a vital element of scientific education. My argument, however, is that given the almost total absence of technicality, there is a limit to their approach and the understanding they can bestow.

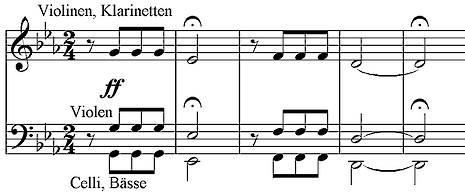

The discussion here really comes down to language. It is an unfortunate – or fortunate – truth that the language of science is mathematics and statistics. I’ll make an analogy with music to illustrate the point. Take Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony: in all likelihood, if I wanted to, I could tell you about how the melody moves and how the phrases rise and fall. I could even go to the length of describing each and every note in words. In order to fully understand, and indeed perform the piece, however, we need more. In this case, the language of music is staves, clefs, flats, and sharps. Without this abstraction, our description lacks a great deal of clarity.

I'd argue that this idea holds true for science also. The reason for this lies in the pure fact that some ideas are just strange. There are results that have no analogy in our real-world existence, such as the beahviour of objects around black holes, the electron’s true interaction with atoms, or the sheer oddity of much of quantum mechanics. These results fall out of the calculations alone, and while they perhaps appear nonsensical, in true Sherlock Holmes fashion, the logical underpinning of the subject renders them the only reasonable deduction.

“It is an unfortunate – or fortunate – truth that the language of science is mathematics and statistics.”

It is this admission that I feel popular science often neglects to mention. The fact is that sometimes, or even often, physicists, chemists, and biologists can’t provide a solid, common sense reason for something to be true, and yet it is backed up by strong experimental or mathematical proof. As such, if you have perhaps brushed the surface but felt intimidated by an idea or concept, I would urge you to embrace the very real confusions of the subject and read on

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025