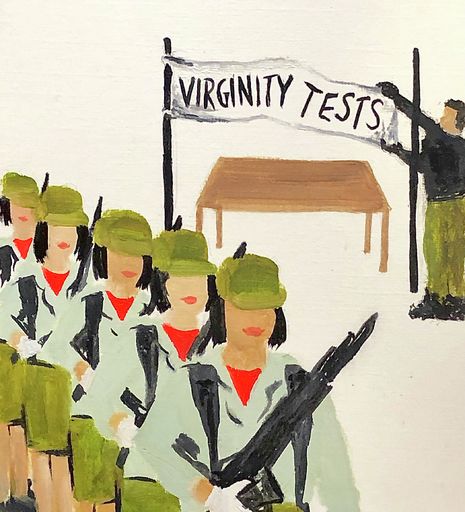

Virginity testing: is the end in sight?

So-called ‘virginity testing’ has been and still is practised globally, under a myriad of pretences: to erroneously confirm female virtue, police female bodies, behaviour and character. Olivia Millard explores the most recent shift in attitudes towards female bodily rights, as the Indonesian army announce an intention to end the practice of ‘virginity testing’

In early August this year, General Andika Perkasa announced that the Indonesian army would terminate mandatory “virginity testing” for female recruits. Such a statement signals progress for the longstanding global campaign against the practice but there is still a long way to go. It is unclear if and when the ban will be put into effect; the Indonesian police, navy and air force will still require negative results from these examinations, and apart from the inaccuracy and misinformation surrounding these tests, virginity testing continues to take place around the world, enforcing harmful stereotypes of female sexuality.

“ “The UN stated in 2018: virginity testing “has no scientific or clinical basis [...] can be detrimental to women’s and girls’ physical, psychological and social well-being.” ”

The so-called “two finger test,” has been used by the Indonesian army since 1965, but was only exposed in 2014 by Human Rights Watch. It was, and remains, condemned domestically and internationally as degrading, discriminatory and pseudoscientific. Under the guise of an “obstetrics and pregnancy test” as part of the recruitment medical, the test is performed to supposedly determine whether female applicants’ hymens are intact, based on the flawed belief that it can only be broken by intercourse. In an interview with The Guardian in 2015, a spokesman for the Indonesian military, Fuad Basya, stated: “We need to examine the mentality of these applicants. If they are no longer virgins, if they are naughty, it means their mentality is not good.” This reasoning is also used to justify the virginity testing of women marrying Indonesian military personnel, with virginity being seen as an important quality to ascertain a “good” future wife or female soldier. In a joint statement released in 2018, the World Health Organisation, UN Human Rights and UN Women called for a “collaborative response” to end the practice — which “has no scientific or clinical basis” and “can be detrimental to women’s and girls’ physical, psychological and social well-being.”

Not only is the test a traumatic and humiliating medical examination, it also indicates the concerning persistence of an archaic belief system which directly equates a woman’s value with her virginity. Societies have searched for a physical sign to determine virginity since time immemorial — it’s now known to be scientifically impossible. Despite this, virginity testing is still practised in at least 20 countries. Prisons and detention centres around the world, most notably in Egypt, India, Iran and Afghanistan, have also recently been exposed for conducting illicit virginity testing. In February this year, it was reported that many of the female student activists detained in Tehran for participating in peaceful protests against the Iranian regime were being subjected to virginity tests while in prison. In one particular instance, after resisting the examination, 21-year-old student Parisa Rafiei was sentenced to an extra 15 months in jail in addition to the seven years she is currently serving.

“the practice enforces the notion that sex outside marriage is only acceptable for men [...] and perpetuates the idea that female sexual activity should be held under public scrutiny”

In the US, rapper T.I. provoked a wave of public criticism in 2019 when he openly admitted on the Ladies Like Us podcast to taking his daughter to annual tests ensuring her virginity. Having acknowledged that the hymen can indeed be broken by activities such as horse-riding and riding a bike, he assured the interviewer that “she don’t ride no horses, she don’t ride no bike, she don’t play no sports,” stating that he considered the tests to be accurate. This demonstrates how the practice not only enforces the notion that sex outside marriage is only acceptable for men, but also perpetuates the idea that female sexual activity should be held under public scrutiny.

The UK is not exempt. In 1979 The Guardian exposed a so-called “gynaecological examination” carried out by immigration authorities on a 35-year old Indian teacher who had travelled to the UK to marry. Her status as an unmarried woman was doubted, and she was subjected to a virginity test. After a wide public outcry, the examinations were stopped, but the practice wasn’t totally eradicated. Only last year, the BBC discovered 21 clinics around the UK offering both virginity testing and “hymen-repair surgery”, an operation costing between £1,500 and £3000.

It remains to be seen whether there is meaning behind General Perkasa’s words; will the army really terminate the procedure? Needless to say, virginity testing is a global issue, spotlighting questions of female bodily autonomy, sexual health and women’s rights. The UK government has outlawed the process — certainly a step in the right direction — but in reality this move addresses only the tip of the iceberg. Long-lasting change can only come from fighting detrimental beliefs about female “purity”, a concept which intersects significant social, cultural and religious beliefs.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025