How social media challenged Compulsory Heterosexuality and gave lesbians a fresh start

Carmen Mas Franco reflects on Adrienne Rich’s notion of Compulsory Heterosexuality, its erasure of queer lived-experiences and considers how Tiktok has helped queer and questioning youth challenge heteronormativity

Content note: This article contains detailed discussions of homophobia and transphobia.

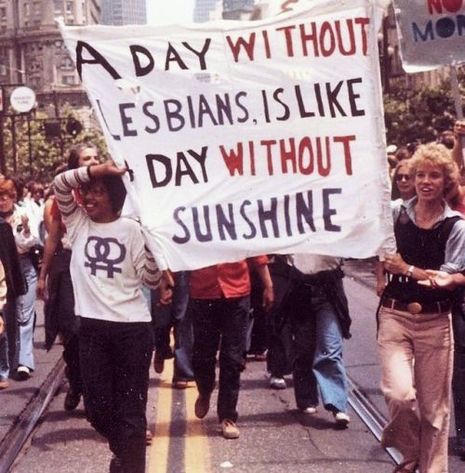

As lesbian liberationism gained traction in the late seventies, essayist Adrienne Rich published what quickly became a foundational text for gender and queer studies. Rich’s “Compulsory heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” initially cautioned modern feminism against upholding the edifice of heterosexuality. Today, her seminal essay is undergoing a revival driven by the period of self-reflection that lockdown entailed for queer and questioning youth. Mediated through Tiktok’s incredibly precise algorithm and the dissemination of collaborative documents online, Rich’s observation of compulsory heterosexuality (Comphet) has become the latest buzzword in virtual queer circles, allowing many individuals to find clarity. As a relatively late-blooming lesbian, I am grateful that Comphet is being dissected through social media discussions, but I argue these conversations must become mainstream to be truly emancipatory.

Originally, Rich’s 1980 essay rejected the liberal tendencies towards individualism that had existed within queer activism and feminism. During the 1950s and early 1960s, most North American LGBTQ+ associations saw homophobic interactions as punctual acts of prejudice that could be undone through bettered education. This trend was dramatically reversed in the following decades, when an outburst of freedom movements for racial, gender and sexual minorities popularised the denunciation of homophobia as a systemic issue. In this climate, Rich considered heterosexuality to be a political institution sustained by two pillars: women’s assumed orientation towards men and the neglect of lesbian existence that follows from the former. For her, the history of women who challenged the heterosexual order — as lesbians, “marriage resisters,” and aligning with other women — was neglected at a high cost. This lesbian and queer erasure permeated social culture and media narratives over the subsequent decades; take the gay best friend cliche and queer characters, particularly lesbians, being killed off in storylines as examples of the harmful “Bury Your Gays” trope. Messages of default heterosexuality and the vilification of queerness pervade our lives as we are assumed to be straight, unless proven otherwise. For instance, when I was just nine years old I promised myself I would never admit to two things: firstly, the fact that I couldn’t ride a bike, and secondly that I was attracted to girls. My internalised adherence to Comphet caused me to become an expert in repressing my feelings, so much so that when I walked into university I identified as straight. My personal journey in recognising the effects of Comphet displays how the solidity of the assumption of default heterosexuality — through social norms, narratives — makes the act of refuting it especially challenging and guilt-ridden.

“Many were able to access a virtual space that was relatively free from the tentacles of heteronormativity for the first time ever”

For this reason, I am appreciative that Comphet and its effects have been increasingly scrutinised on social media, particularly during the first months of the Covid pandemic. Worldwide web searches of “Compulsory Heterosexuality” from 2004 on Google Trends, peaked from July to August 2020. Similarly, there was an exponential increase in searches for “Comphet” ranging from March 2020 to August 2021. Together with Twitter, Tiktok became the platform through which critiques of Comphet were made readily available, its app installations increasing 34% during the week of the 23rd of March 2020. By monitoring user interaction in the form of likes, comments, follows, watch-time and skipped videos, the Tiktok algorithm was able to create Feeds that were solely or mostly comprised of content made by queer creators for more or less “out” queer audiences. The great specificity of the app’s Feed meant that many were able to access a virtual space that was relatively free from the tentacles of heteronormativity for the first time ever. Higher exposure to LGBTQ+ content and the interruption of routine led to an intense period of reflection for newly questioning youth. Rich’s notion of compulsory heterosexuality was gaining relevance with every share.

I found that most Tiktok videos and Twitter threads summarising compulsory heterosexuality referenced Angeli Luz’s “Am I a Lesbian?”. This text, initially posted on Tumblr, became a viral summary of the ways in which women and non-binary people can recognise Comphet to “do some soul searching and figure out our consciousness” and sexual identity. Although there’s no explicit mention of Rich, it contains an explanation of compulsory heterosexuality, as well as different prompts and questions that may help curious individuals clarify their preferences. From this, statements such as “lesbians are allowed to like male fictional characters” or “you can identify as a lesbian if you’ve liked men in the past but no longer are attracted to them” have now become popular online.

“Rich’s figure and legacy are confusing and hurtful for many gender non-conforming, non-binary or trans lesbian and queer individuals”

However, the popularisation and increasing awareness of Comphet hasn’t happened without an understanding of Rich’s more condemnable behaviours. Adrienne Rich counselled Janice Raymond in her writing of her deeply transphobic work “The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male,” a book which often confounds sex with gender and issues hurtful declarations against transgender women such as accusing them of colonising “feminist identification, culture, politics, and sexuality.” Thanked in the forward of Raymond’s book, Rich’s figure and legacy are confusing and hurtful for many gender non-conforming, non-binary or trans lesbian and queer individuals. Taking into account Rich’s problematic contributions, the rearticulation of her ideas through social media has proven to be a safer and more inclusive medium for their circulation.

It’s true Rich’s text promotes a binary understanding of gender — a recognisable shortcoming. Nevertheless, compulsory heterosexuality and its “denials of feeling” need to be addressed in queer culture as it’s vital to shed light on the psychological trappings that keep many lesbians locked away from self-definition and caged within the acceptable. Like many others, only through an online exploration of Comphet was I able to adopt the lesbian label and reconcile my reality with the fact that I felt obligated to date men in the past. While I am grateful for having had the privilege to access discussions of sexuality when I needed it most, I find it disappointing that queer individuals of all ages must still resort to virtual spaces to explore their identities. Heteronormative society needs to do better. Fighting against homophobic and transphobic beliefs is no small feat, but dismantling default heterosexuality and considering queerness as a possibility during a child’s formative years may be a good place to start. Similarly, supporting diverse LGBTQ+ political and cultural representation, pushing for educational reform, or advocating for the protection and funding of marginalised queer voices are other important ways in which we can change what mainstream means for the better.

It is impossible to tell if Rich, who died in 2012, would have expected “Comphet” to become a popular term used by lesbians to address their struggles with false consciousness. Her 1980 essay included a passage by Kathleen Barry explaining the importance of “naming” different forms of repression in order to define the lived experiences of their victims. Forty years after the publishing of "Compulsory Heterosexuality," we can confidently say that the theory has become Name. Now the onus is on us to ensure these valuable discussions are destigmatised and brought into the mainstream. As written by C. Green on childhoods spent in the closet:

“The signs were there, but when you don’t know where you’re going […] the signs don’t mean anything.” And so, we thank Compulsory Heterosexuality, challenged and refashioned through the democratising forces of the internet, for showing us the way. Still, only time will tell if this resurgence is effective.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026