Withdrawal symptoms: the outcomes of foreign intervention in Afghanistan

An anonymous third-year student investigates what, if anything, can be pinpointed as having been to blame for the failure of NATO’s 20-year intervention in Afghanistan

In discussing the history of foreign intervention and the Taliban in Afghanistan, it pays to begin with the civil war that arose in the late 1970s following a bloody coup d’état staged by the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Despite strong support from the Soviet Union, the PDPA faced serious opposition from Islamic guerrillas, then funded by Pakistan and the United States.

An invasion by the Soviet Army in 1979 marked the start of the nine-year Soviet-Afghan War, resulting in openly armed civil defence groups and militias becoming commonplace in Afghan society. When the Soviets finally withdrew, the unstable coalition government that was left behind was quickly driven out by a newly-emerged militia – the Taliban. The harsh interpretation of Islamic sharia law enforced by the Taliban made life under their rule brutal, especially for women.

“Foreign intervention was supported by a majority of Afghans.”

However, it was not their human rights infractions that led to the subsequent intervention by the US in 2001. The American mission objective was to remove the Taliban from power, motivated by the Taliban’s provision of refuge and training grounds to al-Qaeda and their alleged refusal to hand over Osama Bin Laden. Foreign intervention was supported by a majority of Afghans.

Once the Taliban had been deposed, the new Afghan government needed security to exert its authority and begin, with foreign assistance, to rebuild the country. The UN Security Council established the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to maintain security and train the Afghan security forces until they were able to take responsibility for the country’s security themselves.

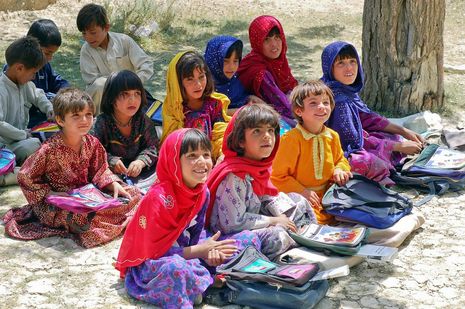

Vast security improvements paved the way for better governance and greater socioeconomic development. Afghanistan’s economy grew exponentially and significant progress was made in healthcare, education, and agriculture. The Afghan people were able to enjoy unprecedented civil liberties. The quality of life for women remained among the lowest in the world, particularly in rural areas. But even here, slow progress was made: women gained the rights to sit in parliament, to drive, to participate in international events like the Olympic Games; and many more.

Despite the social development of Afghanistan, the result of two decades of foreign intervention is a state of withdrawal. The process of permanently extracting NATO troops from Afghanistan began in February 2020 with the signing of the Doha Agreement. The US was understandably keen to bring an end to its decades-long involvement in Afghanistan; the conflict took a vast human and financial toll, with 2,461 US servicepeople losing their lives and thousands more suffering life-changing injuries and mental wounds.

But we must now ask the question: what was it all for?

President Joe Biden has stood by his claim that the US achieved its primary objective: to ensure that Afghanistan is no longer used as a base for launching terrorist attacks against America. He may be correct for the time being, but as the Taliban continues to welcome former al-Qaeda members into its leadership, there is little evidence to suggest this will hold true. From the moment the Doha Agreement was signed, the Taliban breached its conditions, launching a relentless series of offensives against the Afghan security forces.

“There comes a point when a country must deal with its own problems – foreign intervention has its limits.”

In spite of this, it seems no one predicted the speed with which the Taliban captured Kabul. Further surprise came from the overwhelming lack of resistance from the Afghan security forces, despite the billions of dollars they had received from NATO; the Taliban walked into Kabul.

If the intention was to keep the Taliban out of power, then the withdrawal should have been delayed. Yet, the Taliban made clear that the consequence of an extended occupation through the postponement (until September 11) of the original withdrawal deadline would be an increase in civil violence and the direct targeting of NATO troops. Rather than returning or delaying, was it not preferable to step back, hold up our hands, and say “we tried″? Not that this is what the United States is doing, hiding behind its smokescreen of ‘initial objectives.' There comes a point when a country must deal with its own problems – foreign intervention has its limits.

Analysis of the conflict in the coming months and years will seek to cast light on who should hold what proportion of the ‘blame,’ or at least, accountability. An incomprehensibly large sum of money was spent by NATO and its allies to develop Afghanistan. What do they have to show for it now the Taliban are back in charge? Does the blame for this failure fall upon the inefficiencies of the NATO intervention, led by the US? Or should we hold Afghanistan responsible for its own failings?

More likely, we cannot conclusively point the finger at any one reason.

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026